20 Selected Stories From the Exhibition

All Items

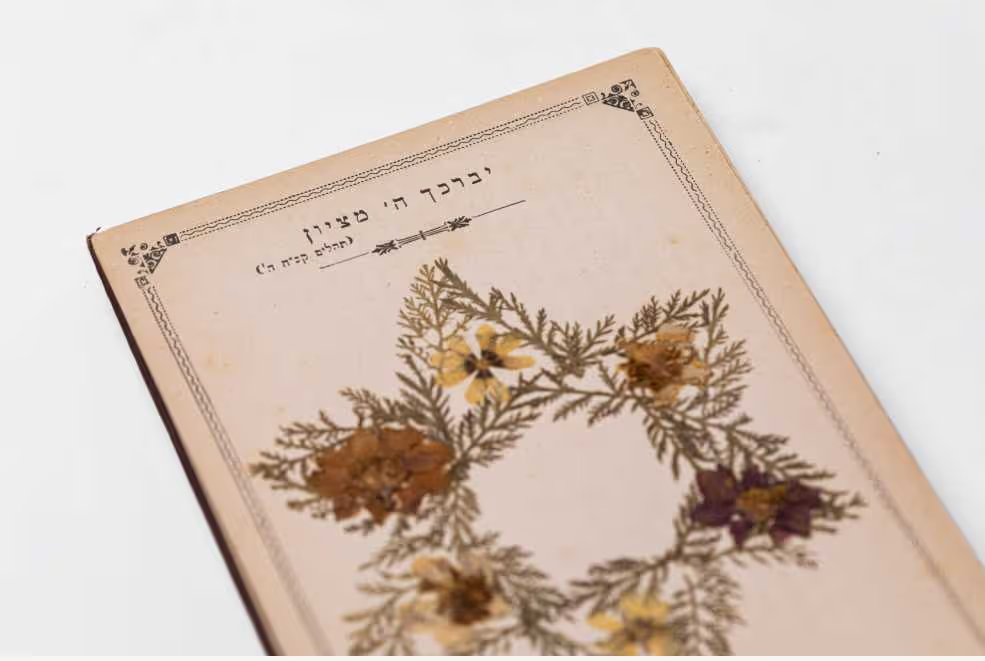

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, albums of dried flowers from the Holy Land were a souvenir in high demand by tourists and pilgrims, both Christian and Jewish. The album displayed here has in addition colored illustrations of the holy places. The flowers selected are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, and gathering them together created a direct connection between the actual Land of Israel and descriptions of it in Scripture.

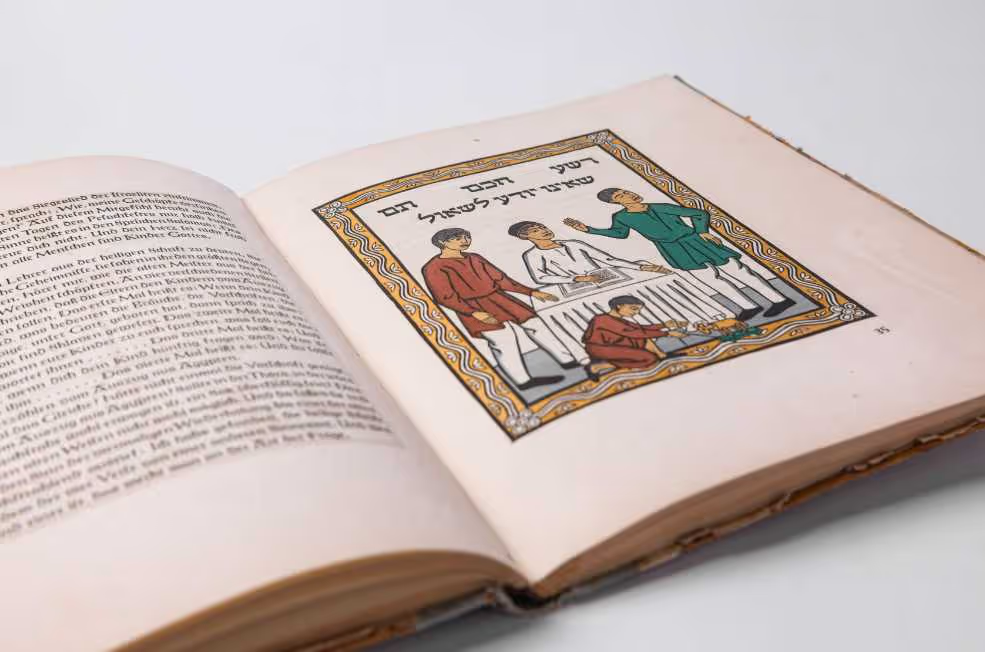

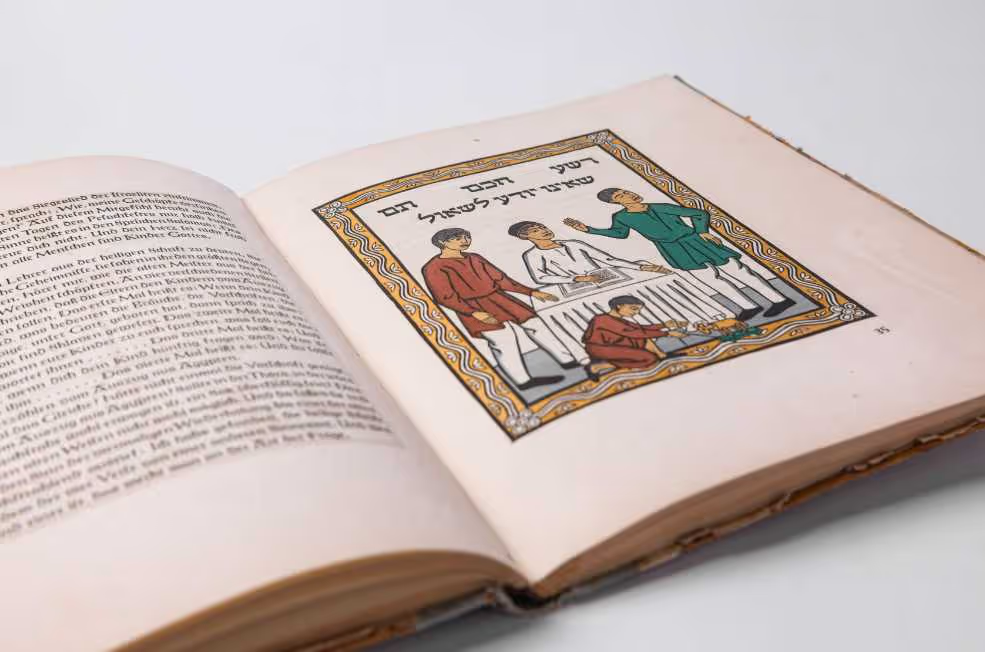

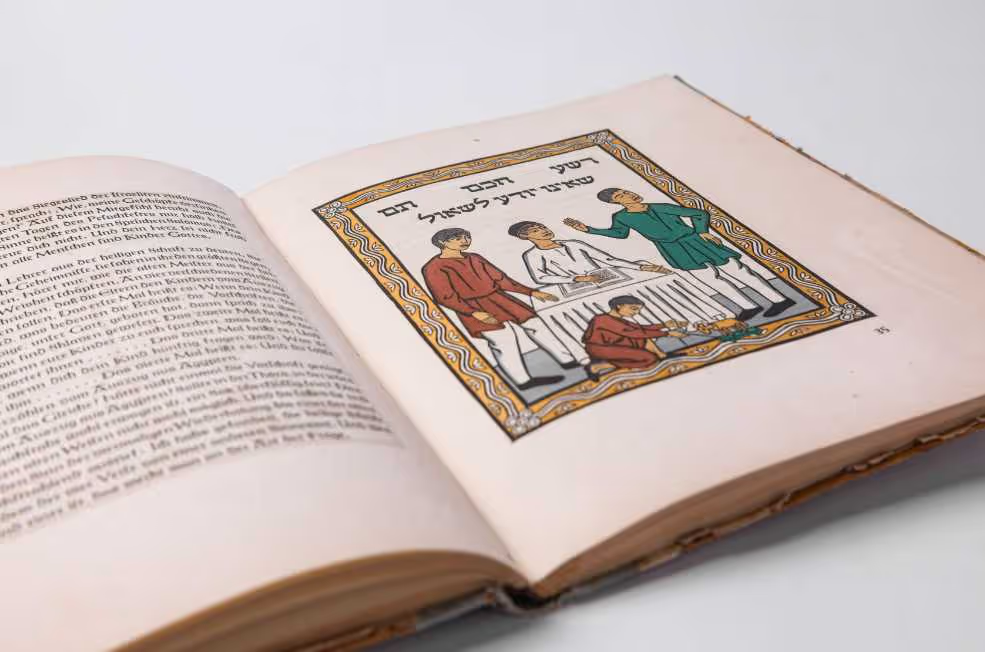

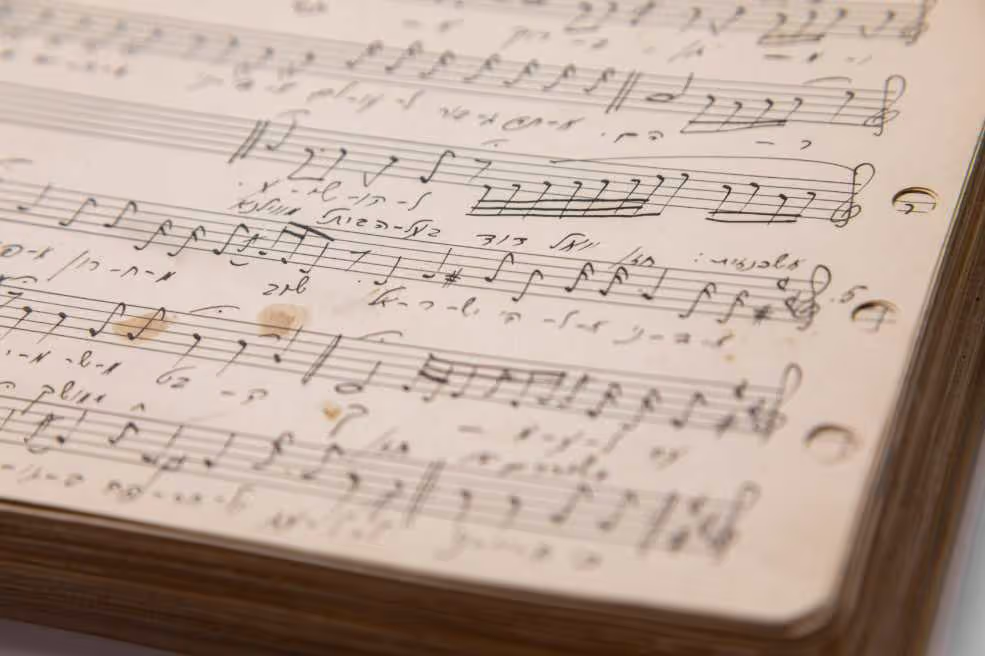

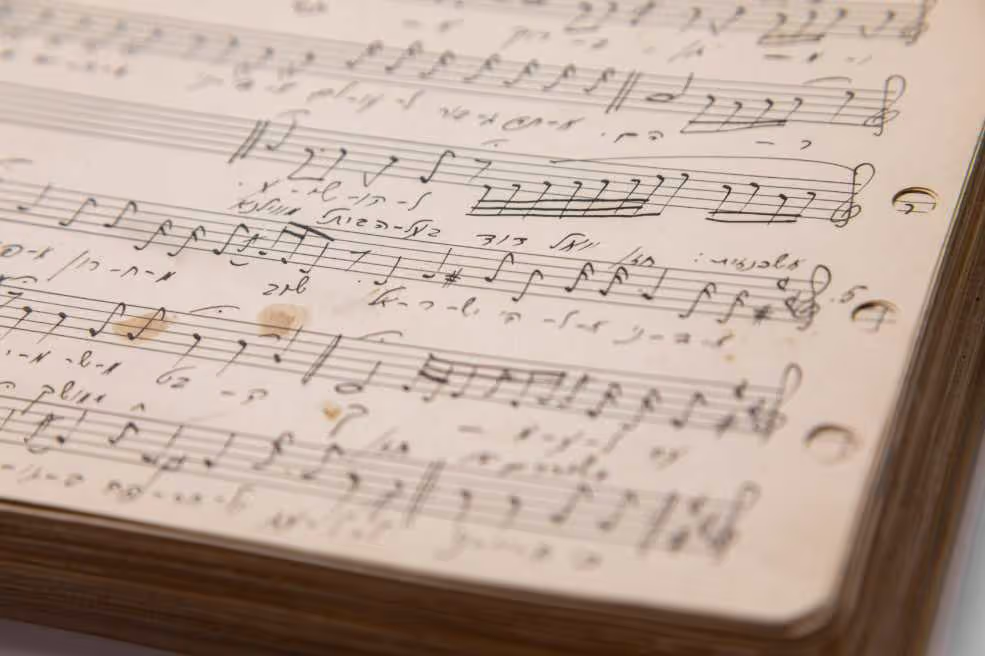

This Reform Haggadah is in German, with extracts from the Hebrew original in transliteration to assist participants unable to read Hebrew. The commentaries combine traditional and liberal approaches, and the text is decorated with hand-painted images, and songs with musical notation. The font was created specifically for this Haggadah, and was commissioned by the publisher, Siegfried Guggenheim. Guggenheim, born in Worms, Germany, initiated the publication of this special format of the Haggadah to connect the younger generation of his family to Jewish tradition. The Haggadah closes with the surprising prayer “Next year in Worms am Main, our home,” showing German Jews’ deep connection to their country.

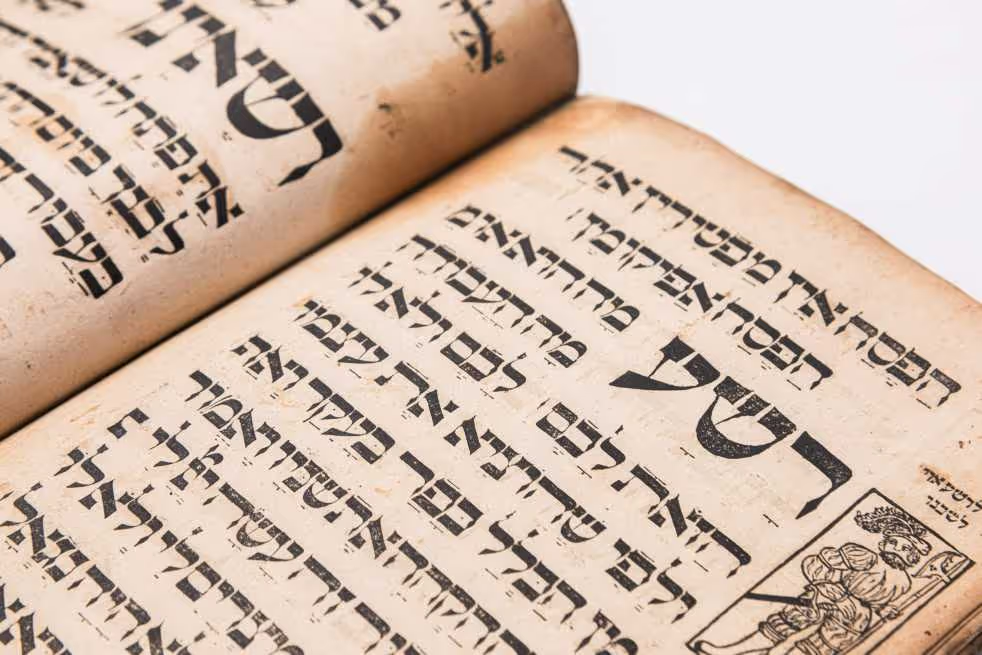

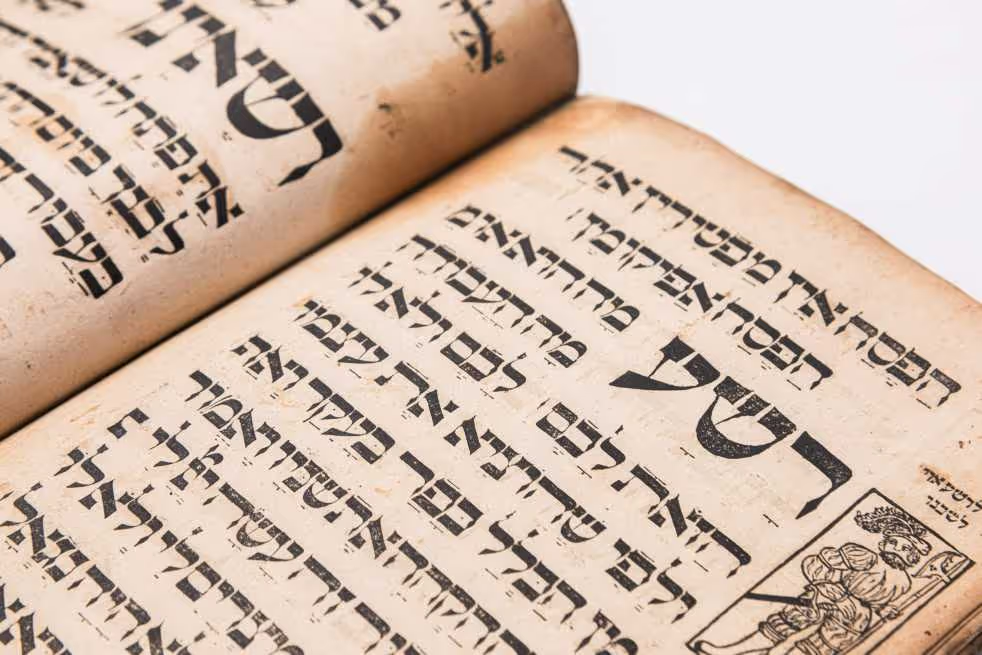

This is the only surviving copy of the first Haggadah ever printed, a few years before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. It shows the high standard of printing by Spanish Jews. After the expulsion, the Jews took the technology to the countries where they found refuge, in Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

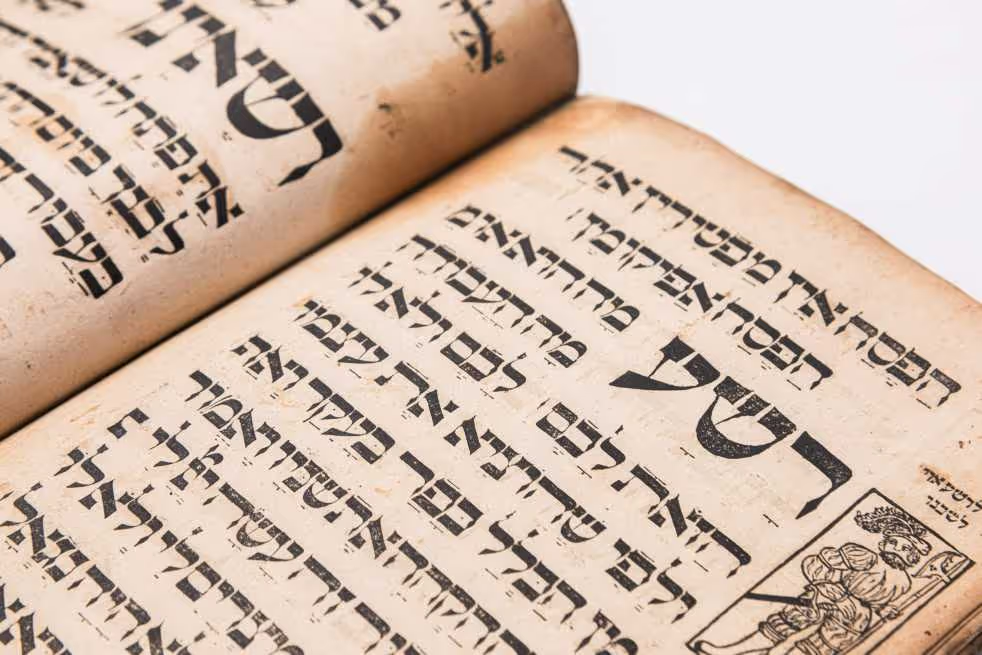

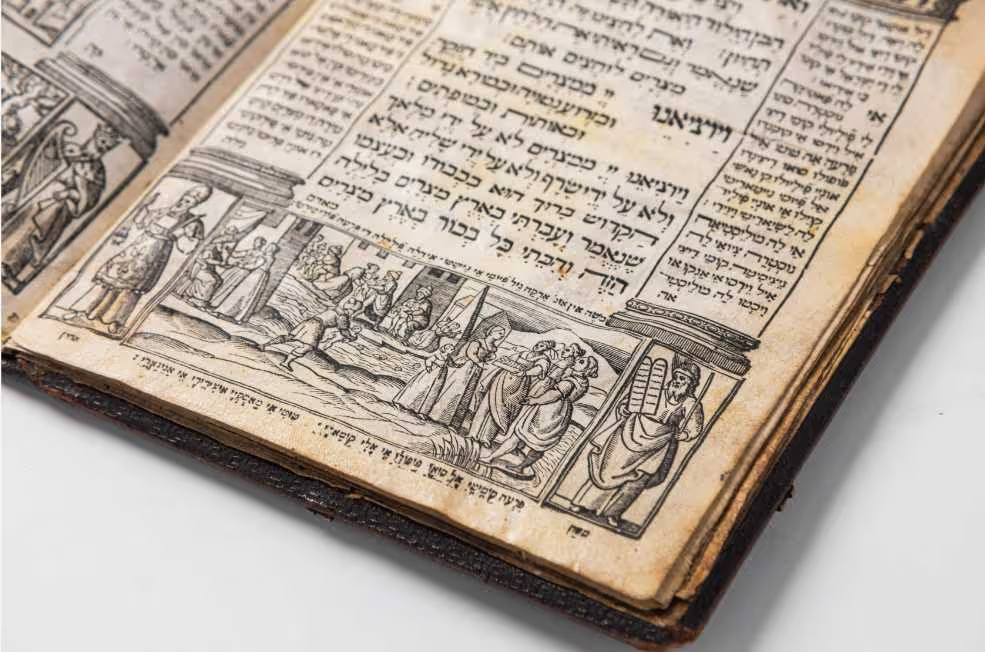

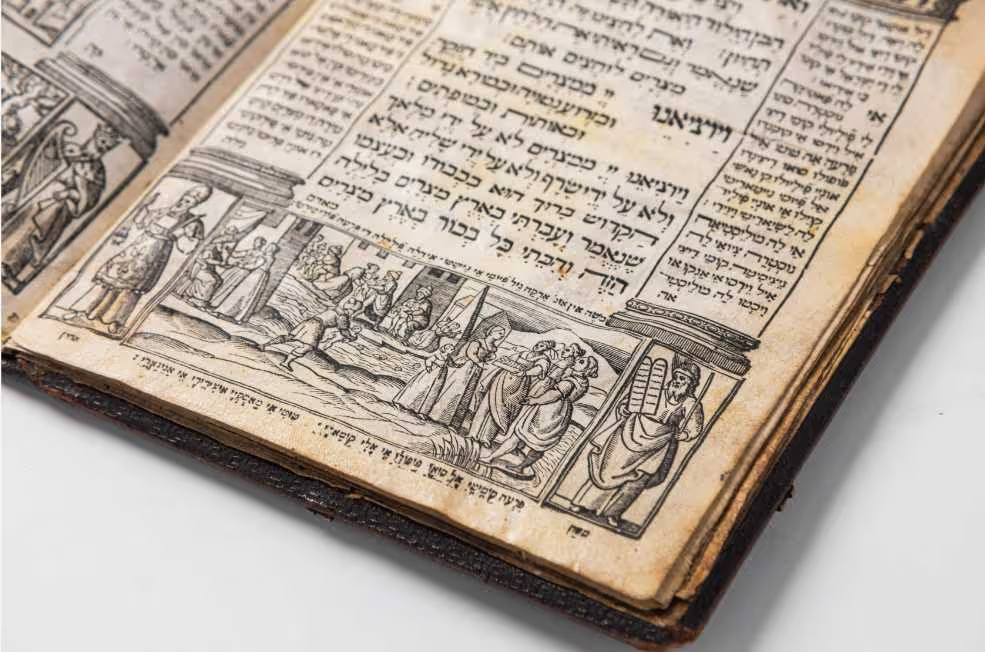

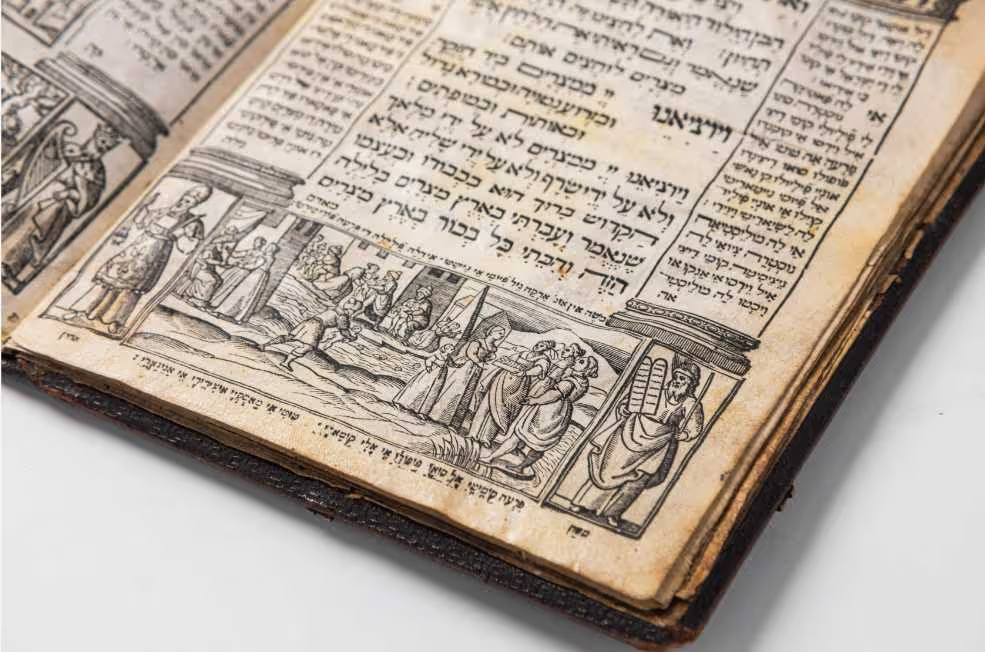

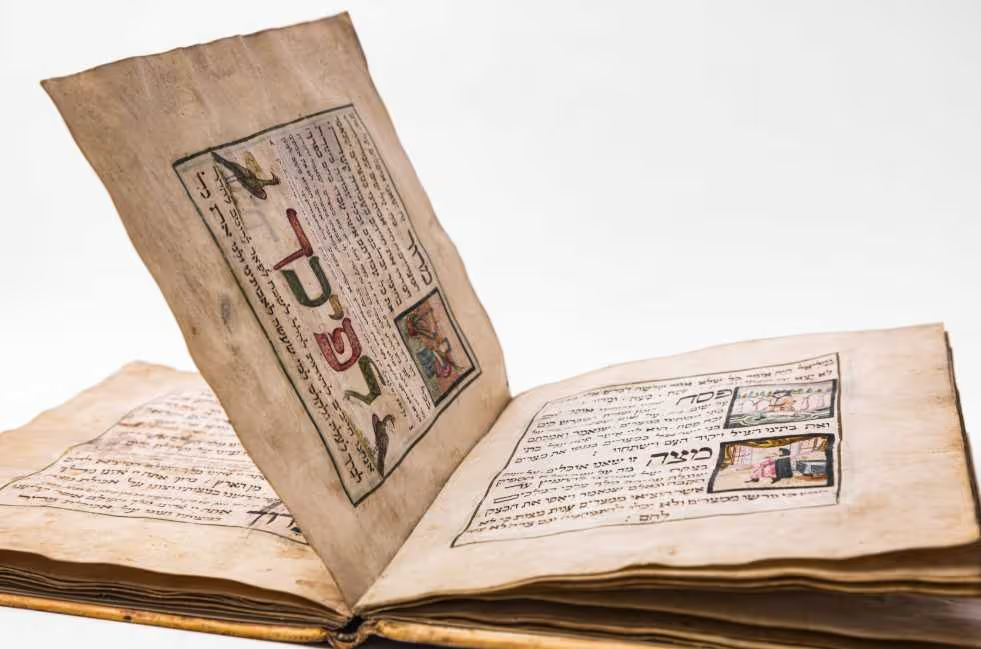

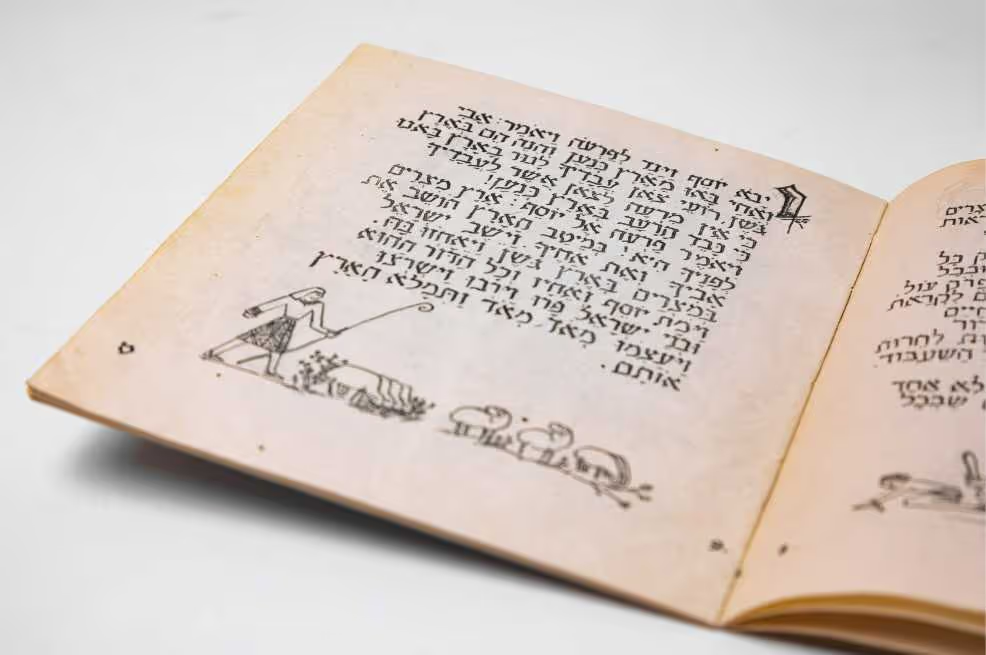

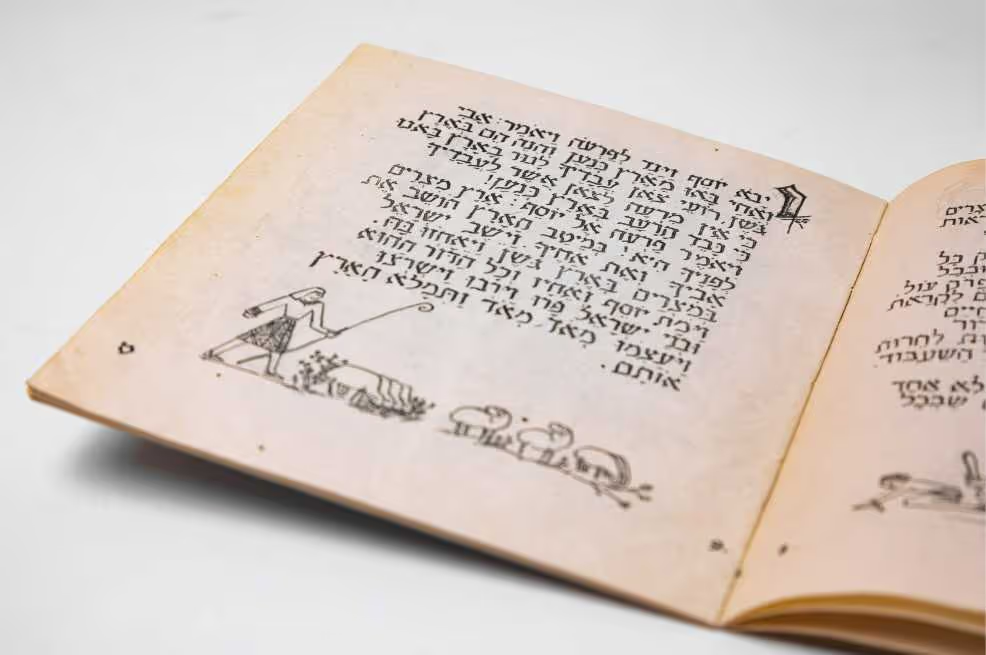

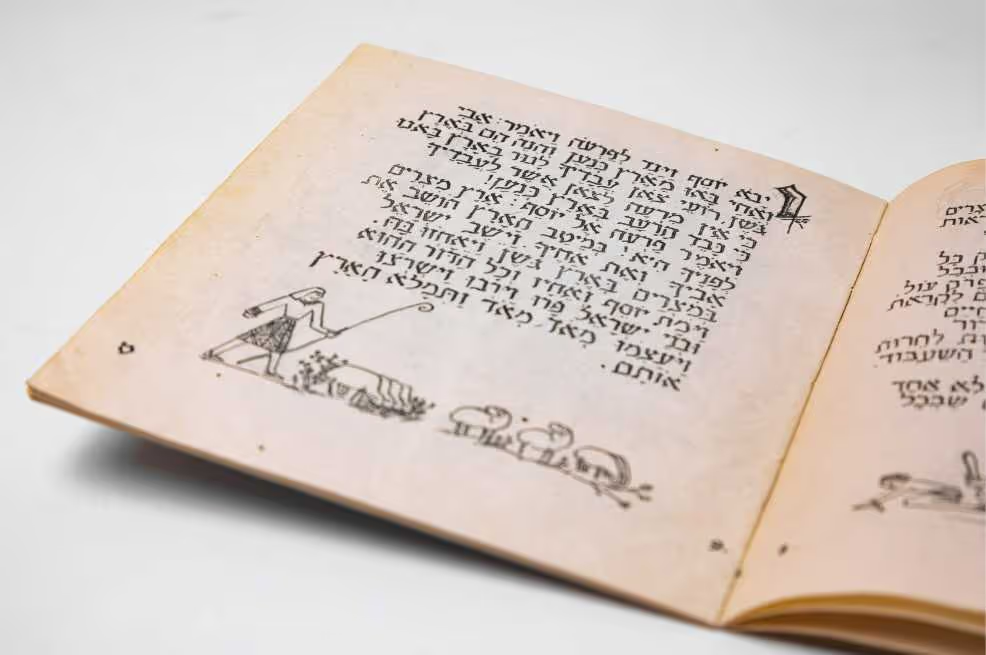

This pioneering masterpiece is the first complete illustrated printed Haggadah that survived in its entirety. The format and the illustrations were a source of inspiration for later printed Haggadot. The woodcut technique allowed design innovations including reuse of visual elements in order to reduce work for the artist, integrated design of the page layout and the book as a whole, and use of images to symbolize concepts. The balance and harmony between text and illustrations is attributable to these innovations.

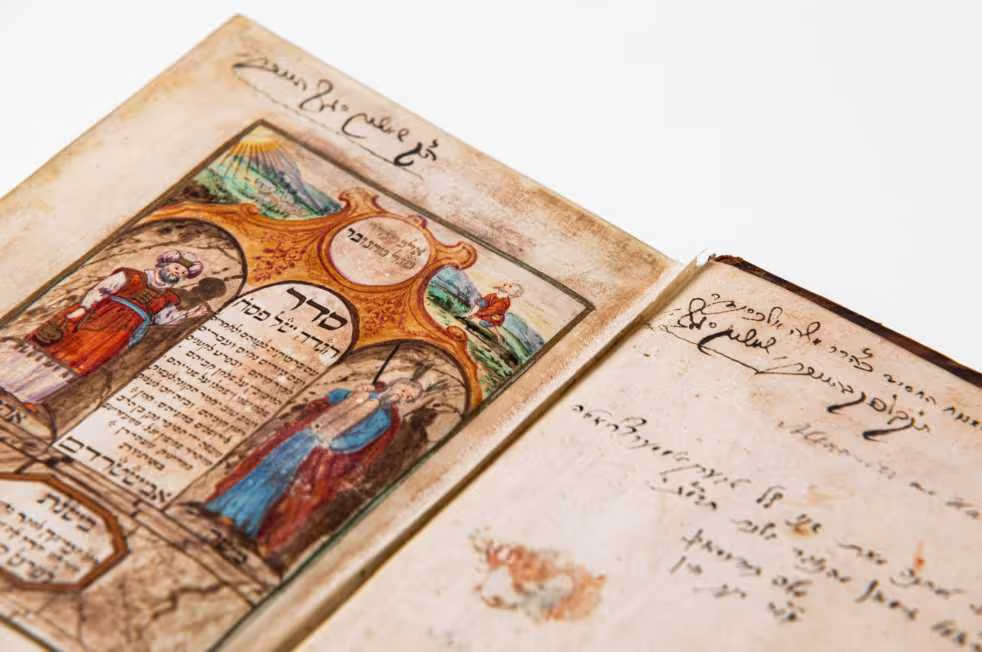

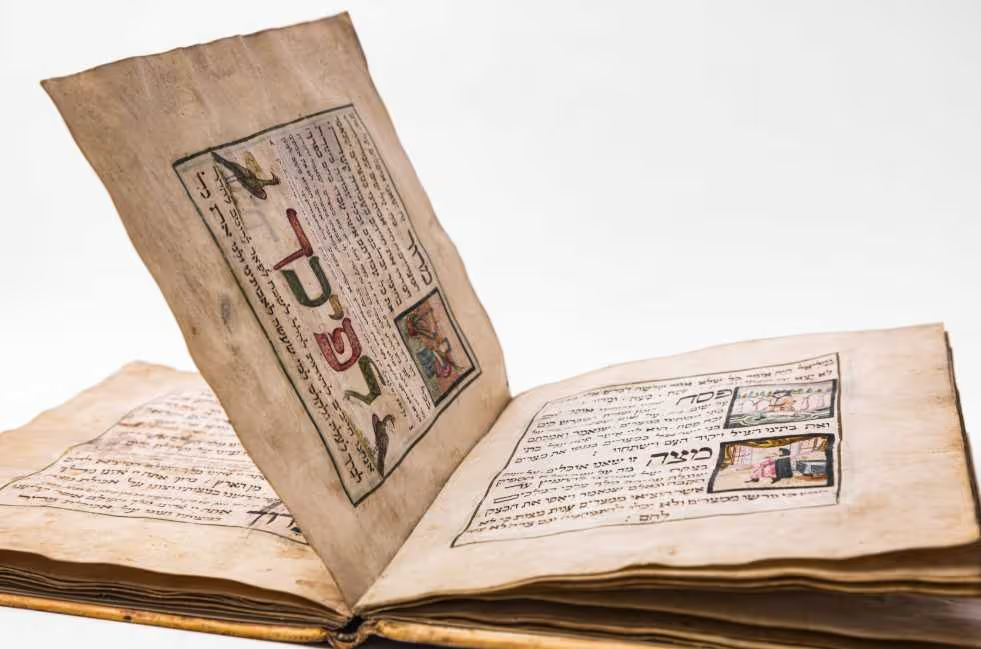

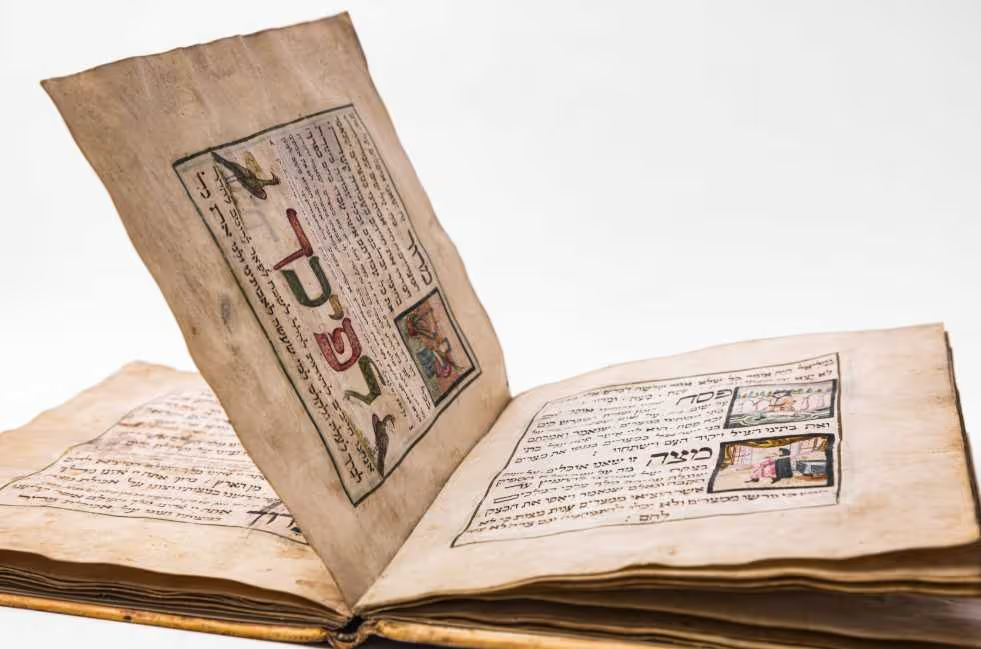

The illustrations in this Haggadah, created by engraving on copper plate, were much loved and were used as the basis of many printed Haggadot up to the present day. Among the evidence for its great success are hand written and illustrated 18th-century Haggadot imitating its illustrations and fonts. The “Amsterdam Haggadah” was also the first Haggadah to include a printed Hebrew map of the wanderings in the desert, inspired by the work of the noted 16th-century cartographer, Christian van Adrichem.

This Haggadah with Italian translation is one of a group of three early printed and illustrated Haggadot, an outstanding achievement in the field of Haggadot with woodcut illustrations. Apart from the Italian translation, it was translated into Ladino and Yiddish as well, achieving a wide distribution in 17th-century Europe. The illustrations were incorporated into other Haggadot.

This Haggadah with Ladino translation is one of a group of three early printed and illustrated Haggadot, an outstanding achievement in the field of Haggadot with woodcut illustrations. Apart from the Ladino translation, it was translated into Italian and Yiddish as well, achieving a wide distribution in 17th-century Europe. The illustrations were incorporated into other Haggadot.

The illustrations in this Haggadah were influenced by the copper engravings in Haggadot published in Amsterdam, such as the one exhibited nearby. The illustrator, Yosef ben David, was active in Germany. Apart from this Haggadah, six others are known to be his work during a 10-year period.

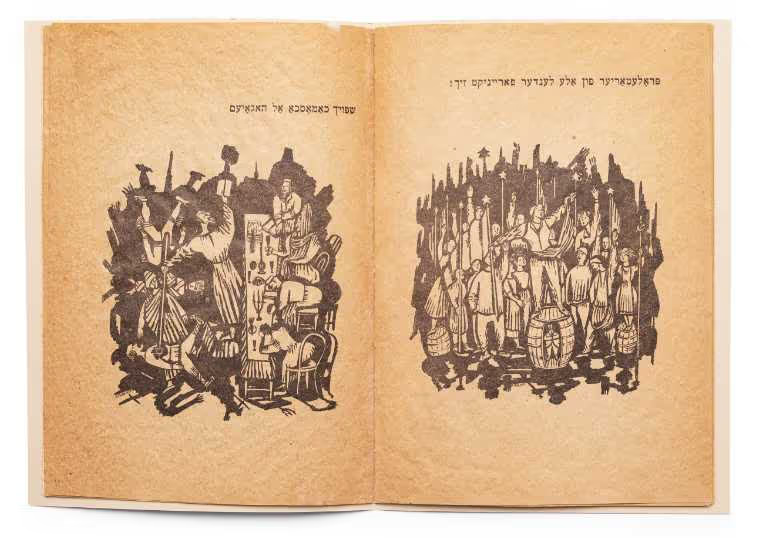

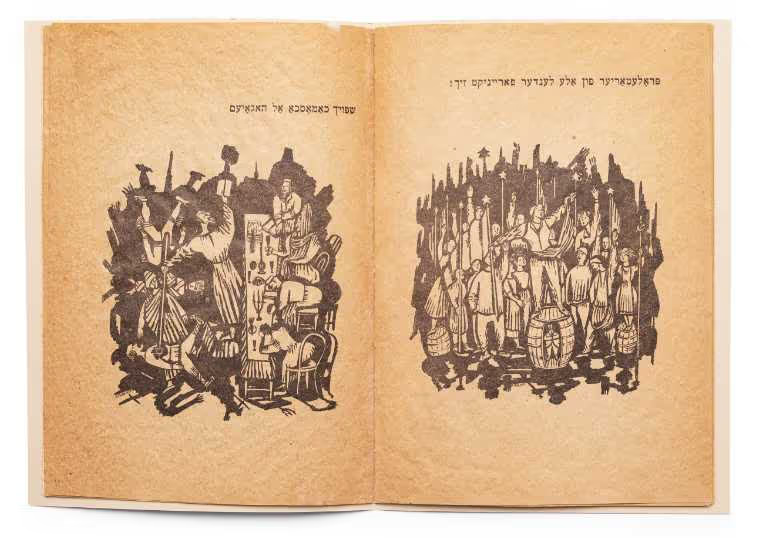

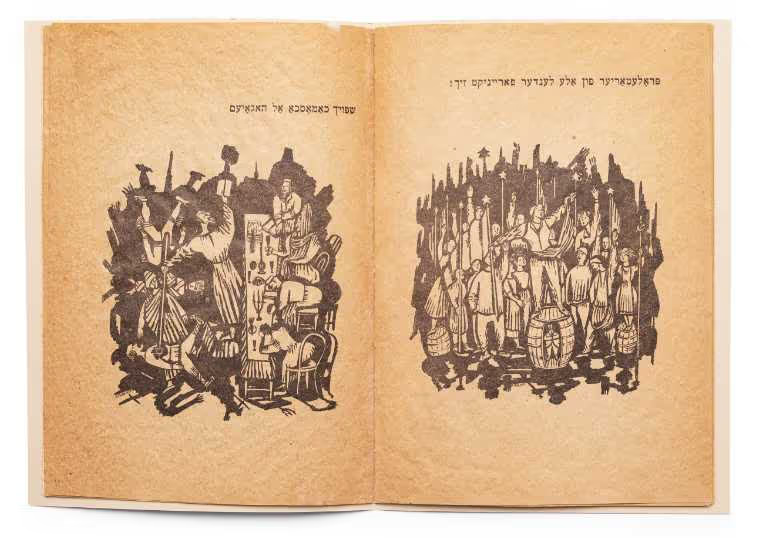

A Haggadah written in Yiddish and illustrated by Moshe Altshuler in 1922 as a contribution to the dissemination of Communist Party ideology. The author adapted the concepts of the Haggadah and interpreted them in the spirit of the Russian Revolution. For example, he used the description of “destroying leaven” to illustrate the USSR destroying the bourgeois leaven remaining in Russia: house owners, merchants, and exploiters of the proletariat. The Haggadah ends with the call: “This year revolution here – next year world-wide revolution!”

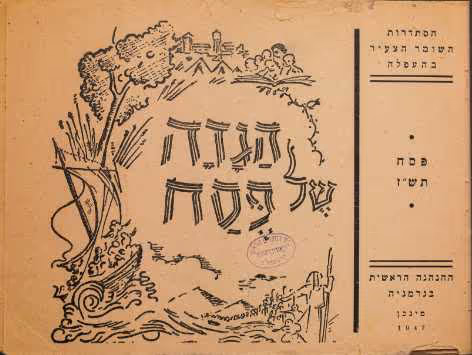

In the Haggadah exhibited here, the answer to the question “Why is this night different from all other nights” is “because we are celebrating this Seder night on the way to our homeland, while the gates to the Land of Israel are still locked.” The answer is relevant to the participants at Seder night in Displaced Persons’ camps: thousands of Holocaust survivors uprooted from their former lives in Europe, on their way to the Land of Israel.

The “escape” movement organized by underground groups and partisans from 1944–1948 was led by the Zionist pioneer movements, chief among them Hashomer Hatzair.

The 179th Company was one of the Jewish volunteer companies in the British Army at the beginning of World War II. The Haggadah exhibited here was printed in Italy one month before the victory over Germany, after the liberation of the concentration camps and extermination camps. The additions to the canonical text convey the sensation of imminent liberation, with the desire for vengeance against Nazi Germany another prominent motif.

This Haggadah, prepared for soldiers of the pre-state underground militia, the Hagana, at the peak of the fighting in the War of Independence, stresses their role as successors of Jewish warriors from all periods, from the conquest of Canaan to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

The illustrator Arie Alweil made a connection between the historical narrative and contemporary events: the Second World War, the Holocaust and the ghetto uprisings, and the establishment of the State of Israel. Alweil was one of the few Israeli artists who created works related to the Holocaust at the very time it was happening.

This Haggadah was created for a Seder celebrated by soldiers of the Palmaḥ militia a few days after the heavy fighting for the fort at Nebi Yusha, in which 26 of their comrades were killed. The text alludes to the effects of the battle and the recognition of the fragility of the Jewish community’s existence just before the establishment of the state. The bereavement and loss in contrast with the willingness to lay down their lives for the cause of establishing the state, are ever-present themes. The Haggadah praises the heroism of the Palmaḥ’s soldiers throughout the country, and contrasts it with the bitter fate of the Jewish people in the Diaspora and the Holocaust.

Yehuda Sharett, a Russian-born composer and violinist, proposed a “new” Passover Seder in 1937 and created a kibbutz Haggadah based on the traditional text, with additional poems, a play and ballet, traditional melodies, familiar songs and new melodies of his own composition. This new Seder was a complete musical work that was later performed in concert halls. The Yagur Haggadah eventually became the standard Haggadah in many kibbutzim, and pages from it were incorporated in the pioneer movements’ Haggadot used in the Displaced Persons’ camps in Europe.

This Haggadah produced by the socialist Hashomer Hatzair movement was decorated and illustrated by Ruth Schloss, a member of the movement who later gained a reputation as a social protest artist. The experience of the Holocaust and current events in Israel and worldwide appear as reflections of the story of enslavement in Egypt and the Exodus, and were enlisted to promote social concepts such as the class struggle.

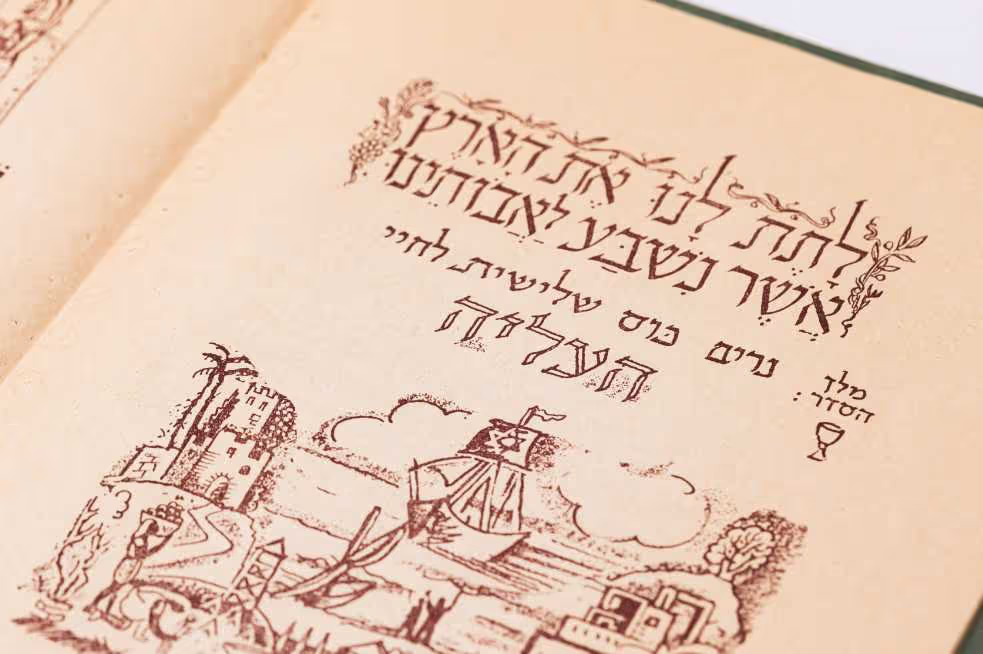

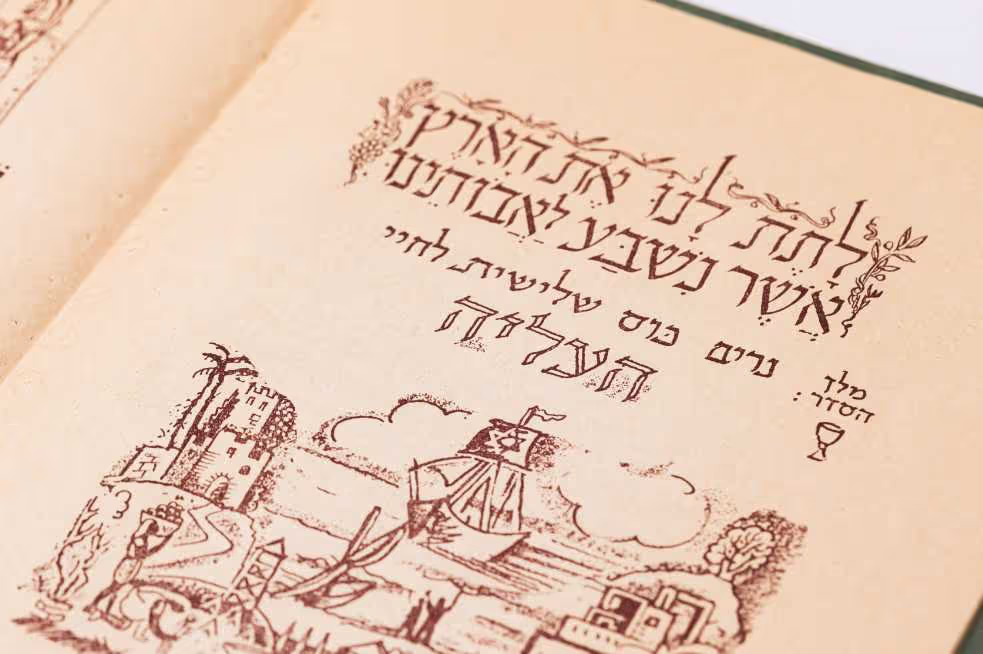

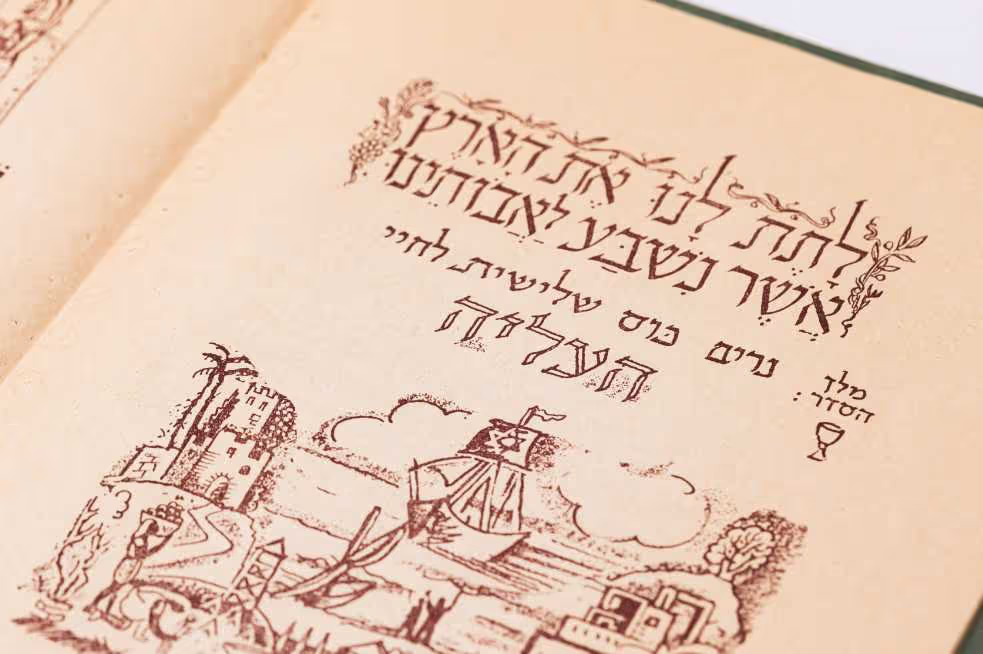

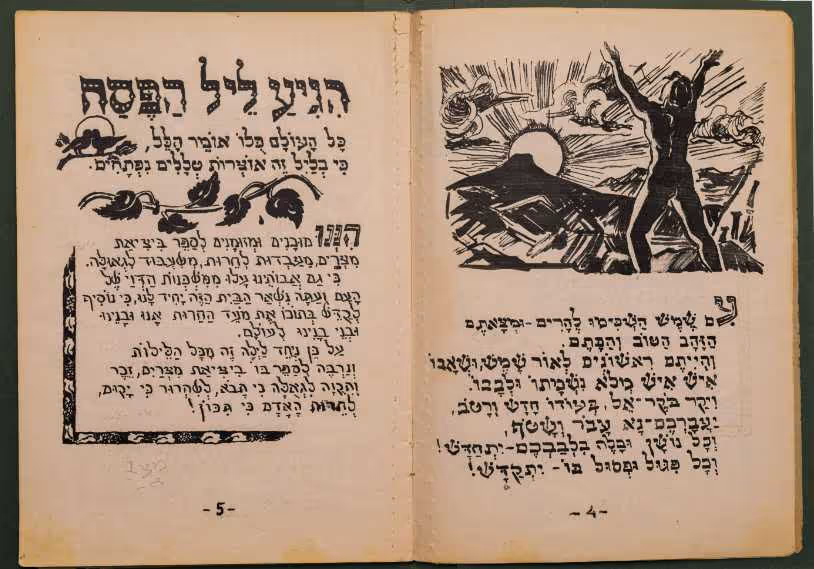

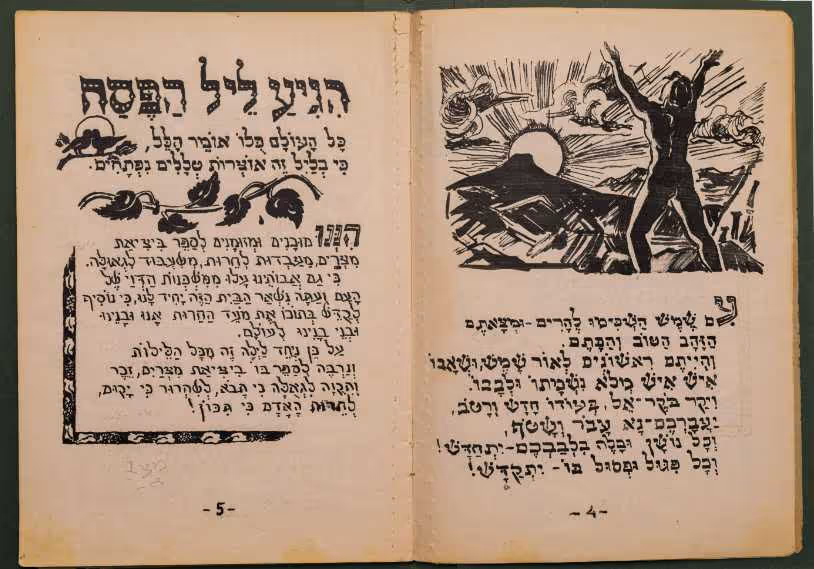

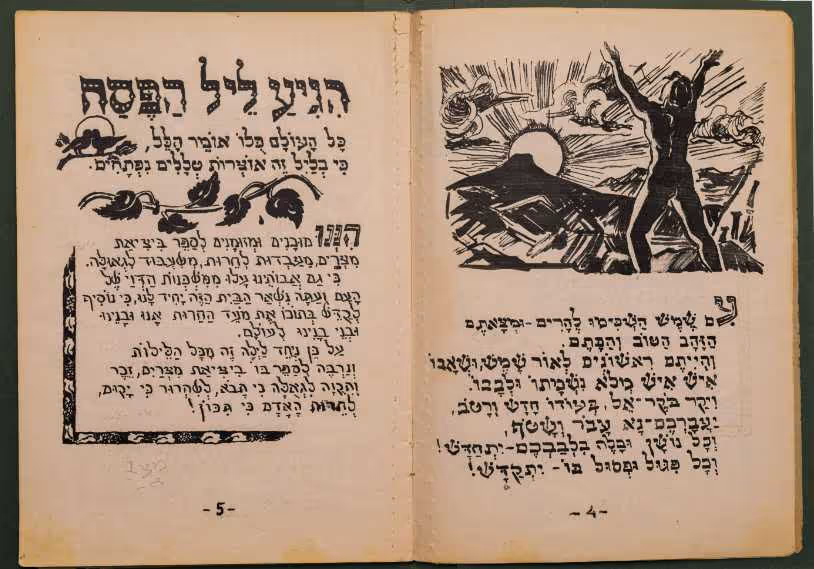

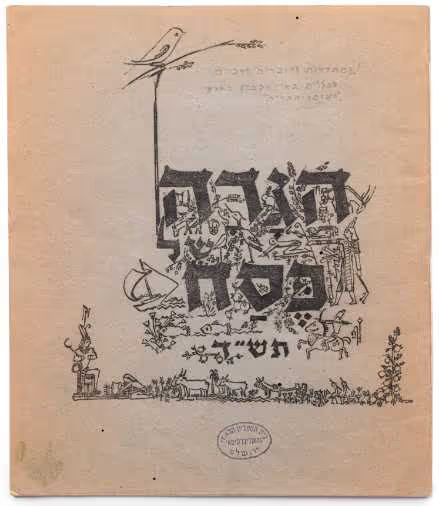

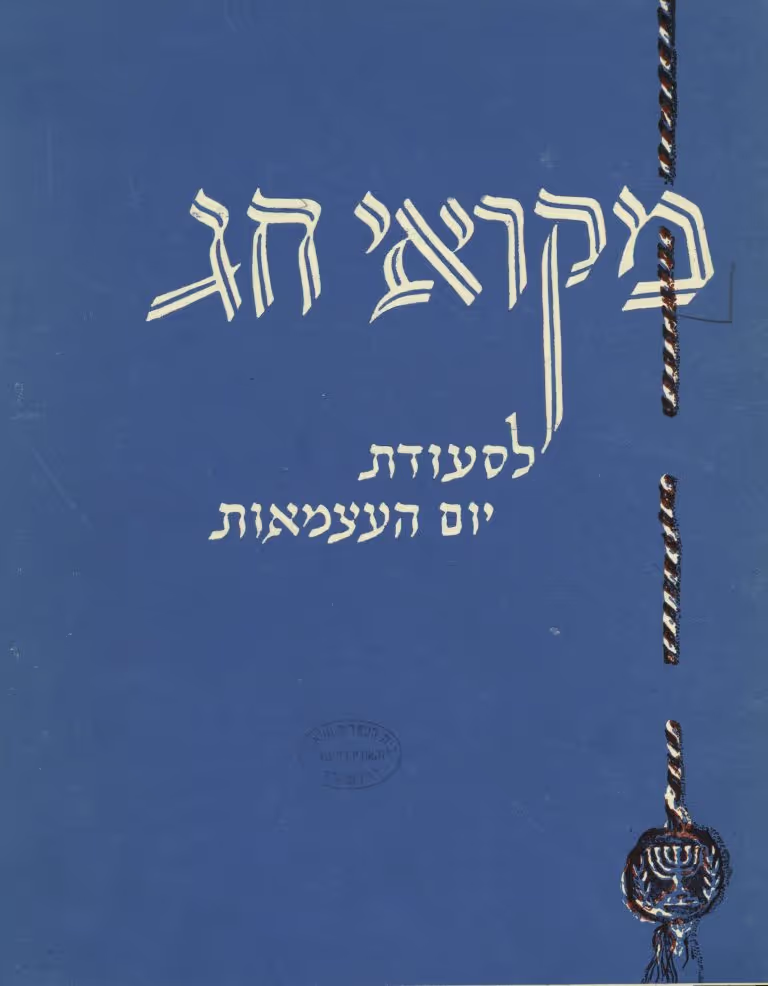

On Seder night the “Gaʿaton” work battalion (now known as Kibbutz Neot Mordechai) used one central, sumptuously decorated Haggadah, exhibited here. The Haggadah is evidence of the new young community’s desire to express its values and identity within the kibbutz movement. The hard work invested is visible in the editing of the content, with traditional themes seen through a contemporary lens, and in the illustrations and the varied design of the lettering.

On Seder night the “Gaʿaton” work battalion (now known as Kibbutz Neot Mordechai) used one central, sumptuously decorated Haggadah, exhibited here. The Haggadah is evidence of the new young community’s desire to express its values and identity within the kibbutz movement. The hard work invested is visible in the editing of the content, with traditional themes seen through a contemporary lens, and in the illustrations and the varied design of the lettering.

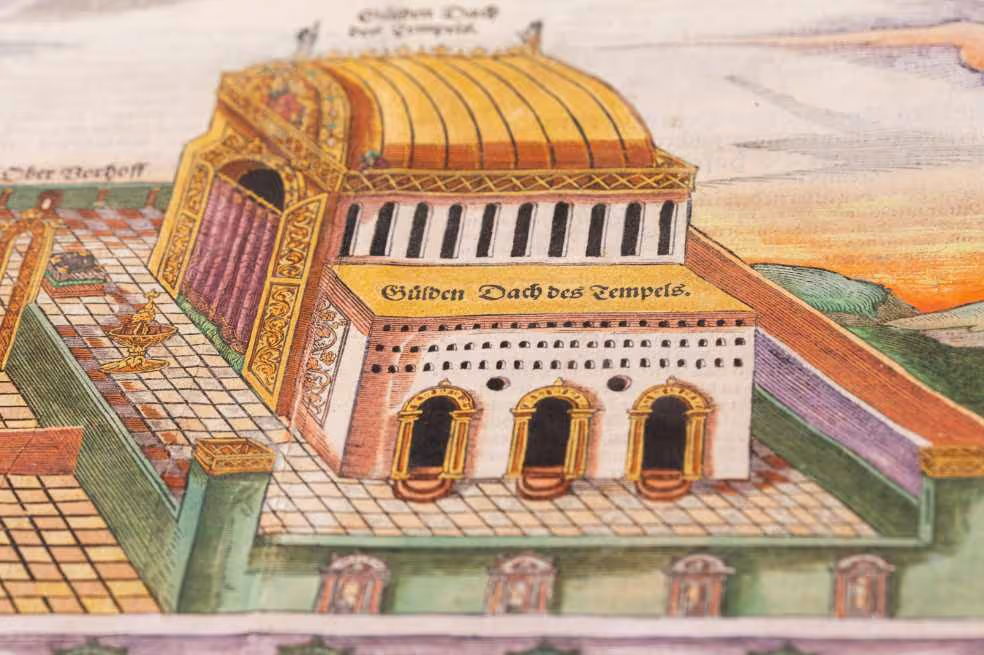

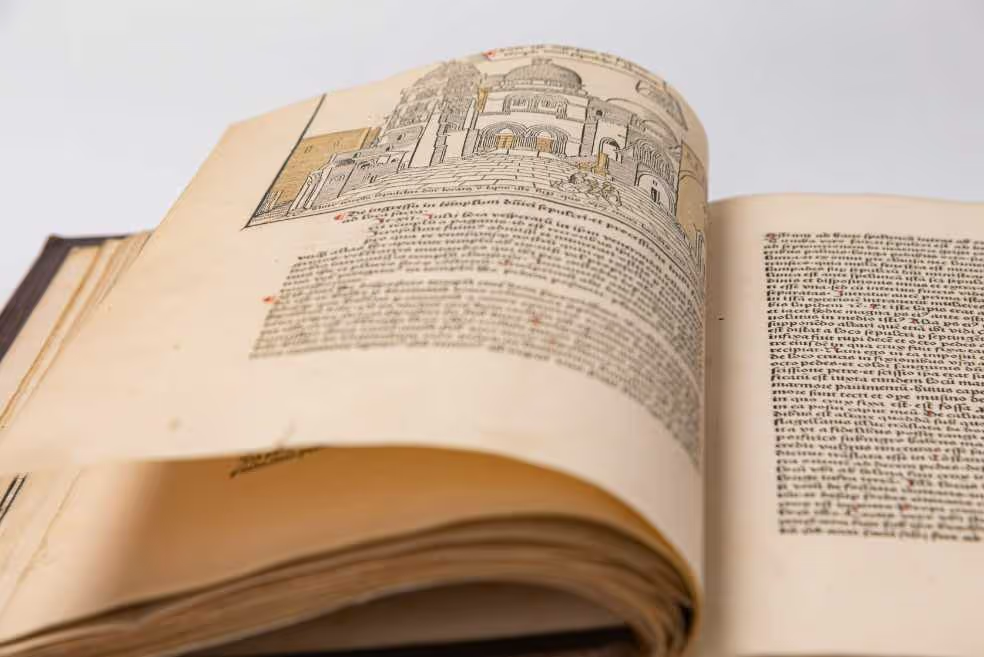

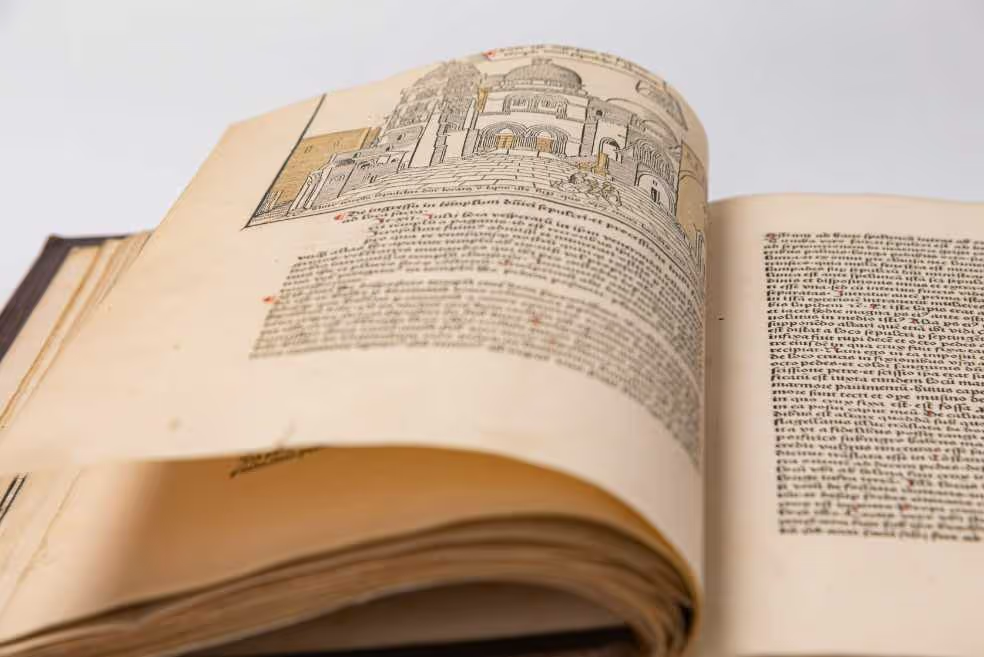

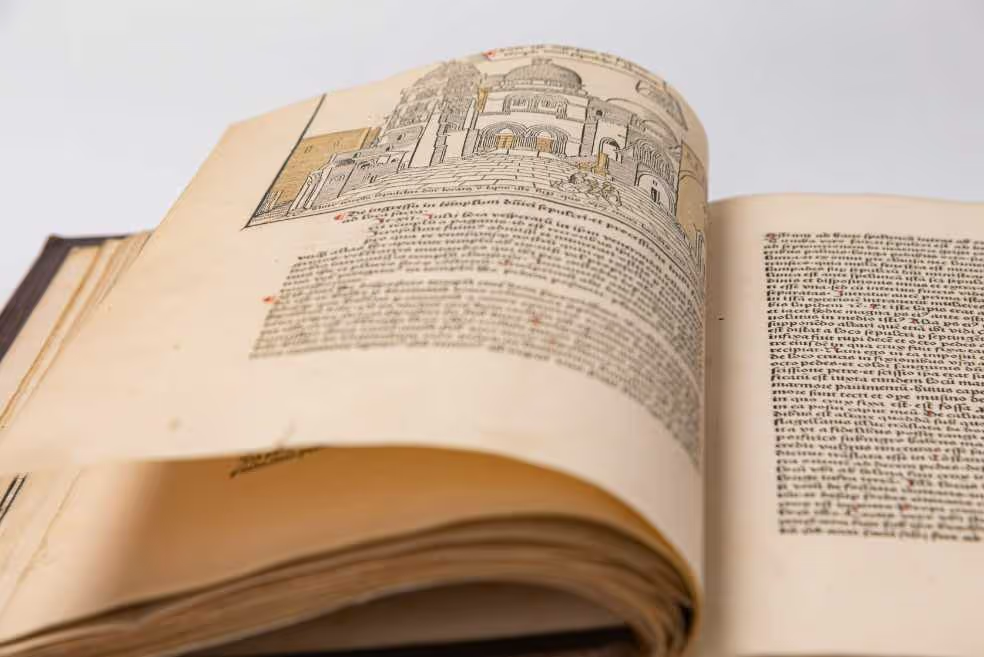

Breydenbach, a German minister and aristocrat, came on pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1483–1484. The expedition was accompanied by an illustrator, who sketched the scenery along the way, and drew the maps and illustrations that came with the book.

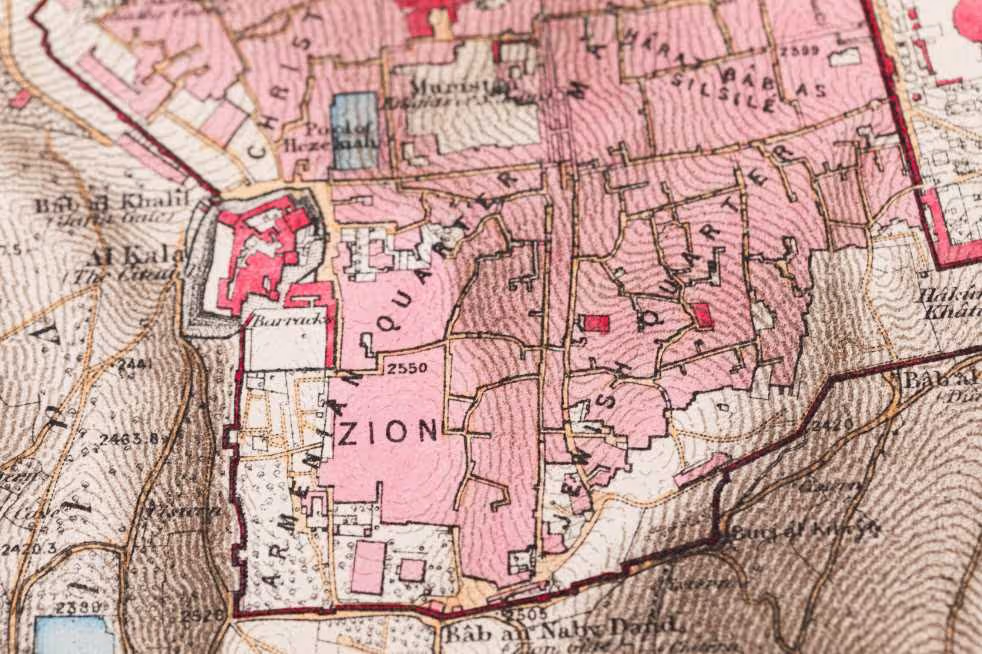

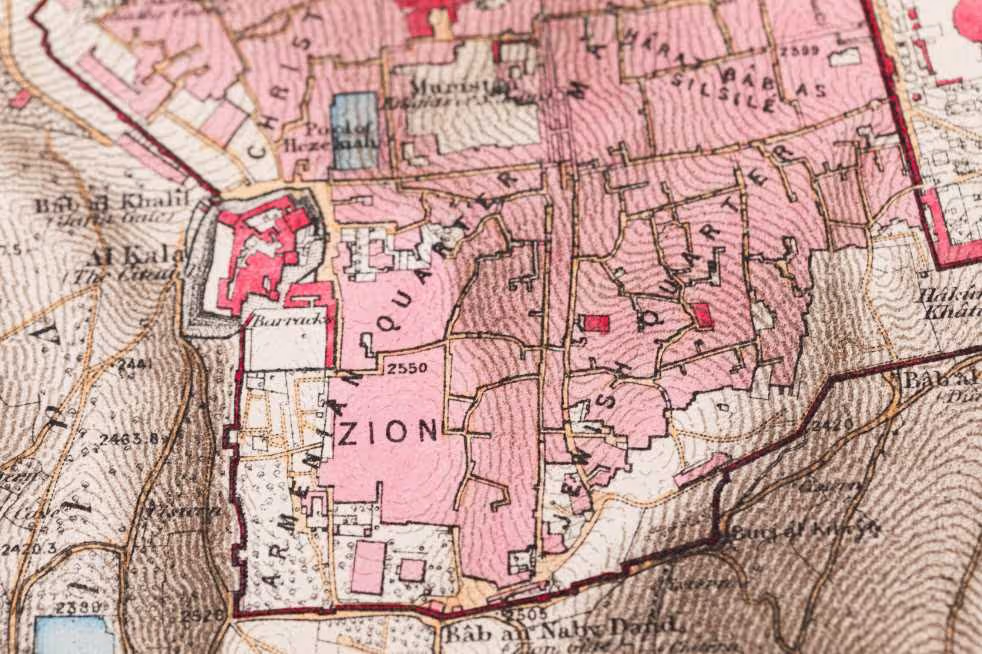

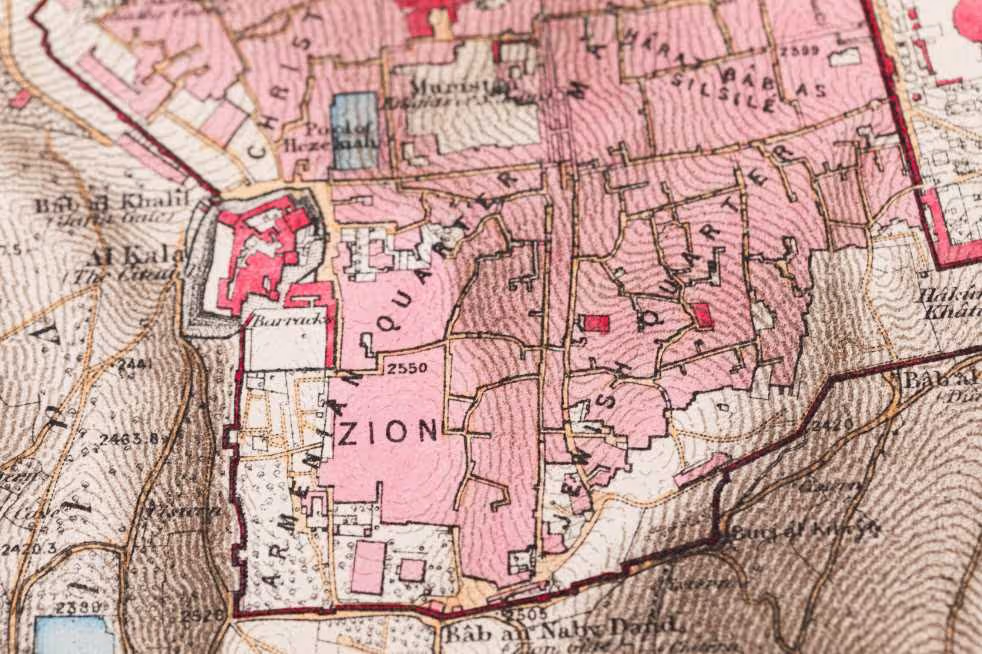

The first modern map of the city was based on the best cartographical knowledge available at that time, and distinguished by its meticulous precision. It was drawn up in the framework of the British Army Ordnance Survey, which produced maps, plans and photographs. The survey team was headed by Charles Wilson (1835–1905), an officer, land surveyor and archaeologist. The team advised the Ottoman authorities on engineering issues, but covertly spearheaded a military intelligence operation that contributed to the conquest of the country from the Turks in the First World War.

Pierotti was an Italian engineer, mathematician and archaeologist, and served as the city engineer of Jerusalem from 1854 to 1861. He was among the first to draw maps of Jerusalem on the basis of precise measurement methods. The text around the map supports the Catholic identification of the Holy Sepulcher as the site of Jesus’ death and burial, versus the site north of Damascus Gate preferred by many Protestants.

Photographs of Jerusalem were part of the British Ordnance Survey that produced the scale map displayed here. The invention of photography a short time before allowed a scientific, “objective” documentation of biblical sites, giving them a quality of “truth.” The unique ability of photography to capture a real image of an object was a moving addition of a “piece of reality” from the Holy Land in the Ordnance Survey file.

The Scottish painter and traveler, David Roberts, was among the first British artists to visit and paint in the Middle East. He traveled the region in 1838–1839, where he made 272 sketches. With some editing and slight “correction” of the landscapes and sites he described, he was able to imbue them with an exalted, eternal “feel,” as well as an impression of documentary truth. Those who paged through his albums felt themselves following in the footsteps of the heroes of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, in the “never-changing” scenery of the Holy Land.

The first step in shaping the rebirth of national “Hebrew music” – as opposed to diasporic “Jewish music” – was collecting and publishing “oriental” Jewish melodies. Idelsohn was the first to record on wax cylinders, and transcribe, the music of the Yemenite, Babylonian, Sephardi and Moroccan Jewish communities. These recordings and transcriptions were the basis of the first volumes of his great work, Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies. The final volumes of the series were dedicated to the European traditions of Ashkenazi Jews.

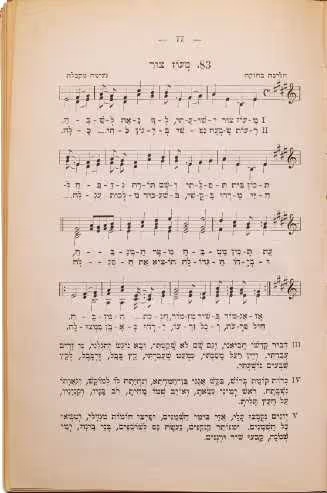

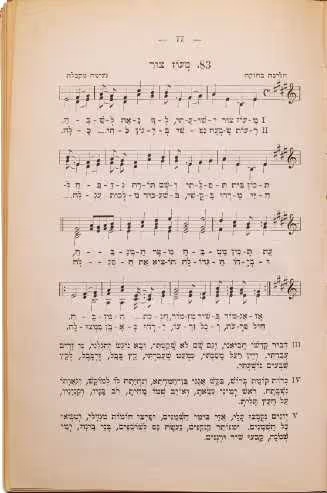

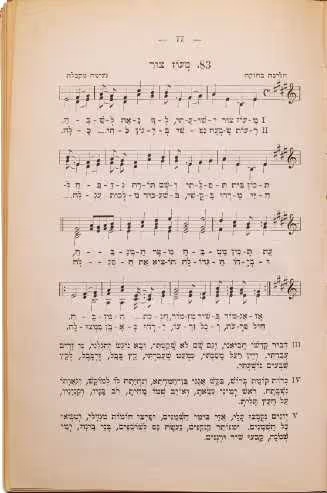

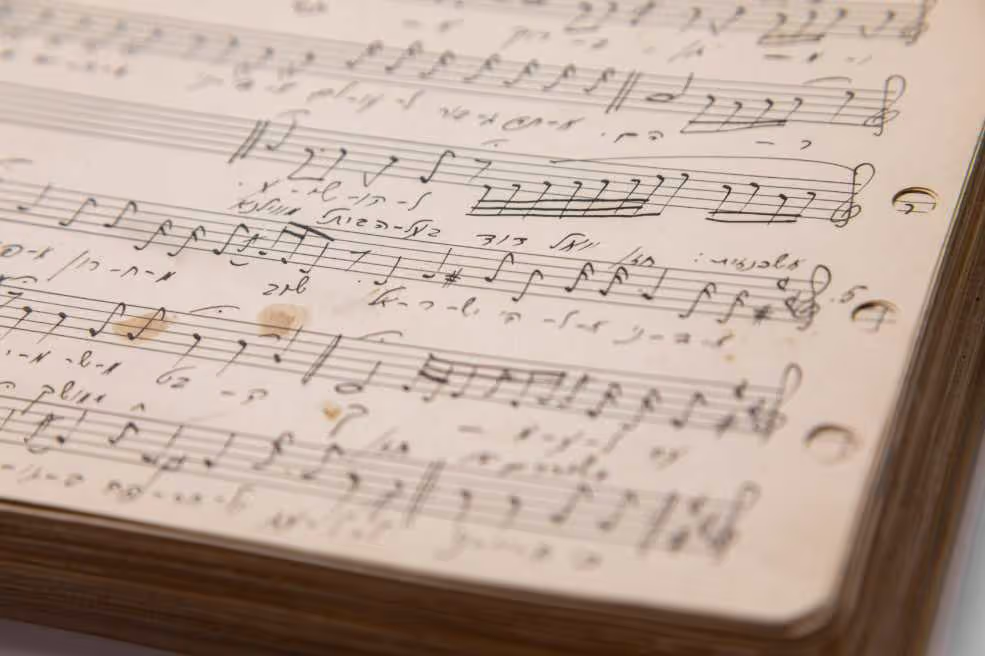

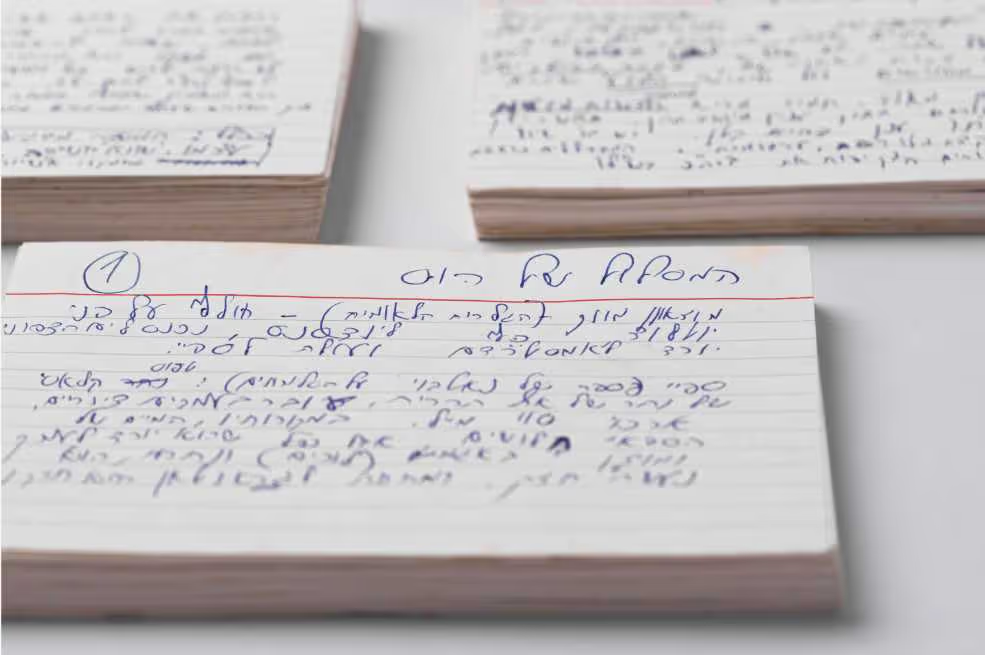

Idelsohn’s most significant song collection, titled Sefer Ha-Shirim (“The Book of Songs”) contains 351 songs in two volumes, intended for Jewish pre-schoolers and school children in Palestine and the Diaspora, some of which he himself composed under his Hebrew name, Ben-Yehuda. The emphasis was on the Hebrew language, and therefore the music notation for the Hebrew songs was written from right to left and the underlying text is in Hebrew letters. The material for the melodies was taken from the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi musical folk traditions since, according to Idelsohn, they have a common root – the root of Israel. One of the last songs in the second volume is “Hava Nagila” in his arrangement for a four-voice choir.

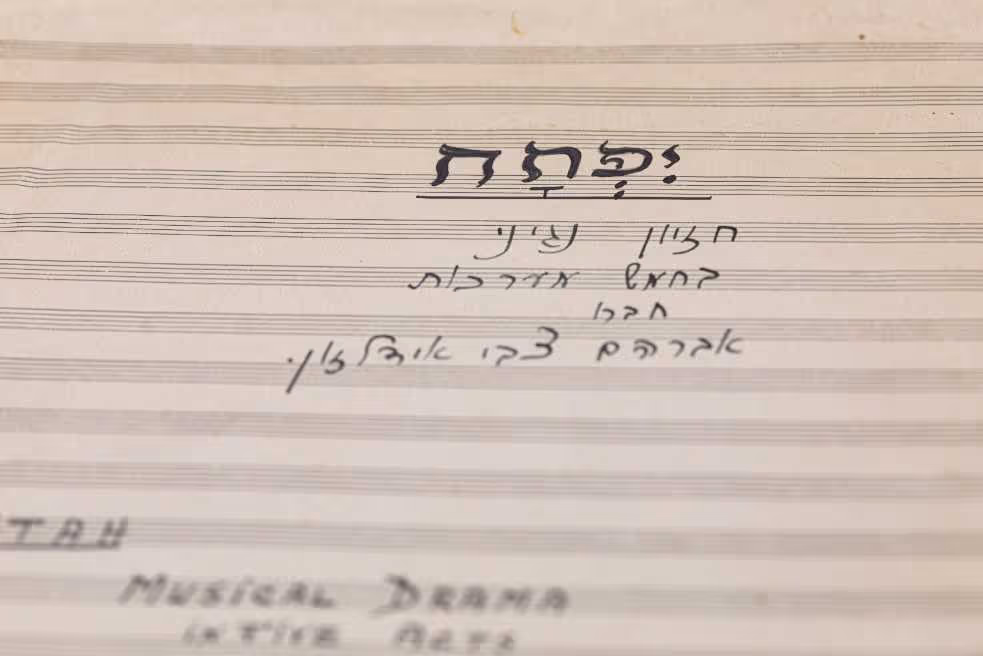

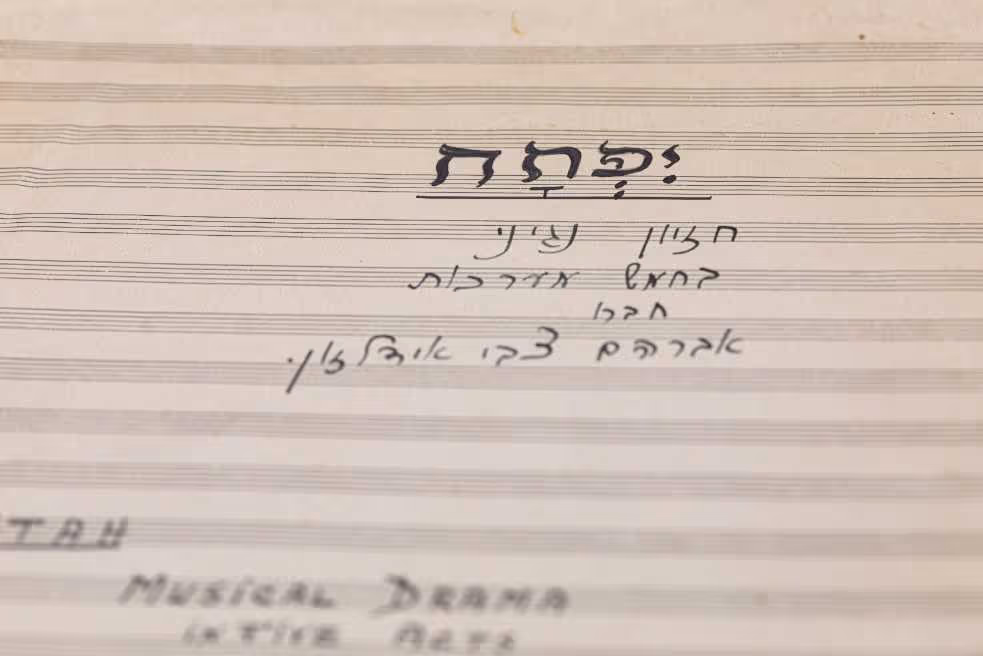

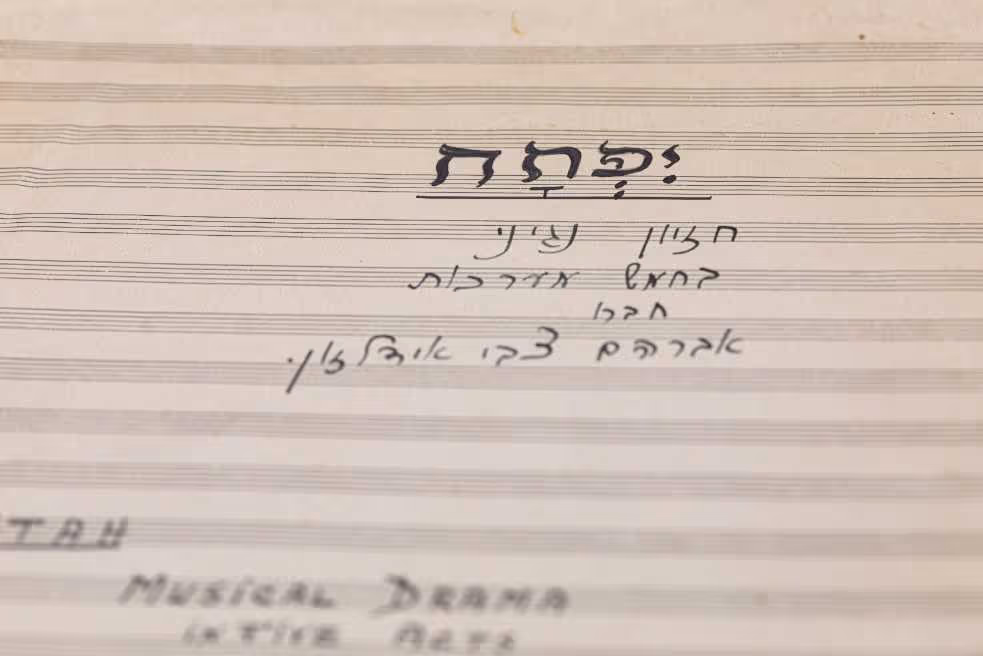

The first opera in Hebrew and the first ever written in the Land of Israel, Yiftaḥ is based on the biblical story of Jephtah, Judge of Israel.

The opera was never performed in its entirety. However, the composition is unique in its musical materials, which are all rooted in the Idelsohn’s earlier ethnomusicological work, in particular the music of the Spanish Jews that he had collected. It seems that through Yiftaḥ, Idelsohn tried to resolve the two conflicting tendencies within him: on the one hand the aspiration towards the peak of Western musical forms, the opera, using harmonic language, and on the other, his own unprecedented immersion in the non-harmonic religious music and folk-music of many old Jewish traditions, and the wish to restore their glory.

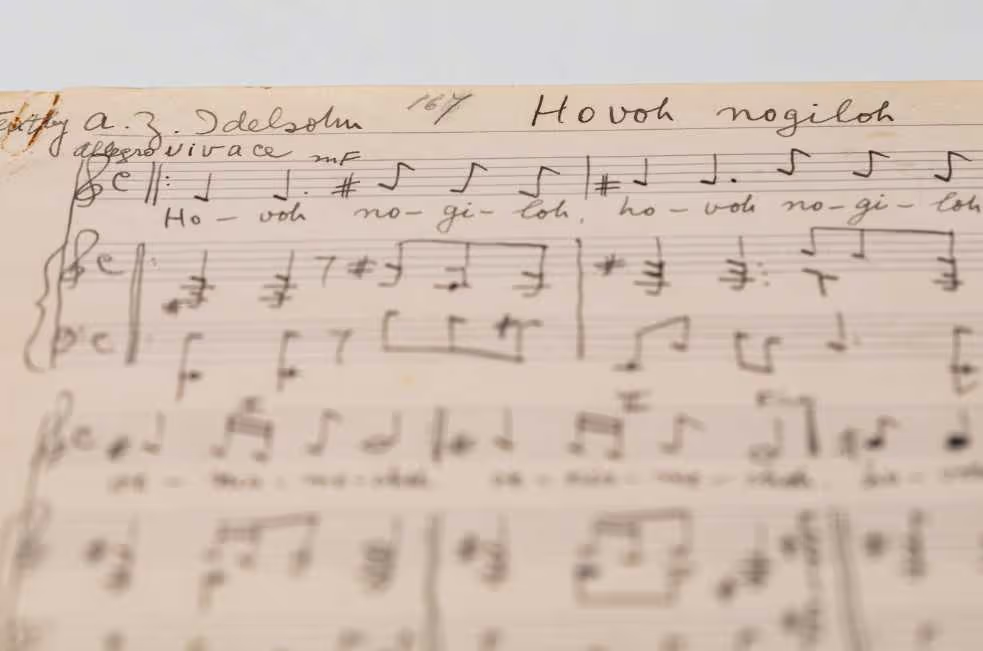

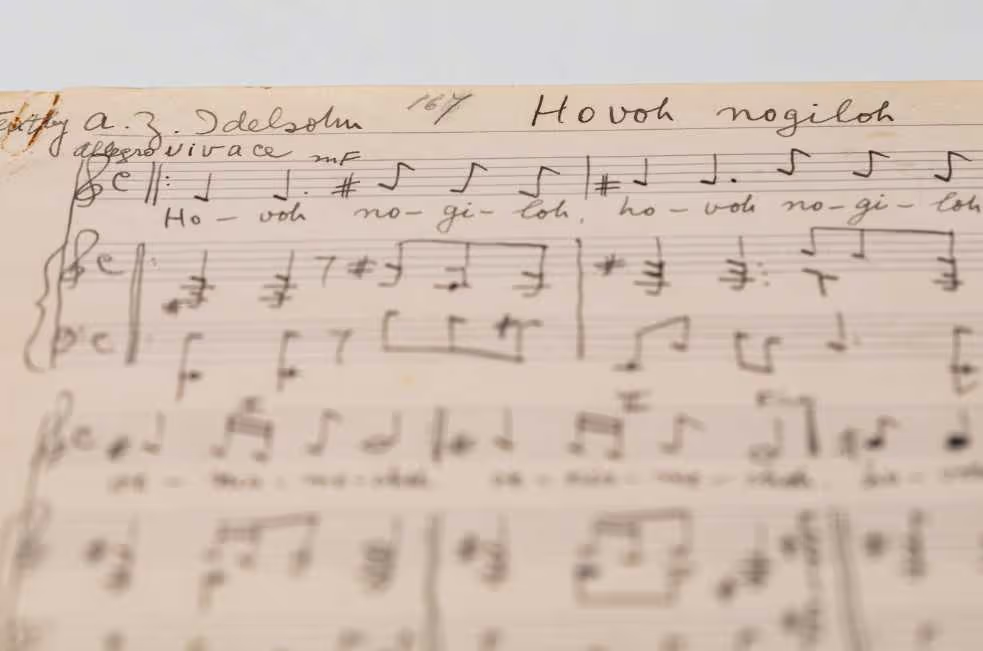

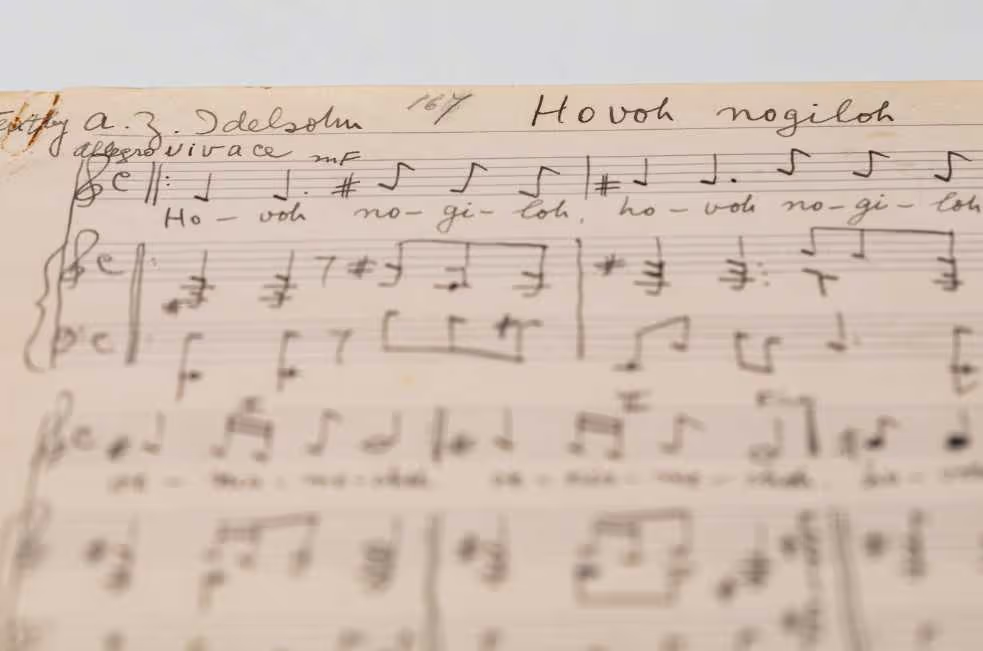

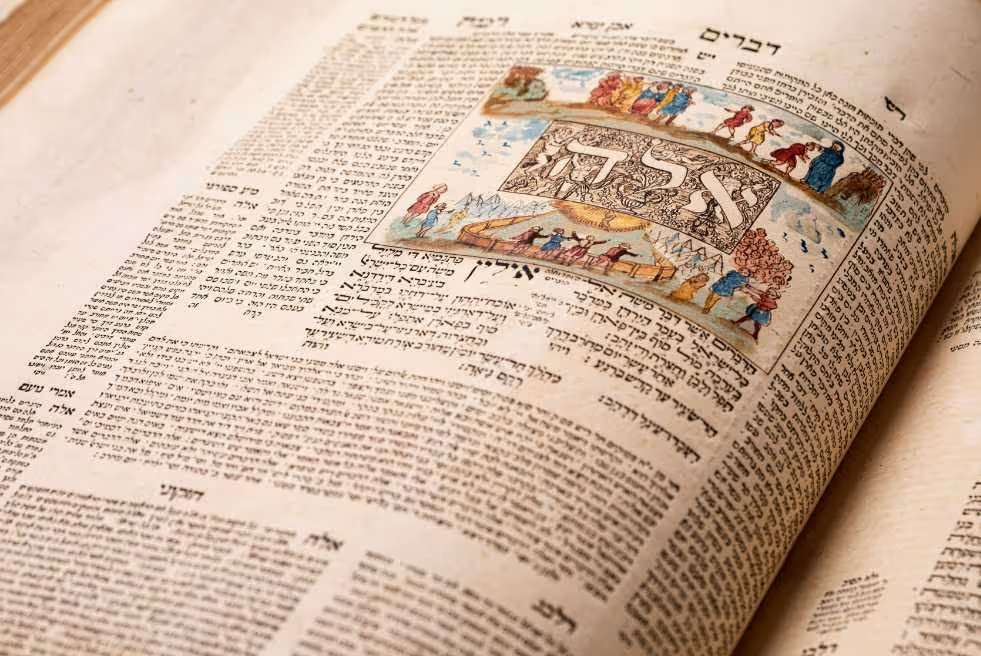

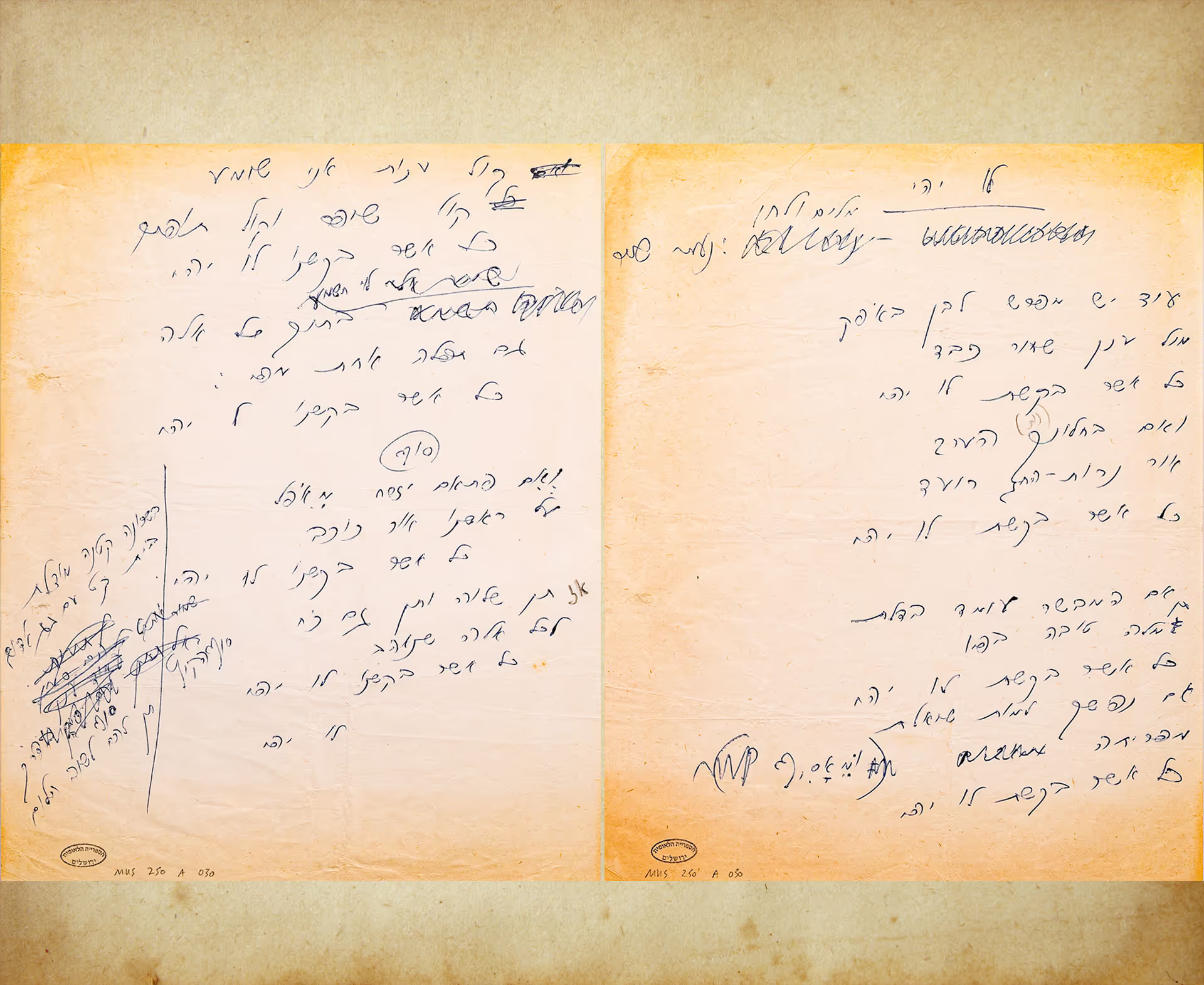

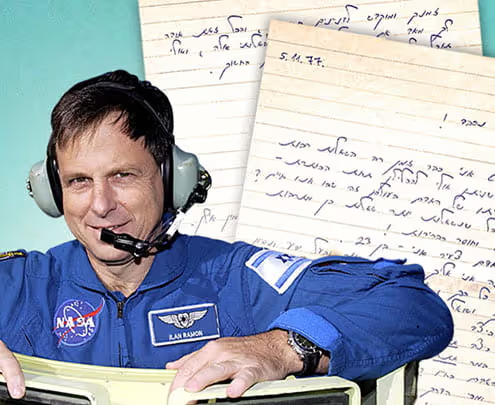

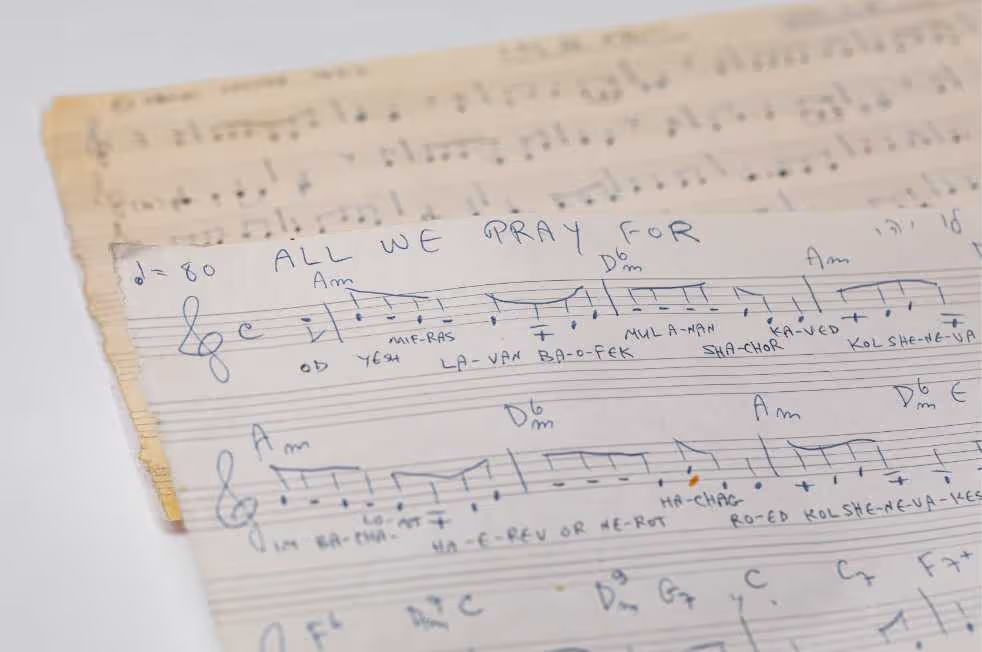

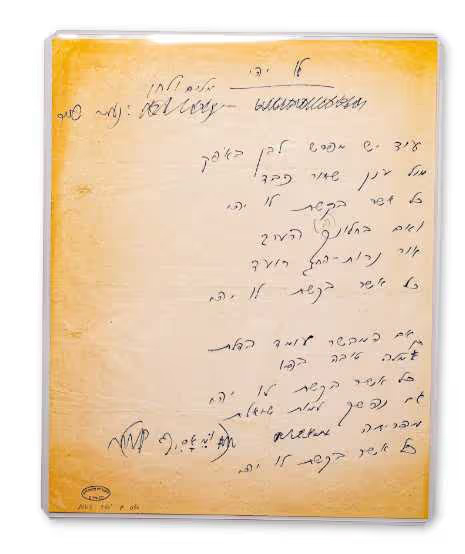

“Hava Nagila” (“Let us rejoice”) was compiled by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn in 1917 for the occasion of the Balfour Declaration and the welcoming ceremony for General Allenby in Jerusalem. The song expressed the enthusiasm of the Zionists returning to their homeland. He adapted a festive Hasidic melody, changed the order of the musical motives and added the text “hava nagila ve nismeḥa, hava neranena, ‘uru aḥim belev sameaḥ.” In his manuscript, presented here, the arrangement is for voice and piano.

Idelsohn recorded the song with a small men’s choir on a commercial record in Berlin in 1922. Soon after, it was recorded by several popular singers, choirs and instrumental ensembles. Today it is one of the most popular Hebrew songs in the world.

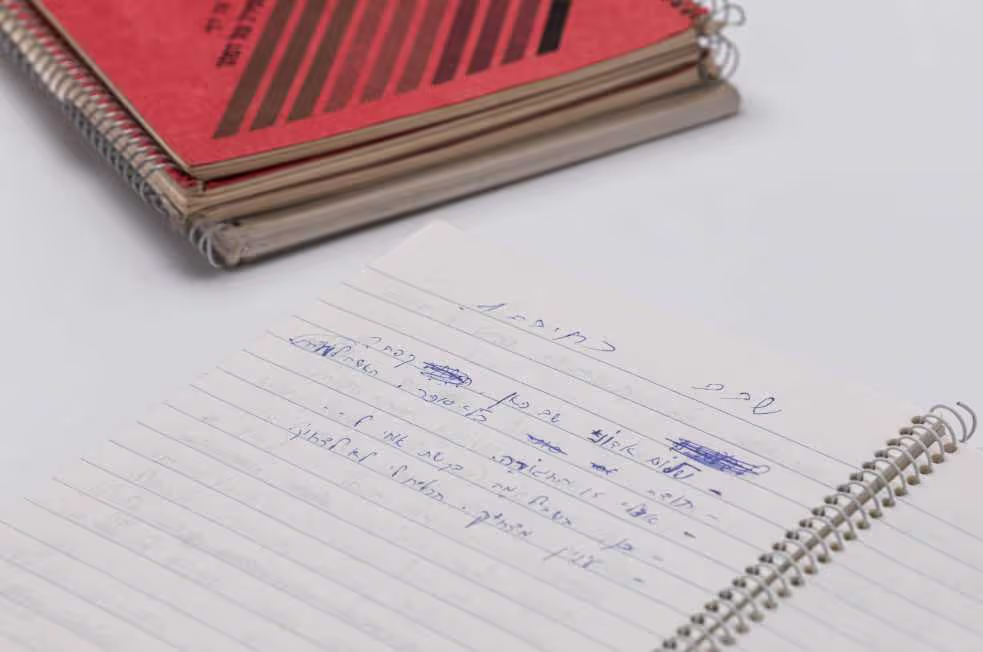

Idelsohn intended to present the practices various Jewish traditions had in common in order to find “the original Jewish song.” The first volume of the book, summarizing what Idelsohn gathered from compiling Oriental musical traditions, was written as a pedagogical book for those who wish to study Jewish music. The main part of the book is devoted to extensive theoretical presentation of the biblical cantillation system, in historical context, through an abundance of musical examples. The second volume of the book, which was not published, is dedicated to the song of the synagogue. All the musical examples are transcribed from right to left.

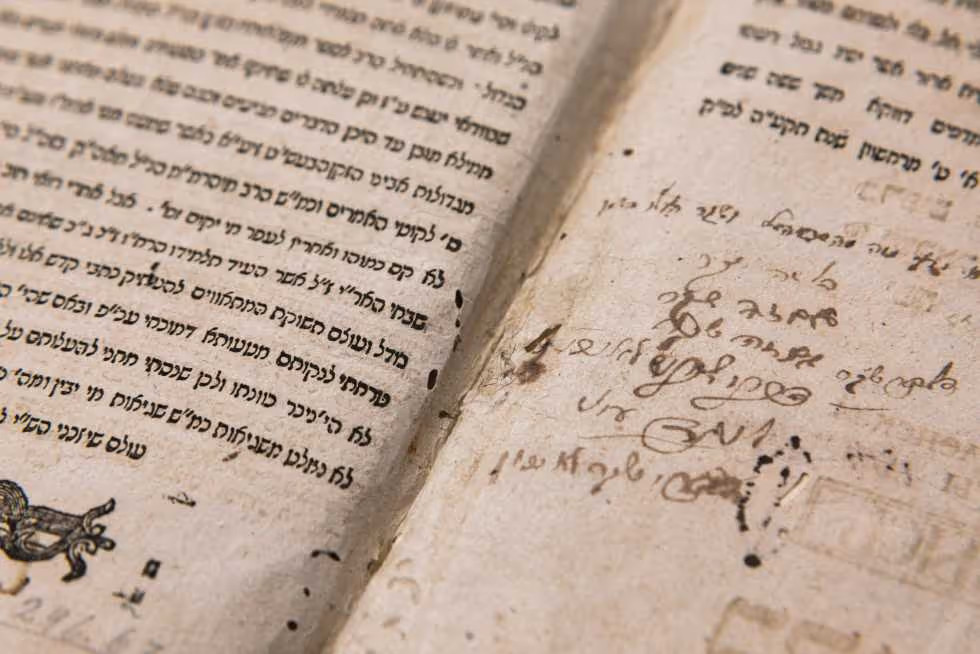

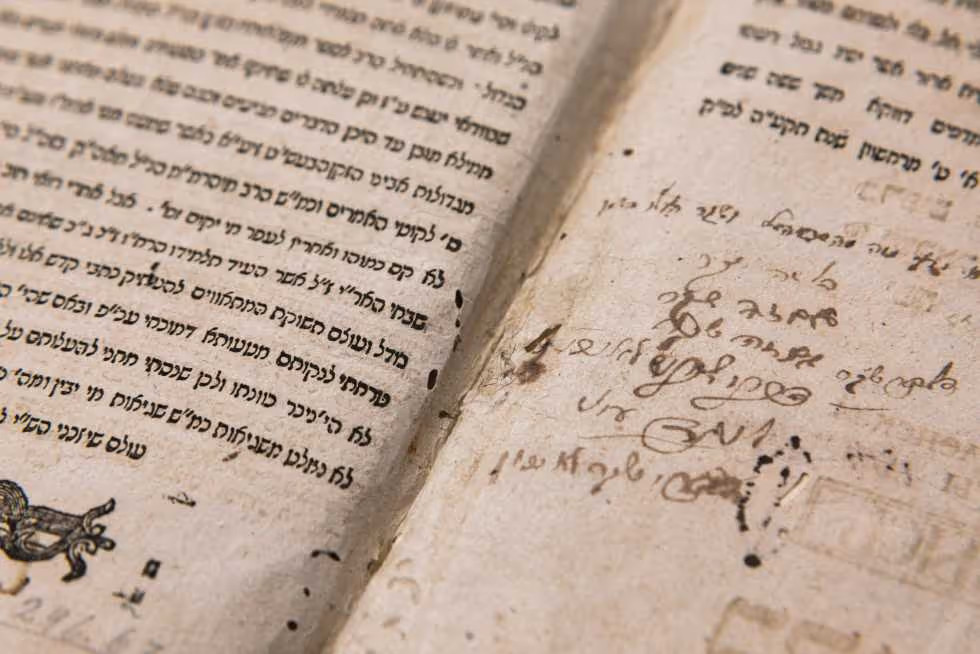

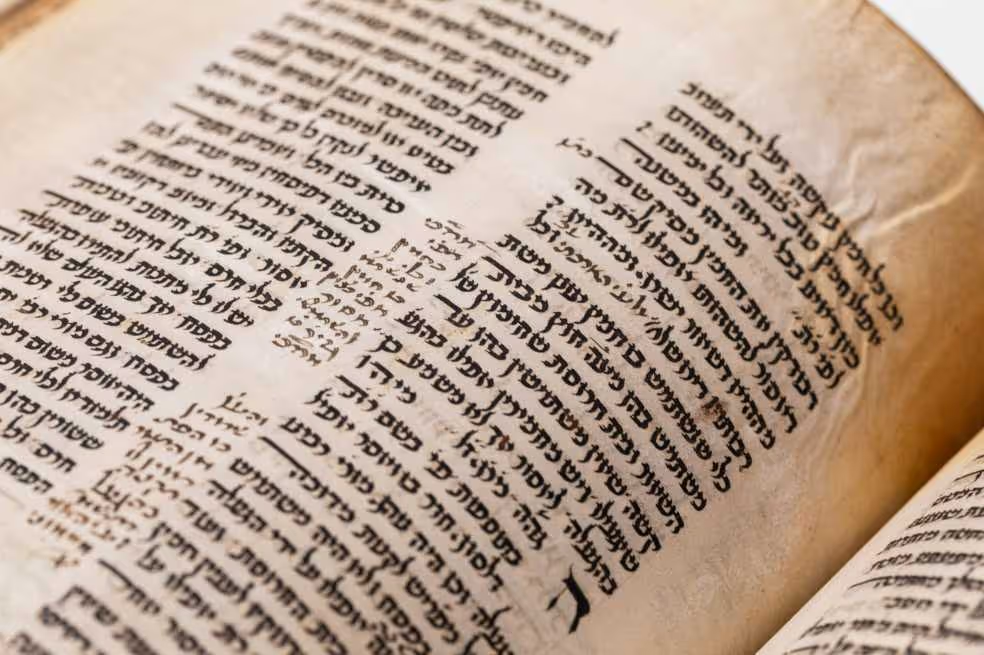

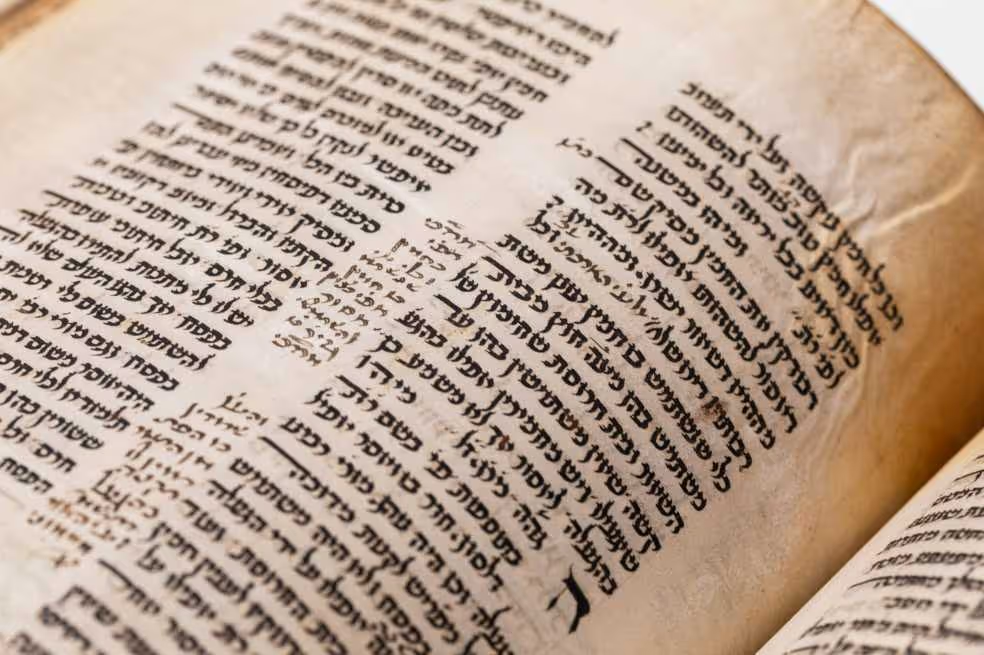

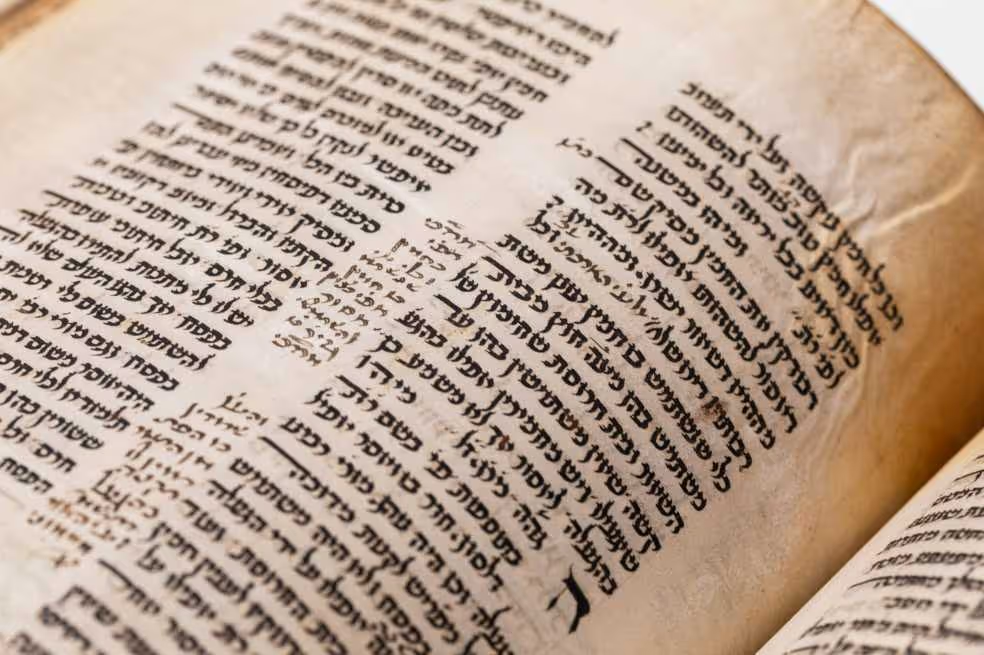

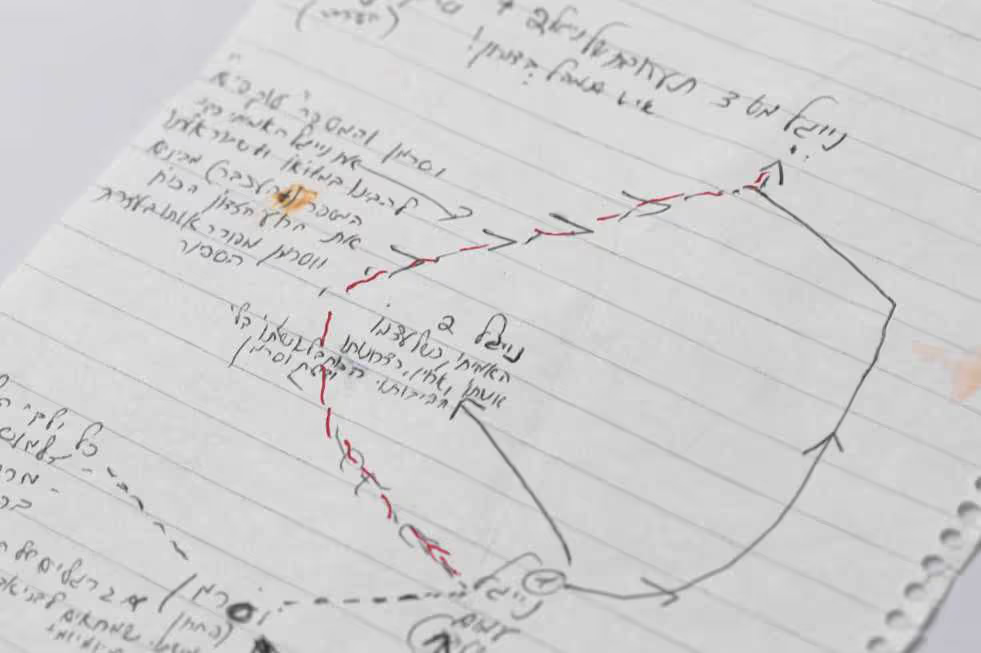

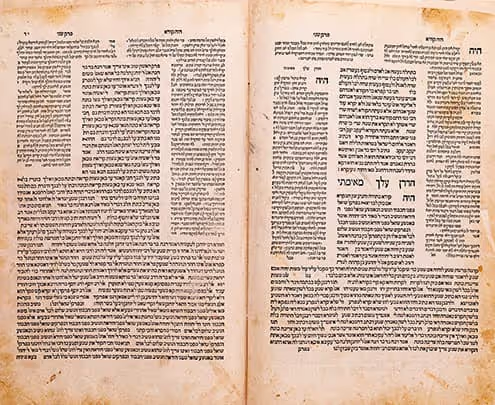

Previous printings of the Talmud consisted of isolated sections of the text appearing separately. The first complete printed edition, shown here, enabled its distribution and influenced its reception as a fundamental text in Jewish culture. The design of the Talmud page in this edition swept the world of Jewish learning and has been faithfully reproduced in every subsequent edition of the Talmud. Daniel Bomberg, the publisher, was a Christian printer born in Antwerp whose assistants, including both Jews and Jewish converts to Christianity, helped him locate manuscripts, proofread and typeset the text.

A translation of the Bible into Syriac Aramaic. The translation was apparently made in the 2nd century for use by the Jewish community in north-eastern Syria (Upper Mesopotamia). As Christianity became more dominant in the region from the 3rd century onwards, the translation was adopted by the Syrian Christian communities who still use it today.

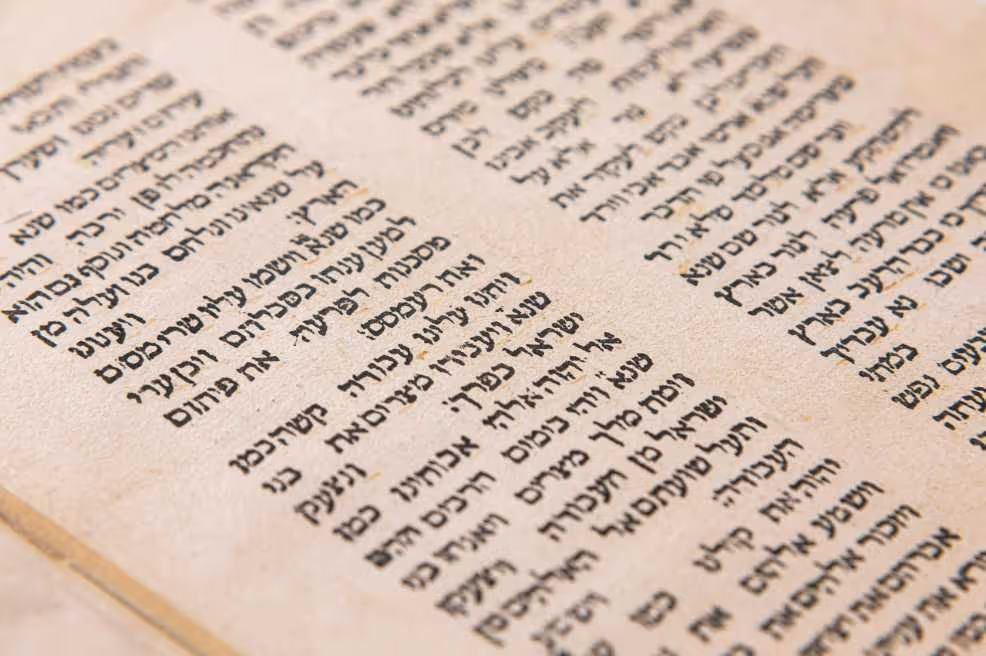

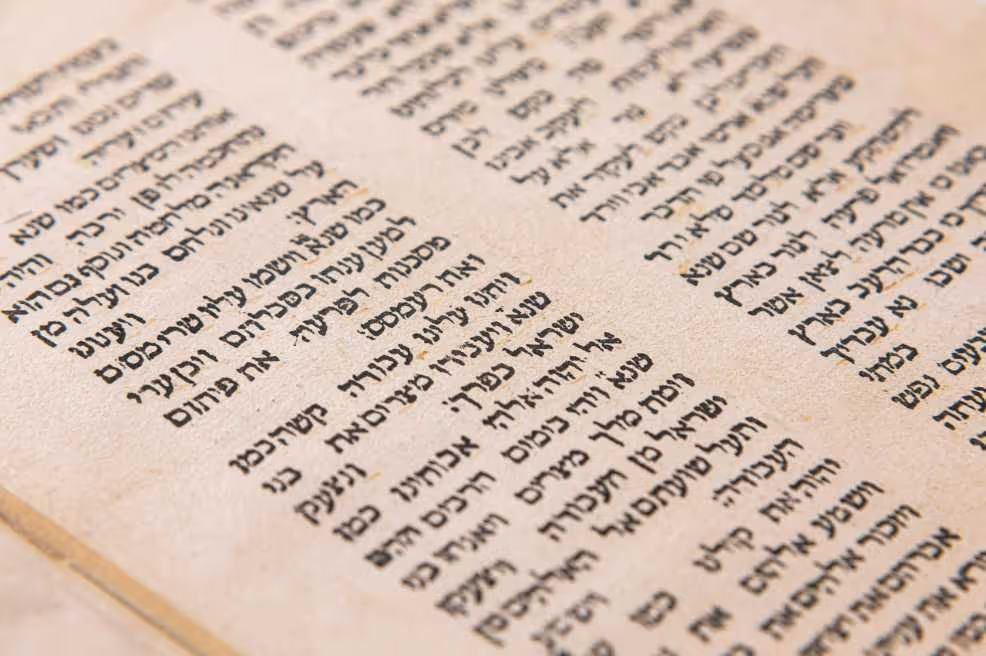

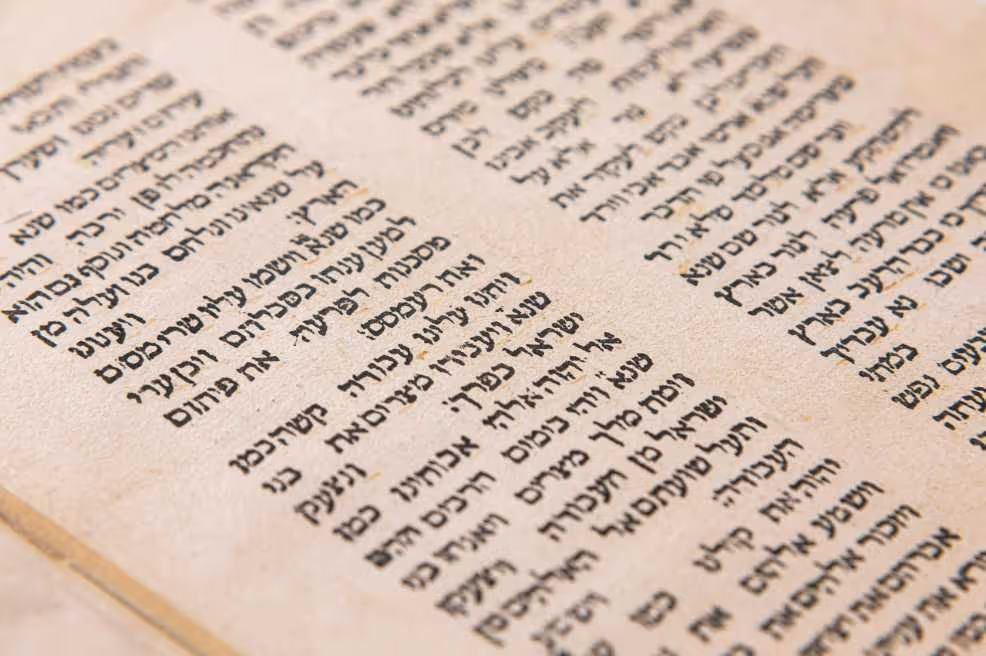

This is the first Hebrew Bible to be printed. The edition, numbering 300 copies, was unusually large for its time. The first pages are the first vocalized Hebrew text ever printed. The rest of the text is not vocalized, apparently due to production issues. Rabbi David ben Yosef Kimḥi (RaDaK) (1160–1235) was one of the greatest biblical commentators and one of the most important Hebrew grammarians.

This is the first vocalized Hebrew Bible to be printed. The small format reduced its price and made it easier to distribute and carry during travel and emigration.

The Soncino family was active in Italy and the Ottoman Empire, and were among the pioneers of Hebrew printing. The family press was active for decades and had a reputation for meticulousness. Its accurate productions were highly influential on the development of Hebrew printing.

A collection of stories in Hebrew about the life and works of the 18th century founder of the Hasidic movement, the “Baal Shem Tov.” The text, written and edited in the 1790s, is the first published collection of Hasidic stories on the themes of the sanctity and greatness of the Hasidic Master.

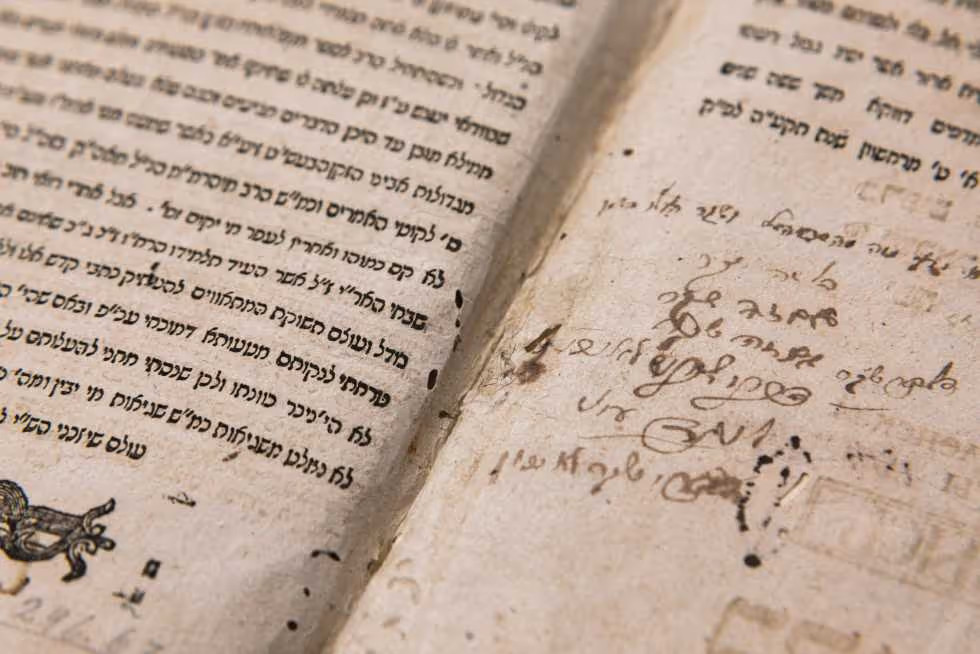

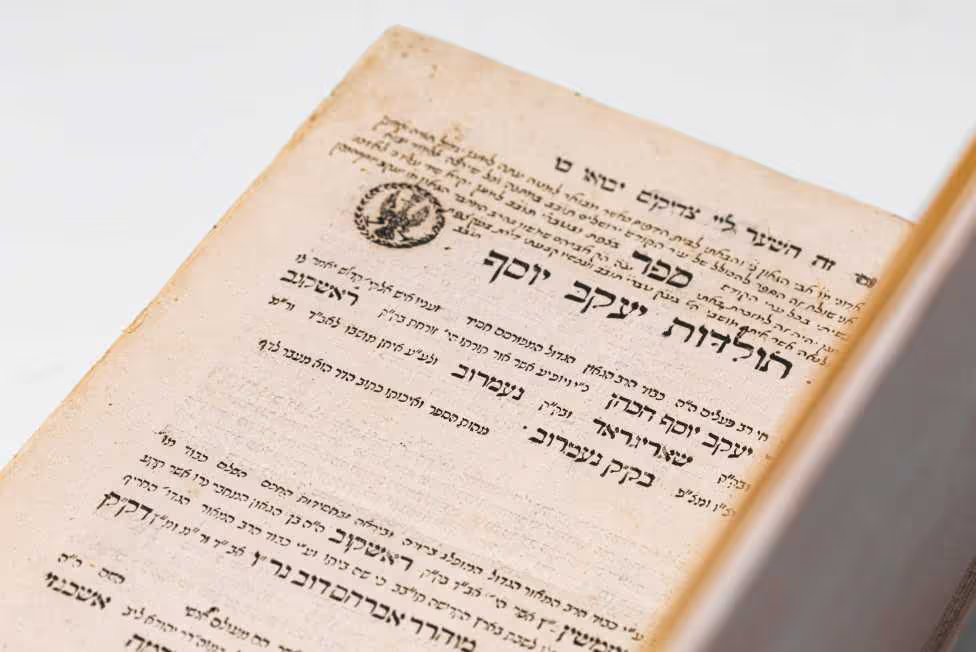

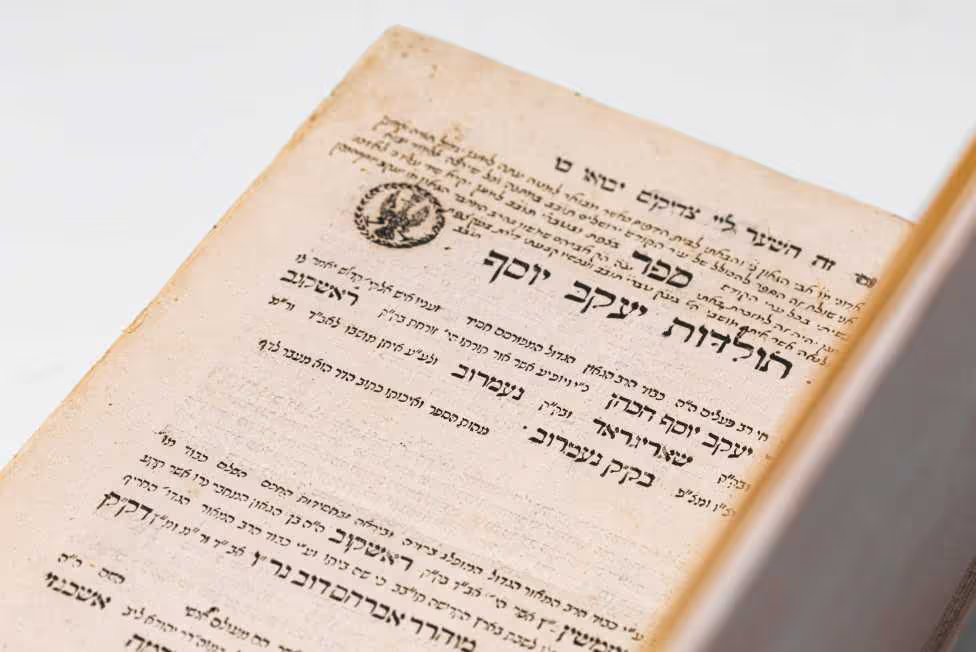

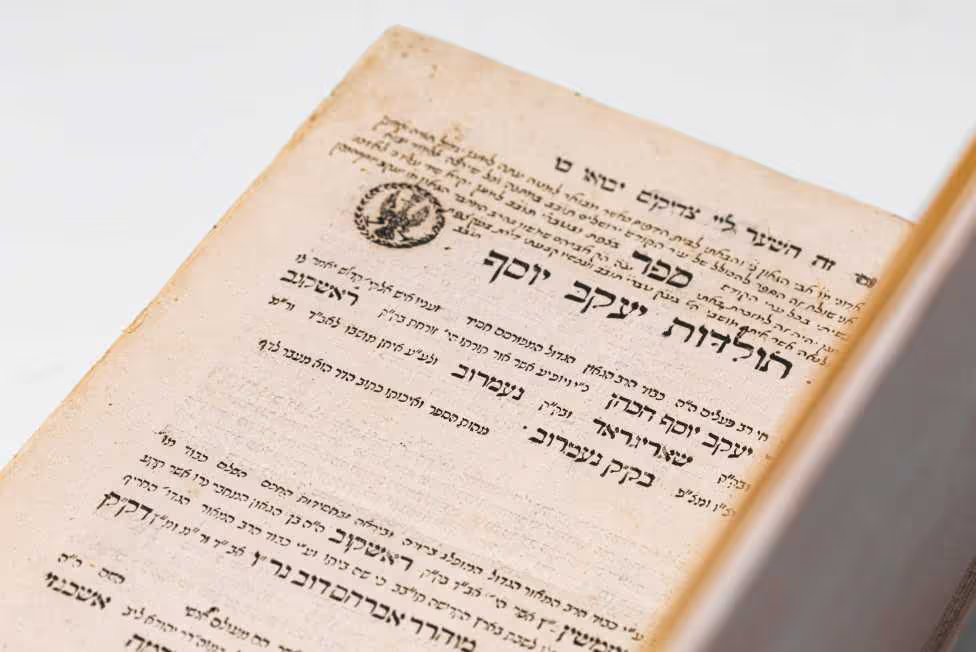

This book by Rabbi Yaakov Yosef of Polonne, an early and important disciple of the Baal Shem Tov is the first Hasidic work to be published. It is important not only for its primacy but also because it contains many sayings and teachings that the author heard directly from the Baal Shem Tov. The work is arranged in the form of a commentary on the weekly Torah reading. The copy exhibited here is from the first edition.

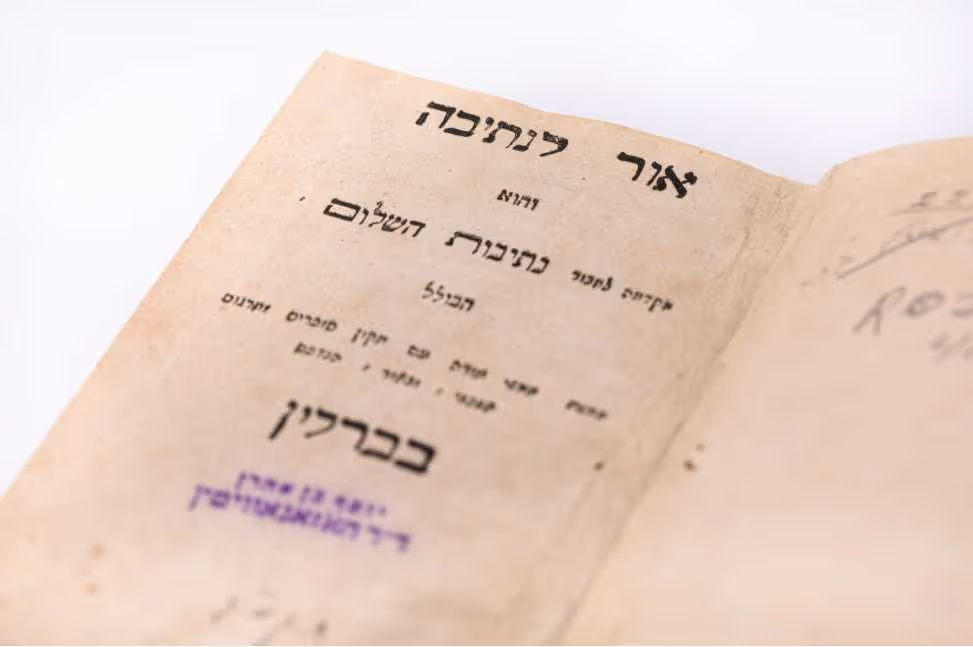

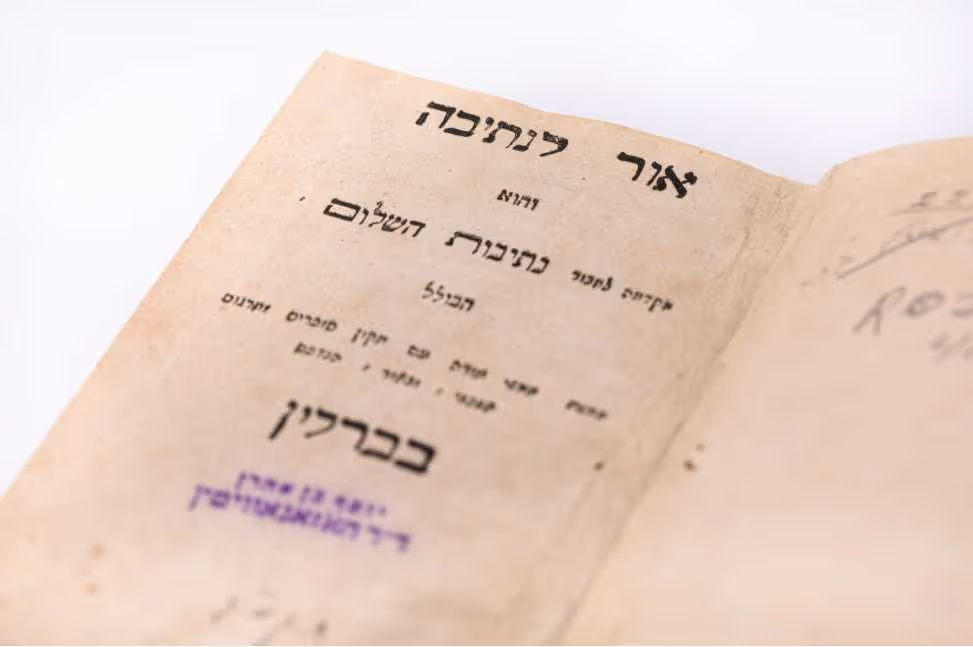

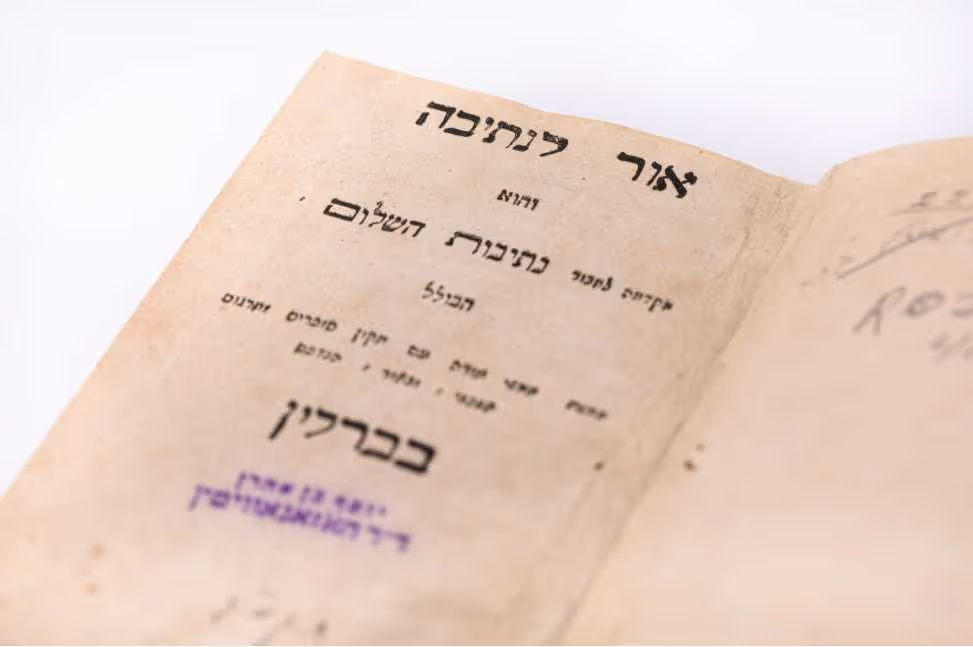

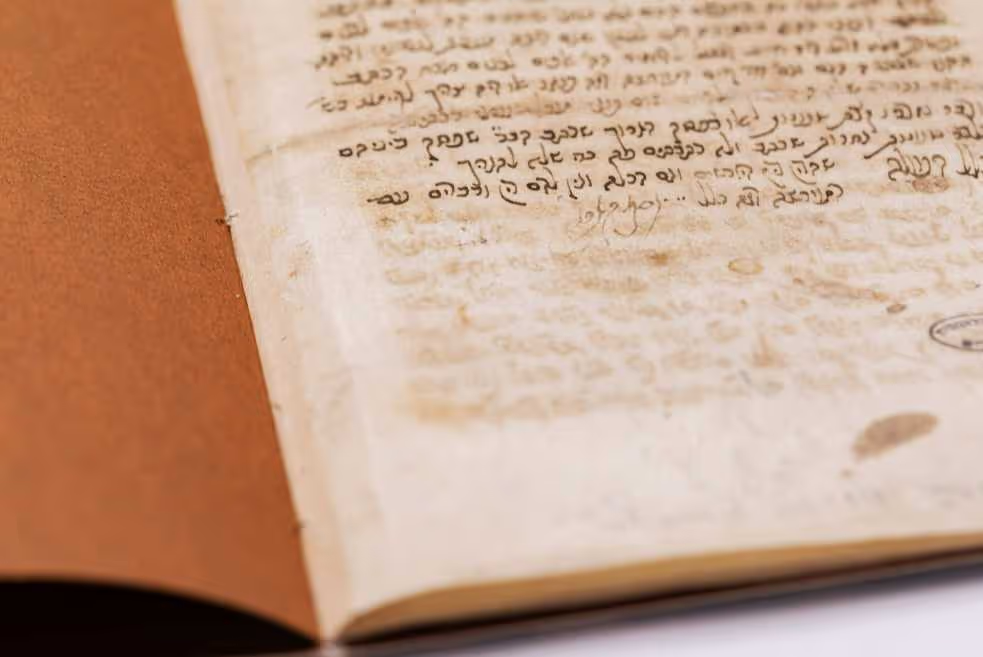

The work shown here is an introduction to a translation of the Torah in German written in Hebrew script. The translator, German Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, was one of the founders of the Jewish Enlightenment movement, and the translation is one of the movement’s foundational texts. Its target audience was German-speaking Jews who could not read German script, and it reflects Enlightenment ideas and concepts. In spite of the moderate content of the commentary, it aroused fierce opposition from contemporary rabbis.

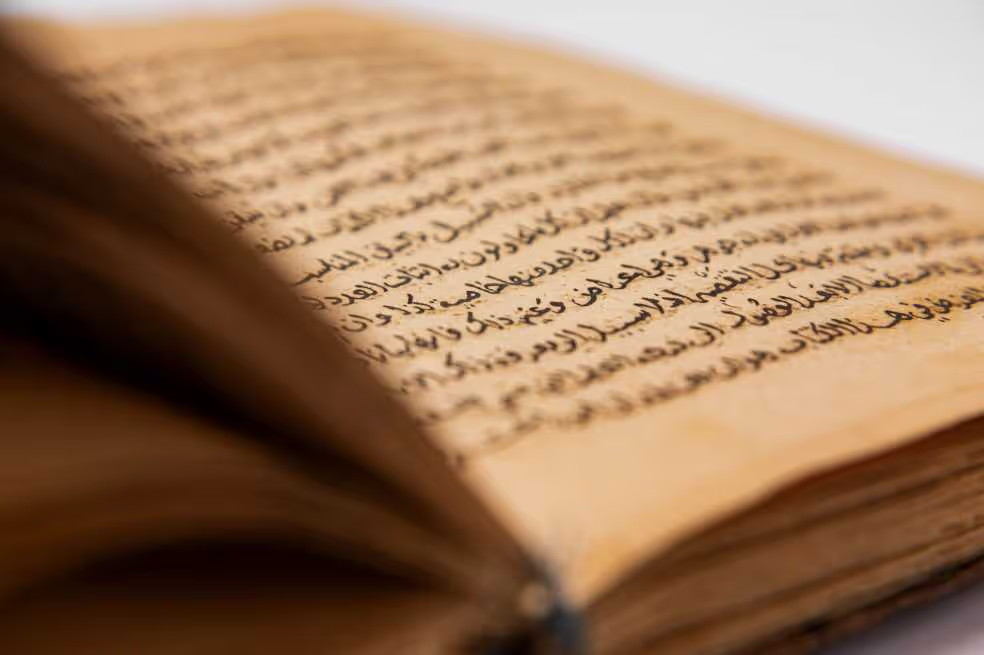

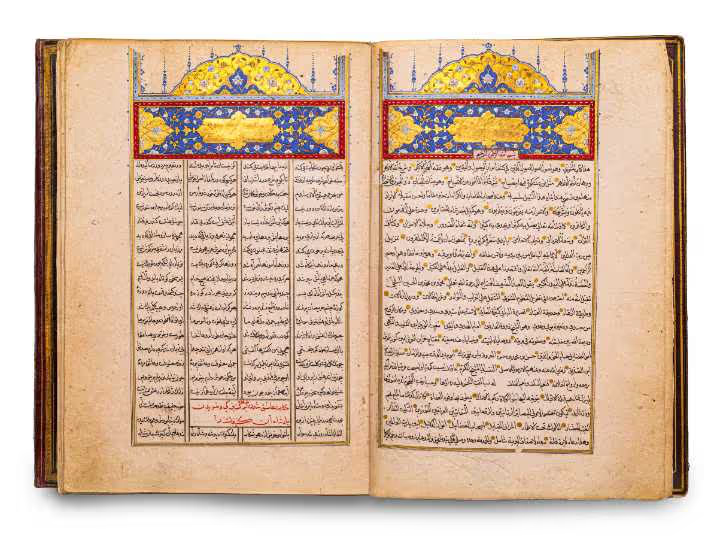

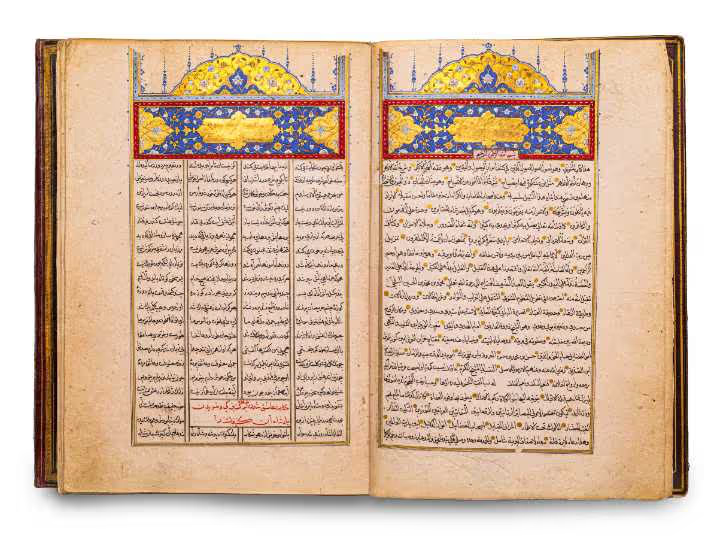

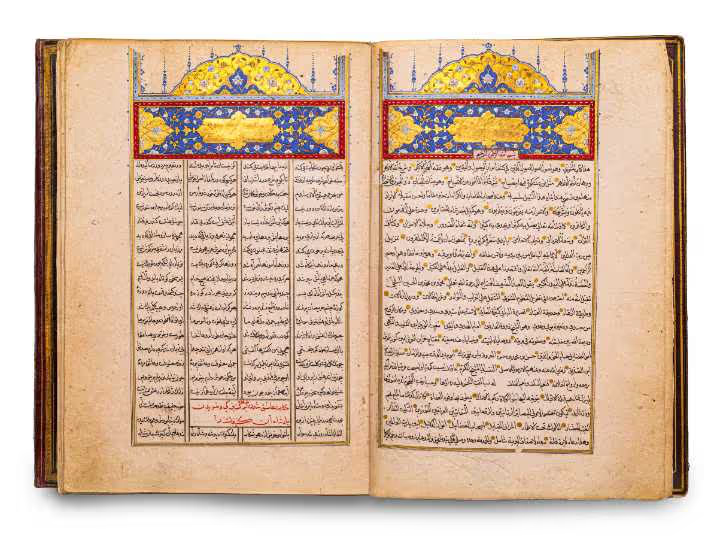

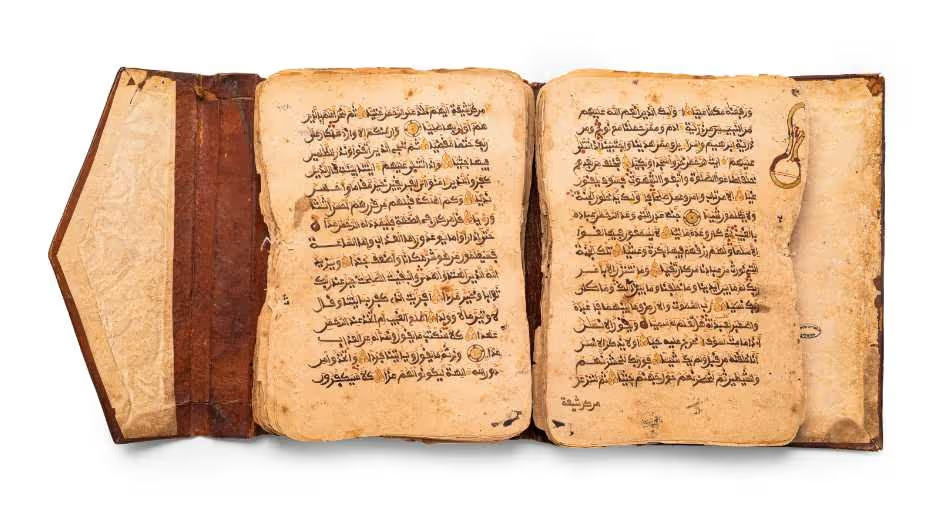

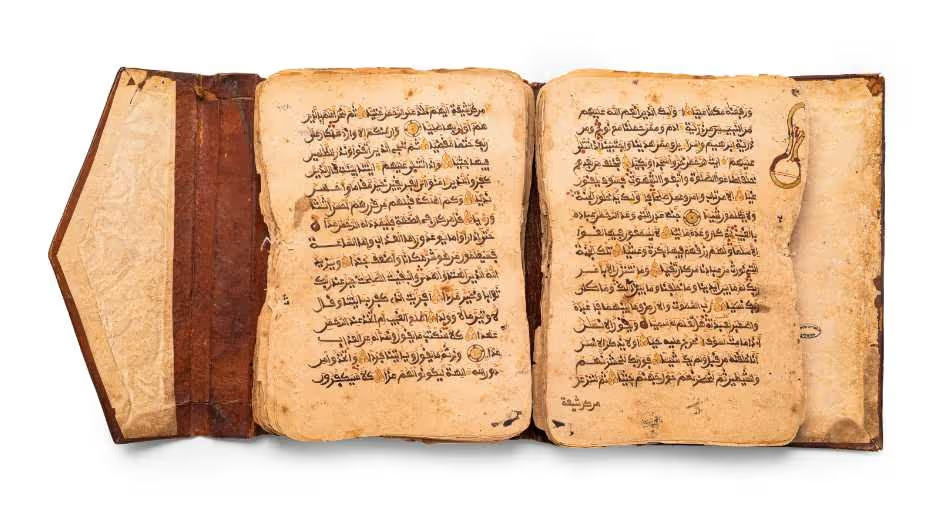

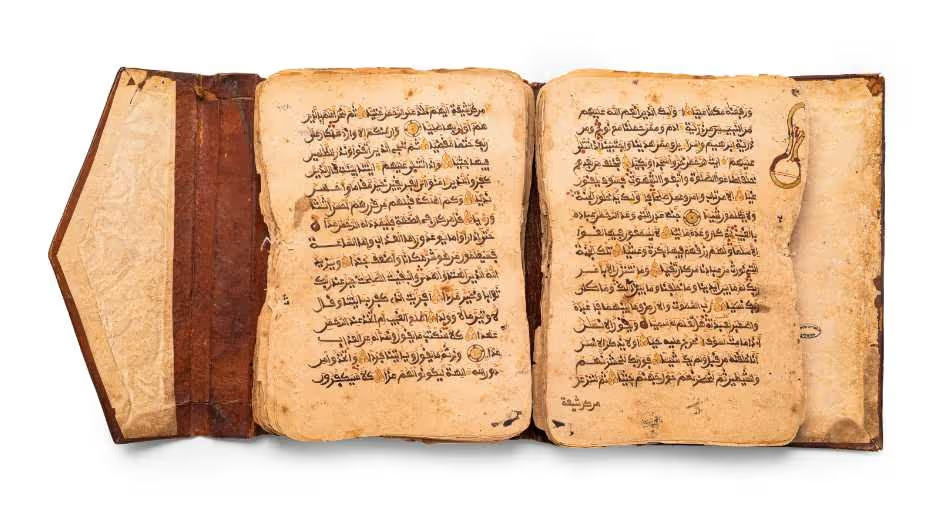

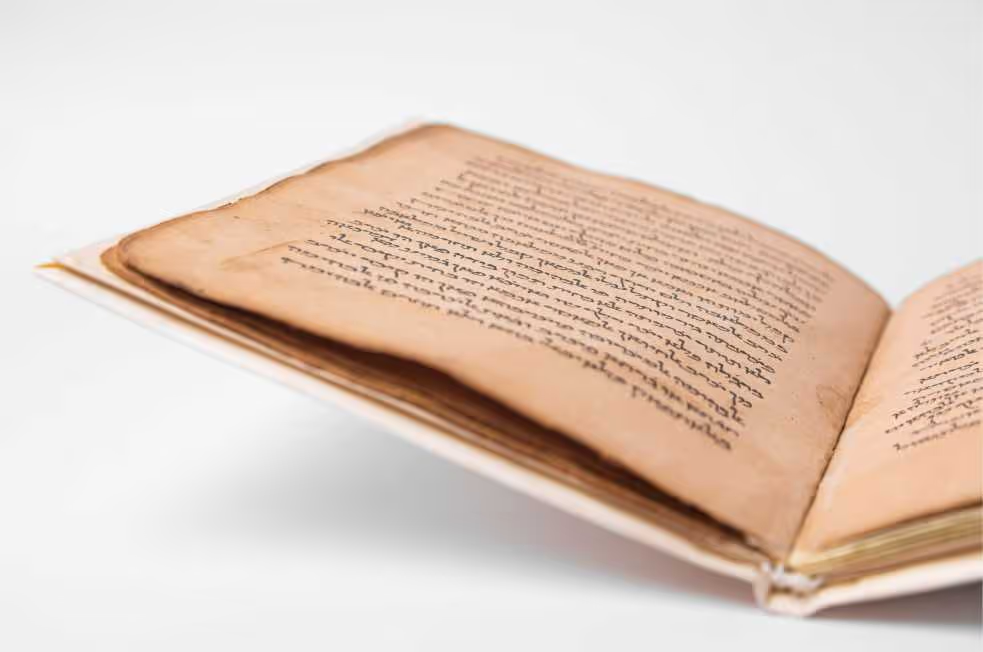

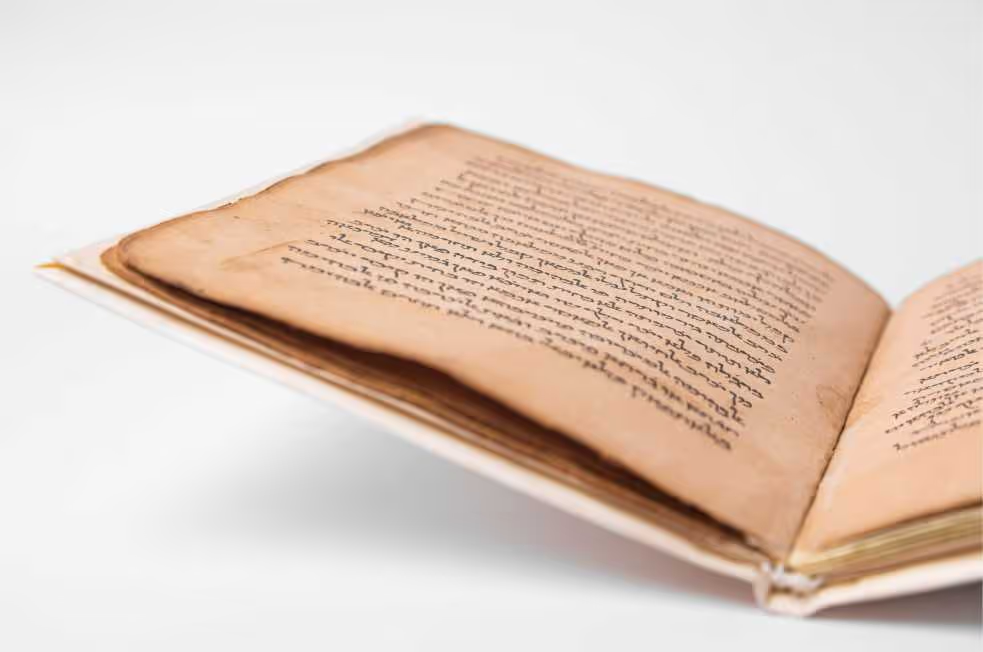

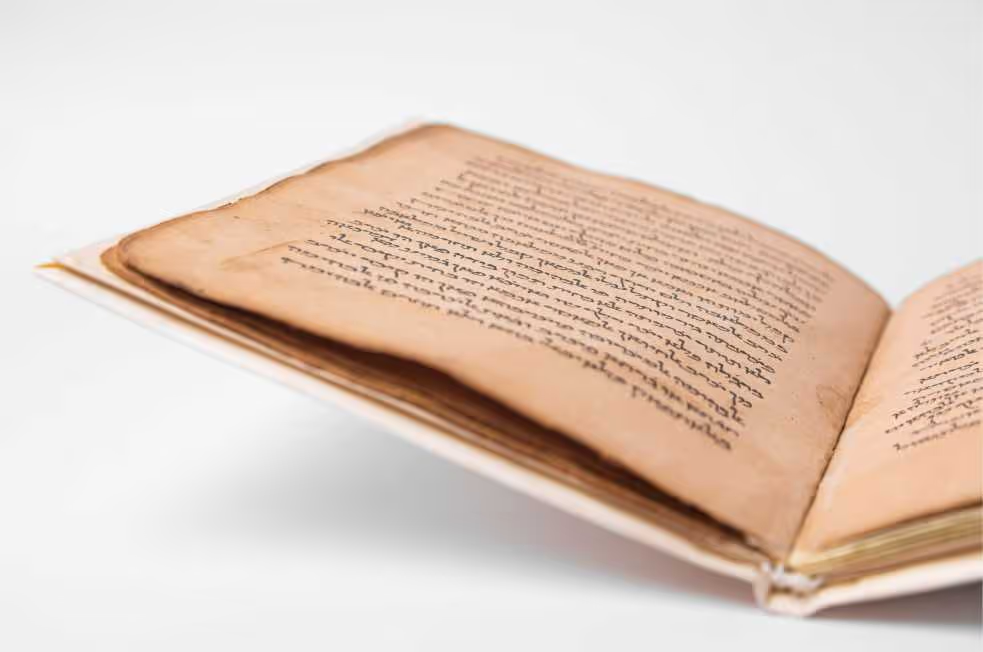

Hadith, meaning literally “report,” is the name for the traditional accounts of the Prophet Muhammad’s words and deeds. Hadith is second in authority only to the Quran as a source for jurisprudence, ritual, and other areas of life. The hadith were collected in the 9th century and sorted into great compilations by subject. According to his biographers, Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj traveled throughout the Islamic world collecting hundreds of thousands of reports attributed to the Prophet. The resulting collection was called “Ṣaḥīḥ” or “authentic,” and it is considered one of the two canonical collections of hadith in Sunni Islam.

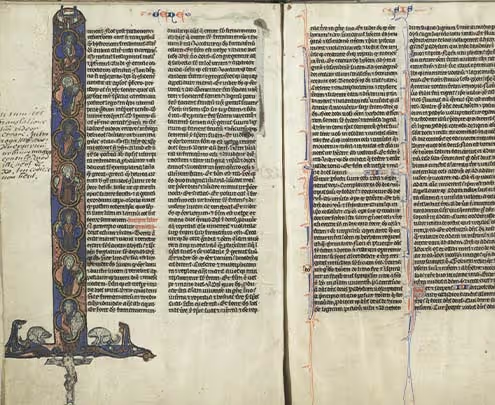

An ornate copy of the Vulgate, the official Latin translation of the Christian Holy Scriptures authorized by the Roman Catholic Church. The Vulgate includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (“Old Testament”), the books of the Apocrypha not included in the Hebrew canon, and the books of the Christian Bible (“New Testament”).

An ornate copy of the Vulgate, the official Latin translation of the Christian Holy Scriptures authorized by the Roman Catholic Church. The Vulgate includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (“Old Testament”), the books of the Apocrypha not included in the Hebrew canon, and the books of the Christian Bible (“New Testament”).

An ornate copy of the Vulgate, the official Latin translation of the Christian Holy Scriptures authorized by the Roman Catholic Church. The Vulgate includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (“Old Testament”), the books of the Apocrypha not included in the Hebrew canon, and the books of the Christian Bible (“New Testament”).

An ornate copy of the Vulgate, the official Latin translation of the Christian Holy Scriptures authorized by the Roman Catholic Church. The Vulgate includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (“Old Testament”), the books of the Apocrypha not included in the Hebrew canon, and the books of the Christian Bible (“New Testament”).

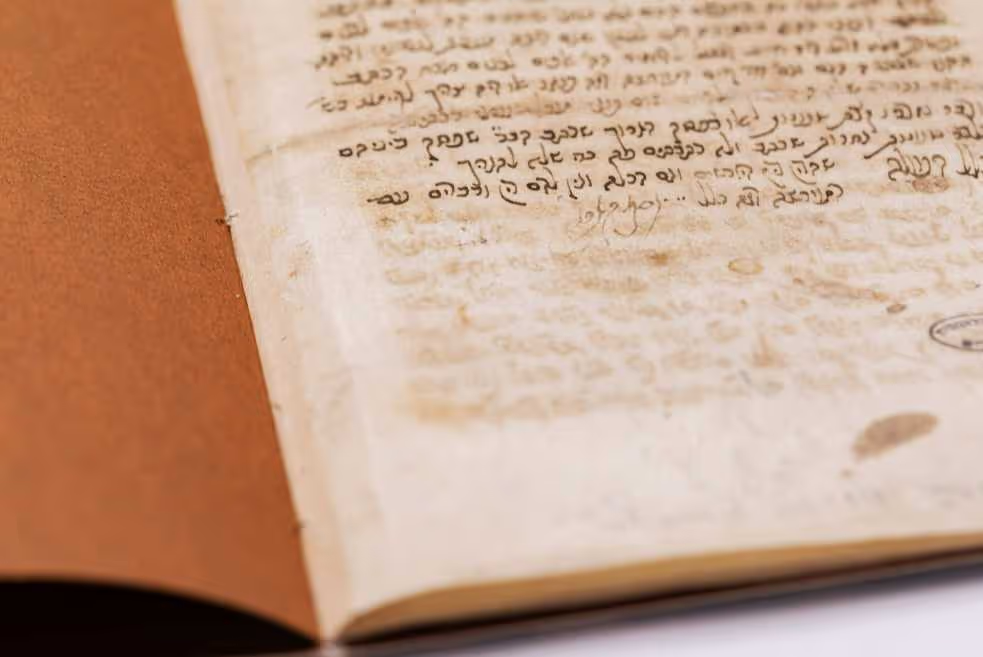

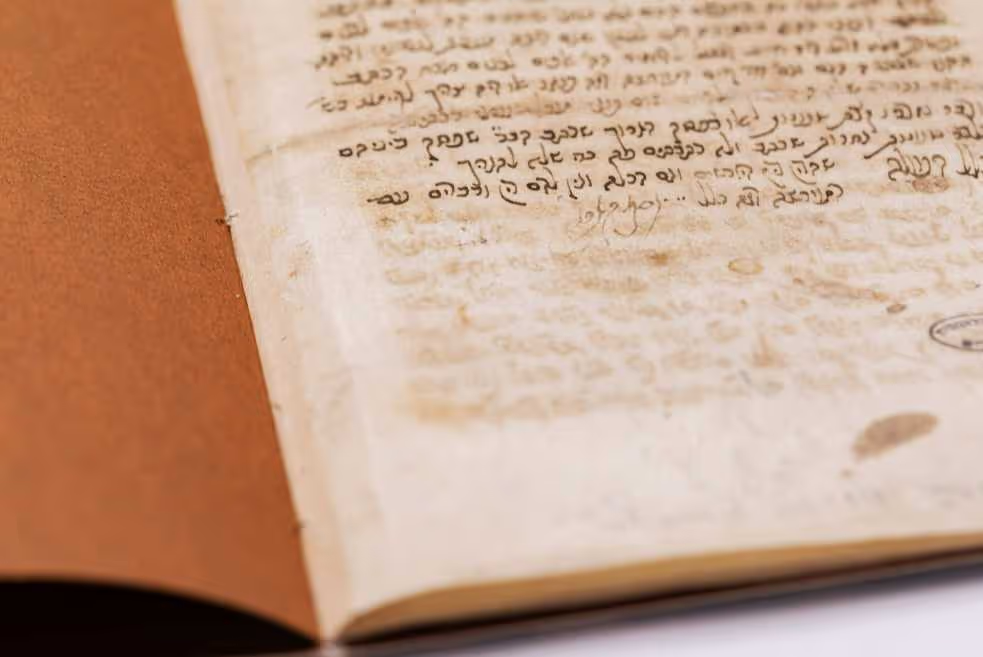

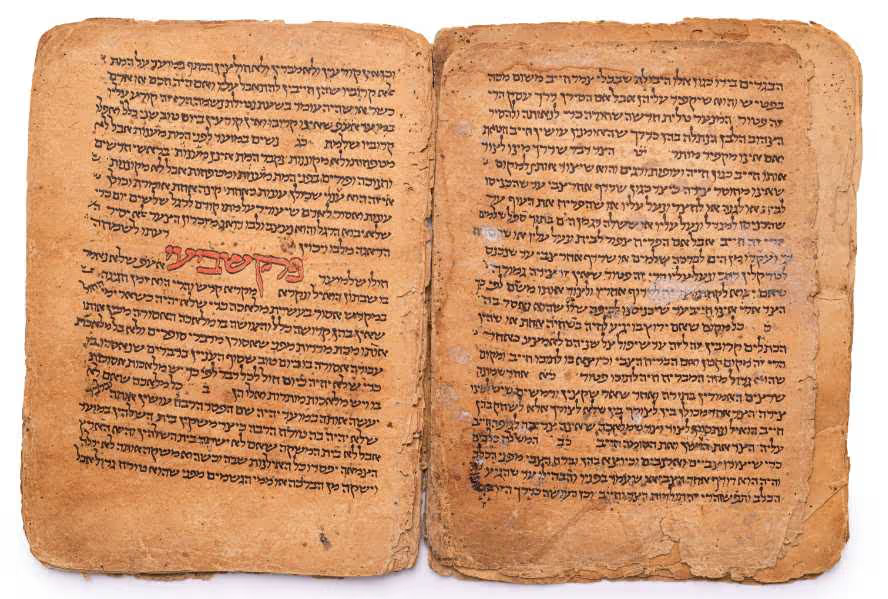

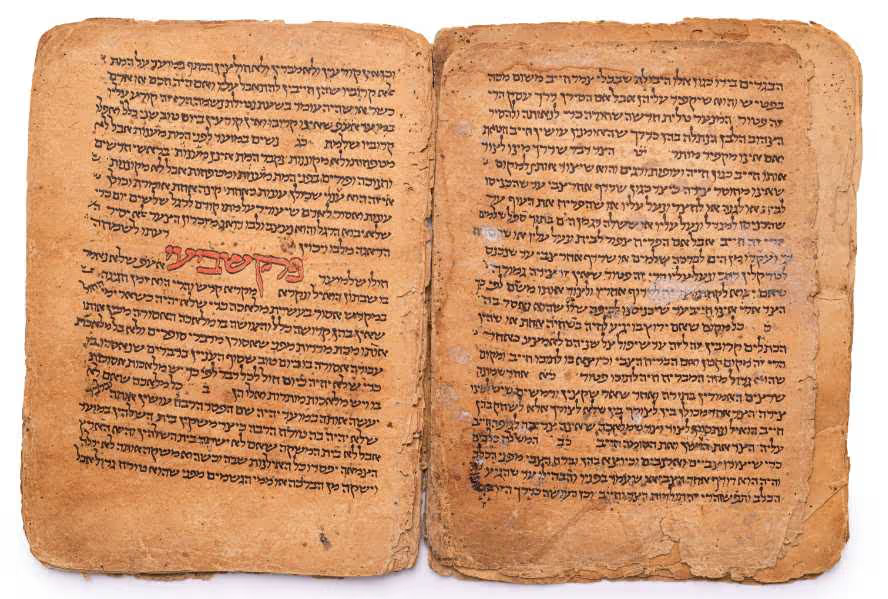

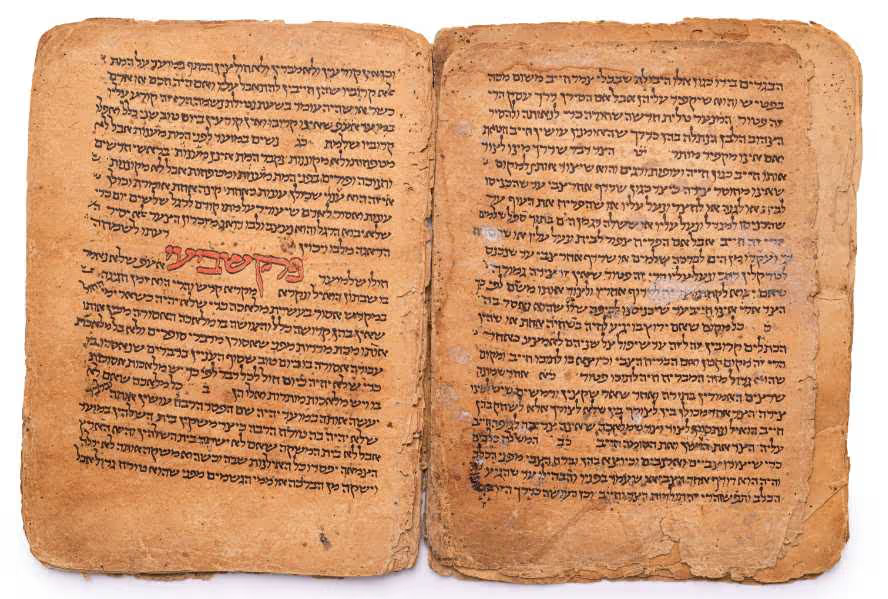

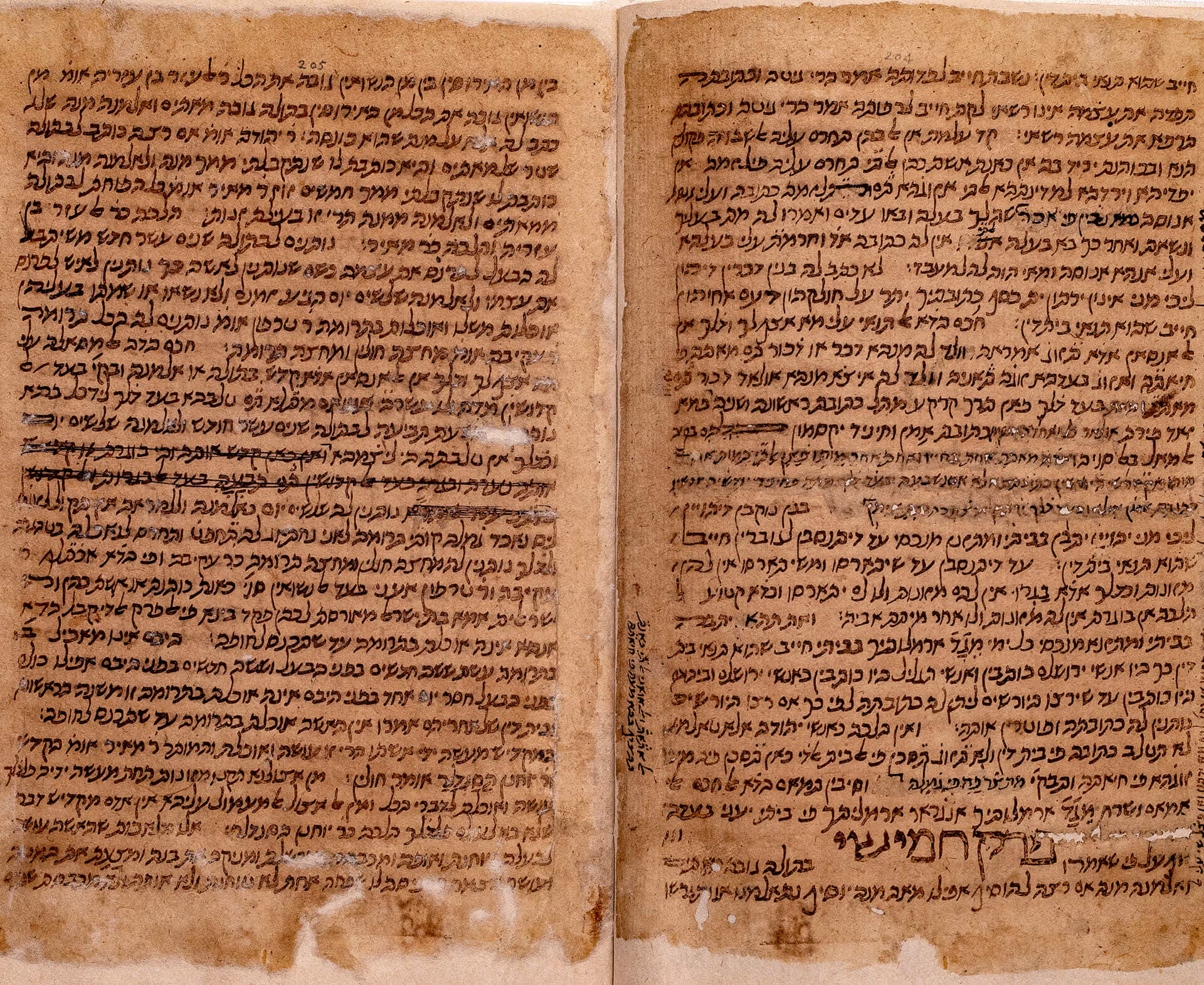

This work, one of the most important commentaries on the Mishnah, was written with the objective of clarifying the complexities of the Talmud and presenting the relevant halakhic decision for each section of the Mishnah. This was Maimonides’ own working copy in which he made changes and corrections throughout his life ever since beginning work on it at age 23. The work is written in Judeo-Arabic and includes explanations, halakhic decisions, and the author’s own reflections on theological issues.

This work by Moses Maimonides is the greatest individual achievement in the field of halakha and Rabbinic literature, including halakhic rulings covering every aspect of Jewish life. Due to its status as a foundational text, it was sometimes copied in the form of a monumental codex, similar to the Bibles of the period. The illustrations were added in the early 15th century, and closely follow the halakhic topics dealt with in the text.

Rabbi Yosef Caro, author of the Shulḥan ʿArukh, was one of the greatest halakhic decisors, who played a part in determining the Jewish way of life according to Jewish law that is still influential today. The ruling shown here concerns the inheritance of the orphan Rachel bat Shmuel Villalobos of Istanbul. The document was not written by Caro himself, but bears his signature.

The first printed edition of this work, written in Safed in 1563. After its publication, the work was distributed rapidly and was so successful that it became the most authoritative work determining the way of life of observant Jews up to the present day.

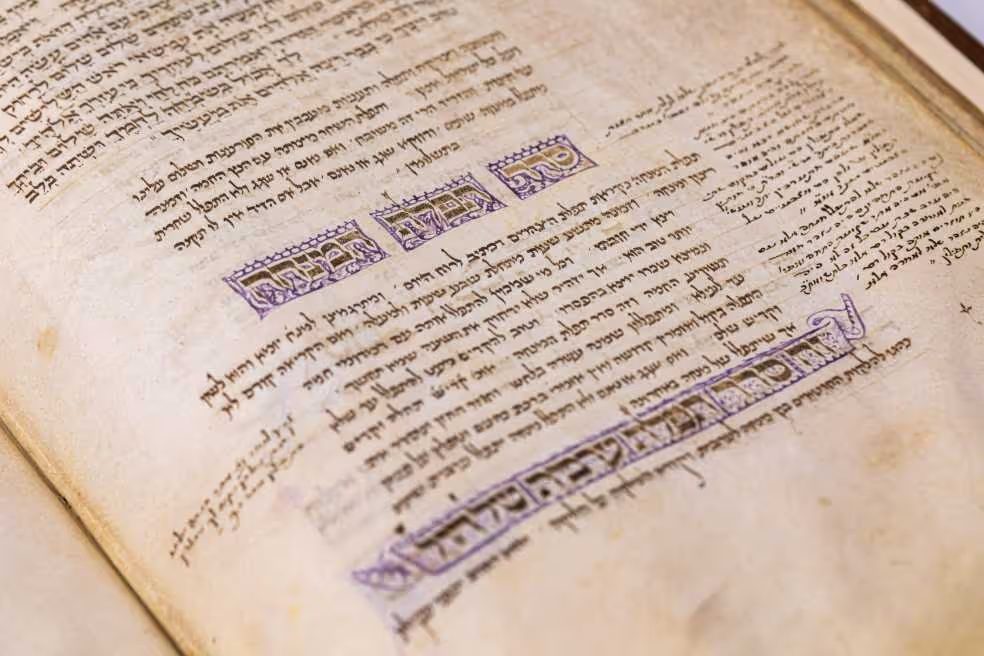

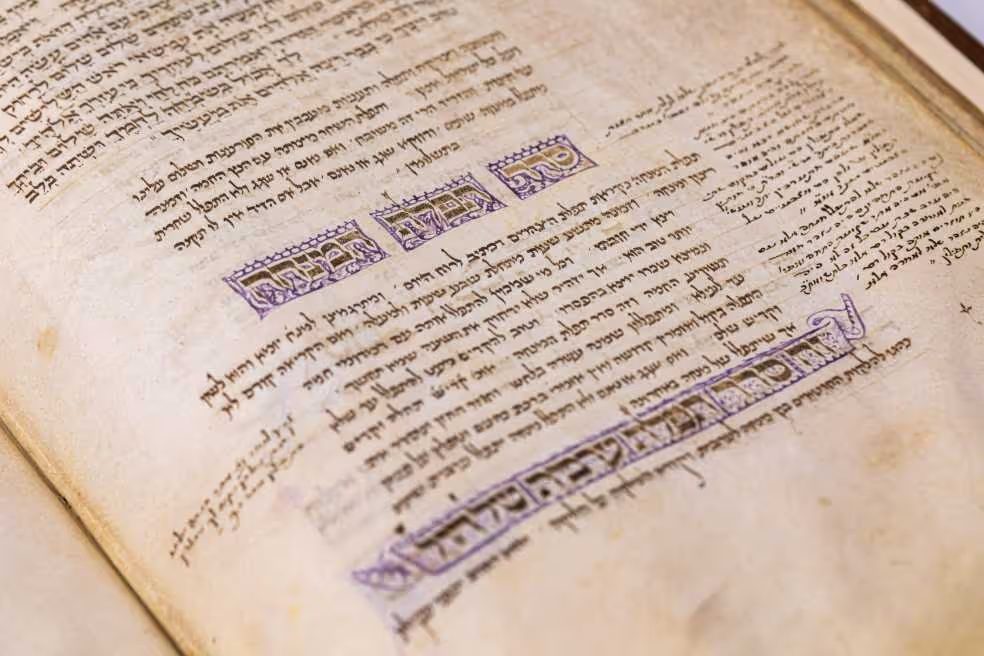

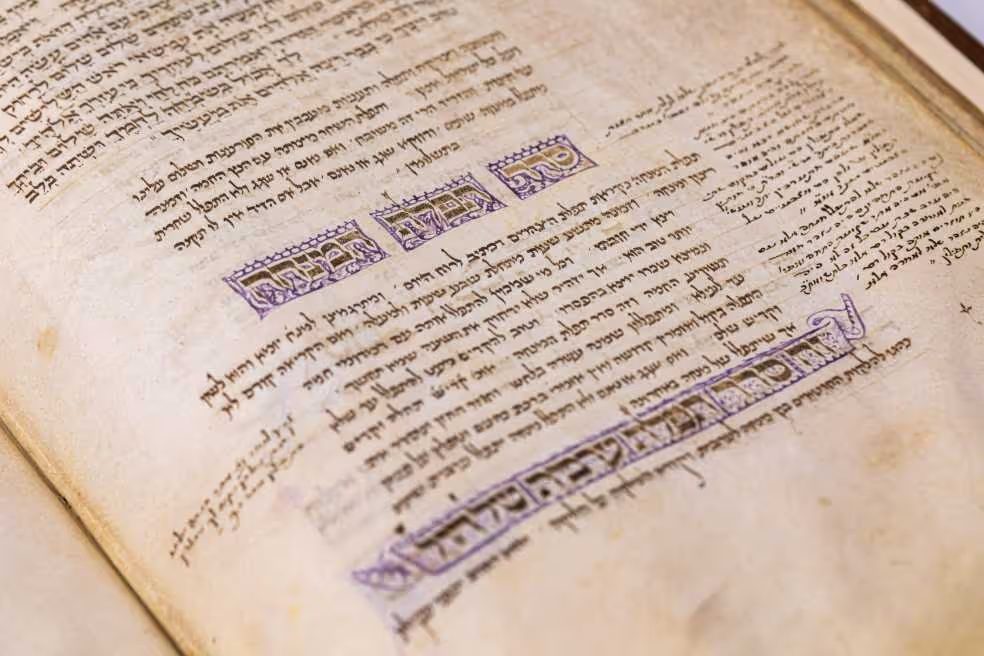

The manuscript is decorated with color and gold ornamentations and pen-and-ink drawings in a style often found in manuscripts from Lisbon. The basic customs of prayer established among Spanish Jews were fixed and stable, but there was a large variety of extensions to the prayerbook, including liturgical poetry in Hebrew. The important poets of the Golden Age in Spain composed piyyutim (liturgical poems) for many parts of the prayers, and different communities selected extracts from them, as seen in the prayerbook here.

This manuscript is one of the most beautiful festival prayerbooks, containing one of the richest collections of liturgical poems. Another unique feature is the impressive ink drawings made by one of the most important and talented copyists and illustrators of Jewish manuscripts, who was active in Germany and later moved to Italy. The decorations feature real and imaginary animals, such as a unicorn.

The Zohar, the most important work in the history of Jewish mysticism and the basis of all later kabbalistic teachings, includes a commentary on the symbolic and mystical aspects of the Torah. Isolated sections of the work began to appear in manuscript form in Spain at the end of the 13th century. Its printing and publication contributed to it being seen as a unified work and to its centrality and influence. This copy of the first printed edition of the Zohar was apparently used by Rabbi Yitzhak Luria (“the Ari”) the great kabbalist of Safed, and his disciples.

Sefer Yeṣira is an ancient Hebrew text, enigmatic and magical. It deals with the spiritual structure of the world and the profound meanings of the Hebrew letters through which the world was created.

The copy shown here was the property of the great scholar of Jewish mysticism, Gershom Scholem. His own handwritten notes can be seen on the pages. The artist Micha Ullman, whose sculpture “Letters of Light” is exhibited in the Library garden, was also inspired by Sefer Yeṣira.

Sefer Yeṣira is an ancient Hebrew text, enigmatic and magical. It deals with the spiritual structure of the world and the profound meanings of the Hebrew letters through which the world was created. The artist Micha Ullman, whose sculpture “Letters of Light” is exhibited in the Library garden, was also inspired by Sefer Yeṣira.

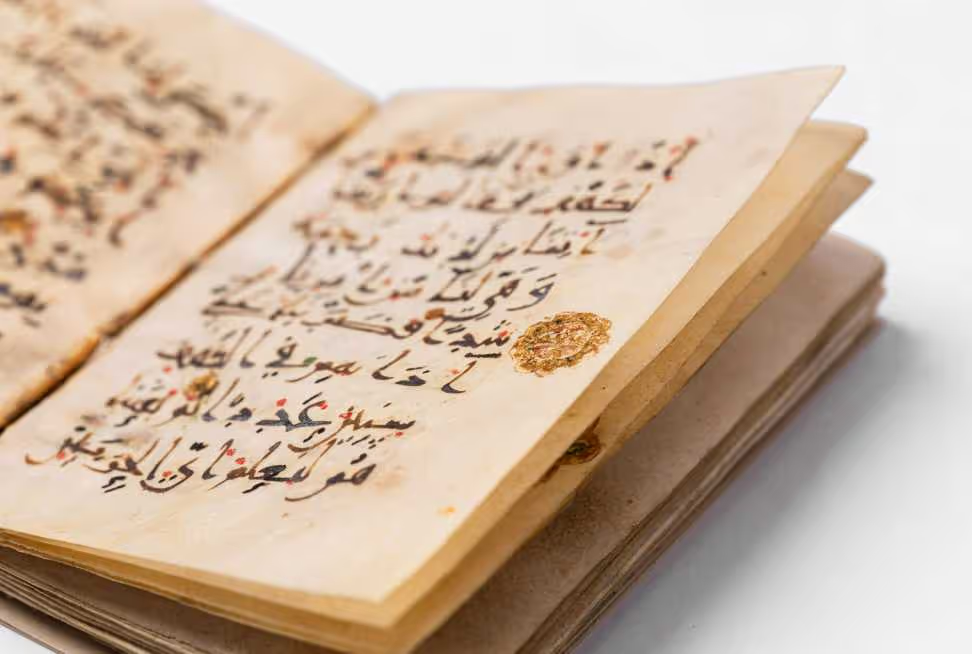

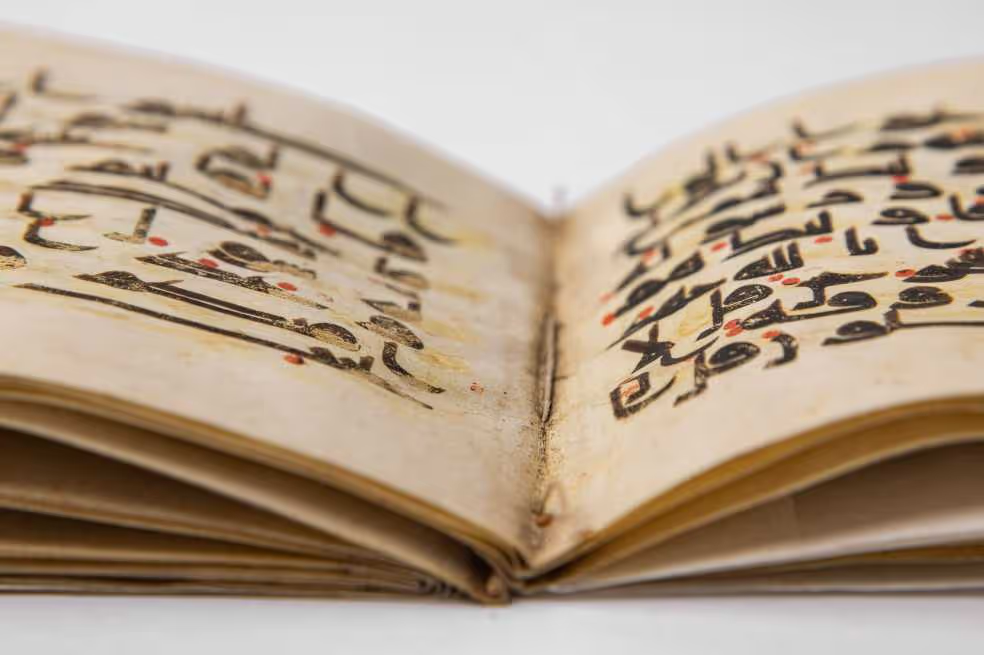

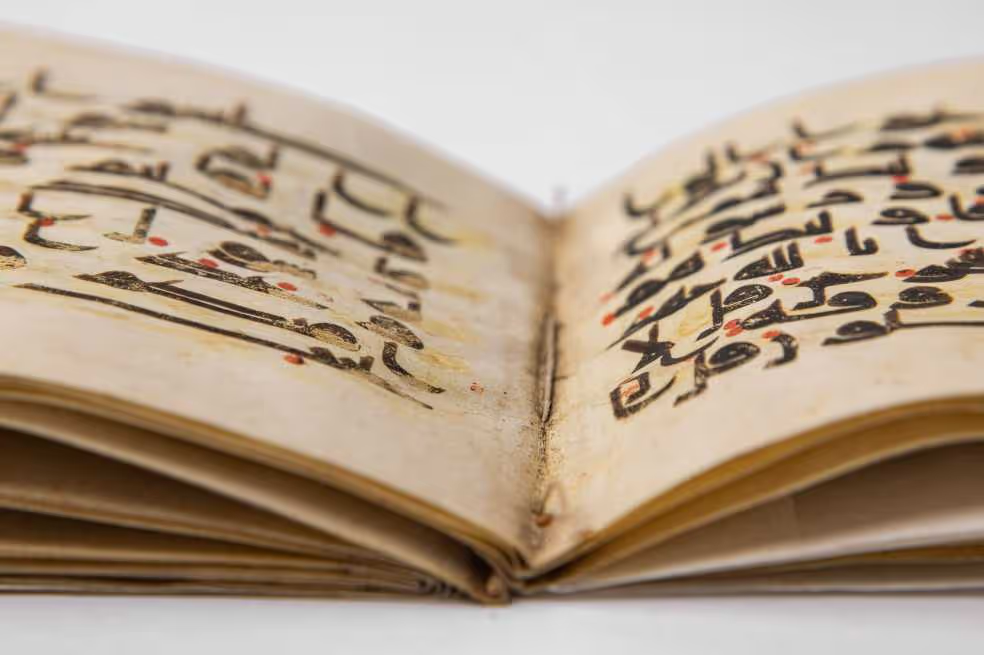

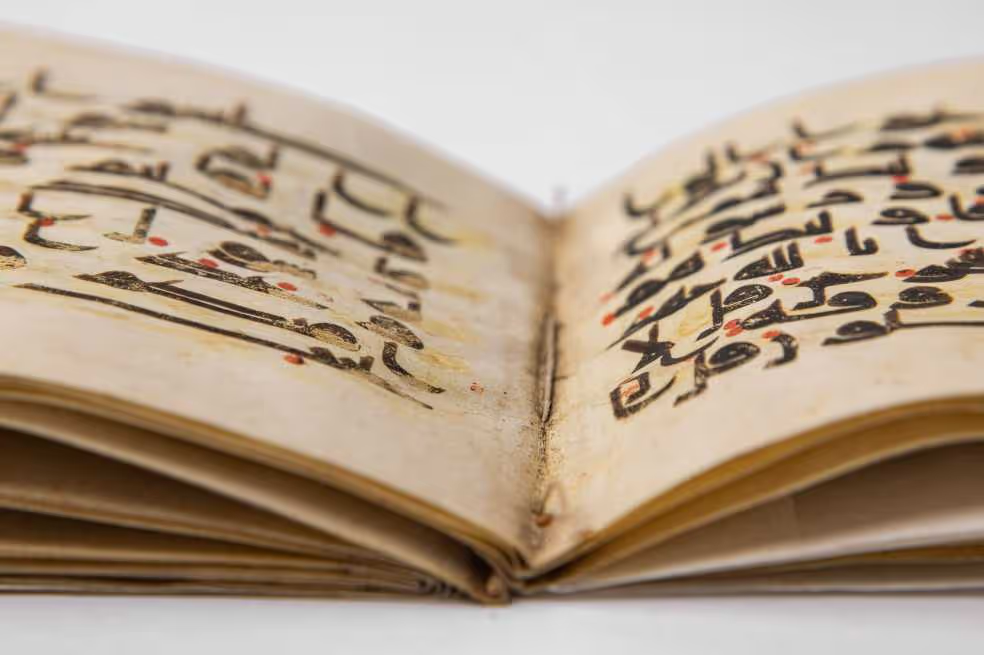

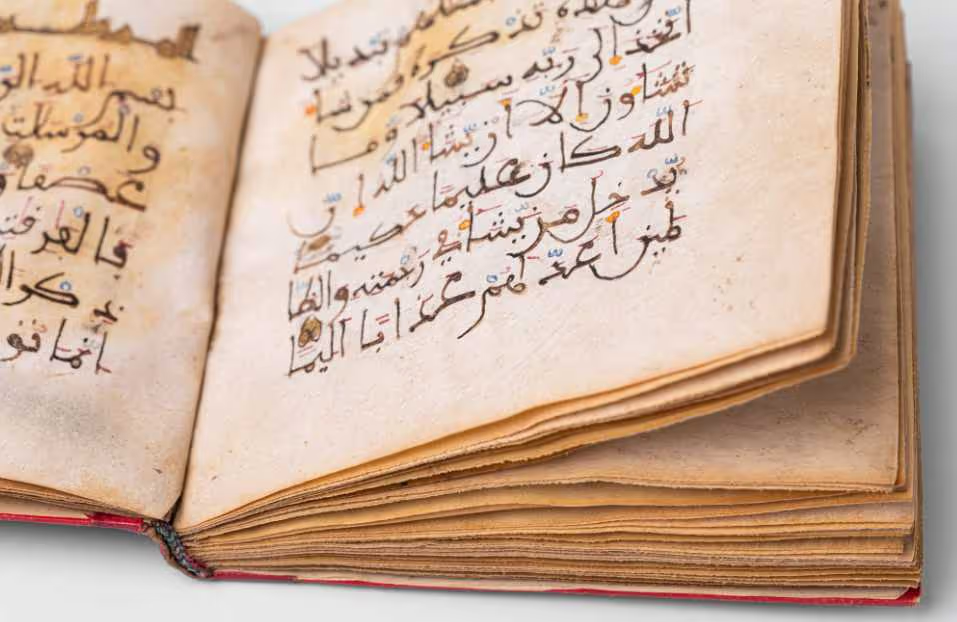

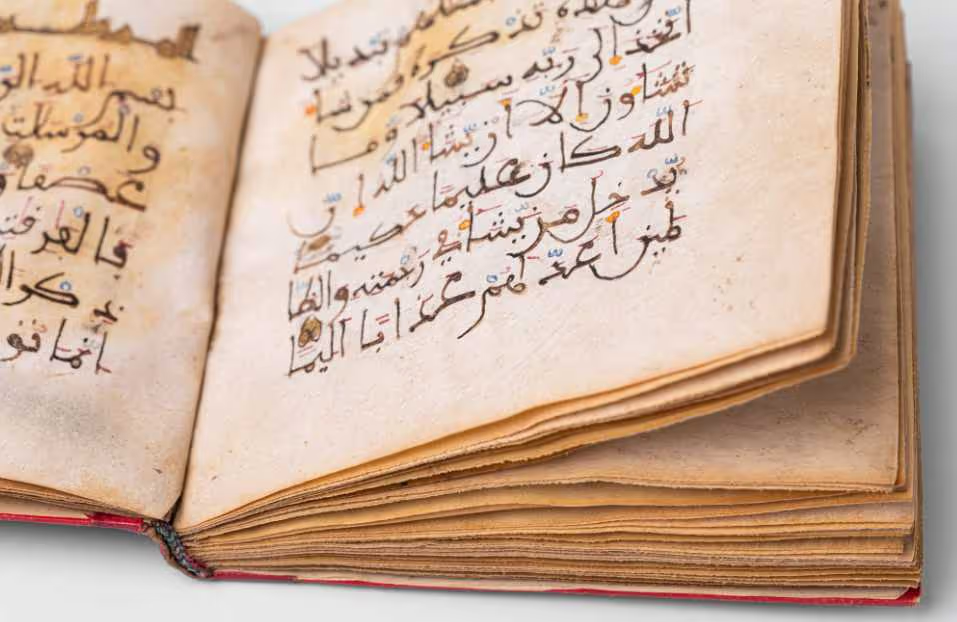

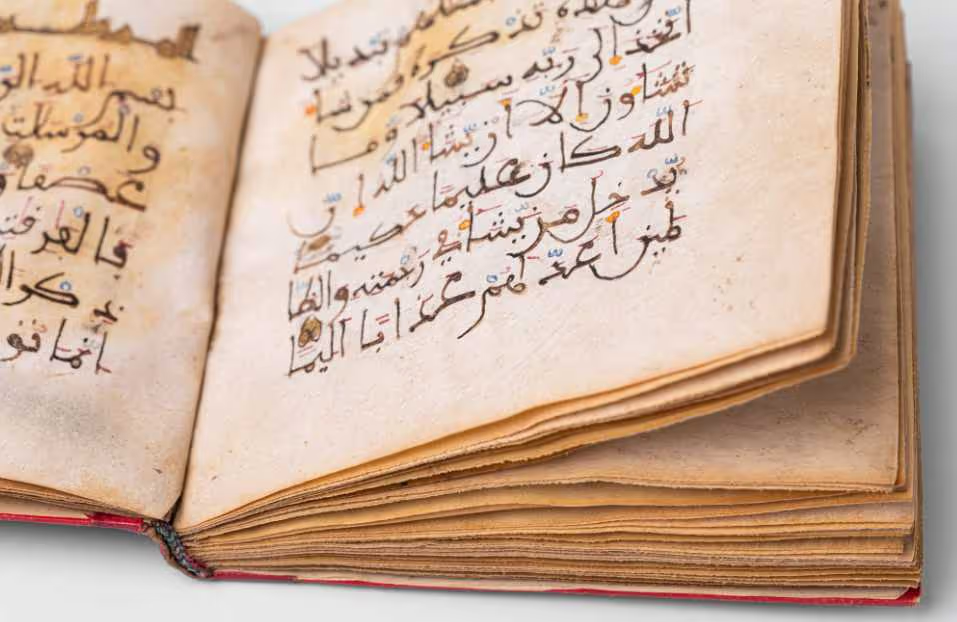

According to Muslim belief, the Quran is the word of God that was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. It is the central text for Muslim religion and life, spiritual inspiration, and Muslim prayer and ritual. This 9th-century copy of a Quran section is written in the Kufic script. Aside from the geometrical and proportional script style, Qurans from this period are also distinguished by their unique format, wider than they are tall. This unique format may have been chosen to distinguish the Quran from other books, marking it as the word of God.

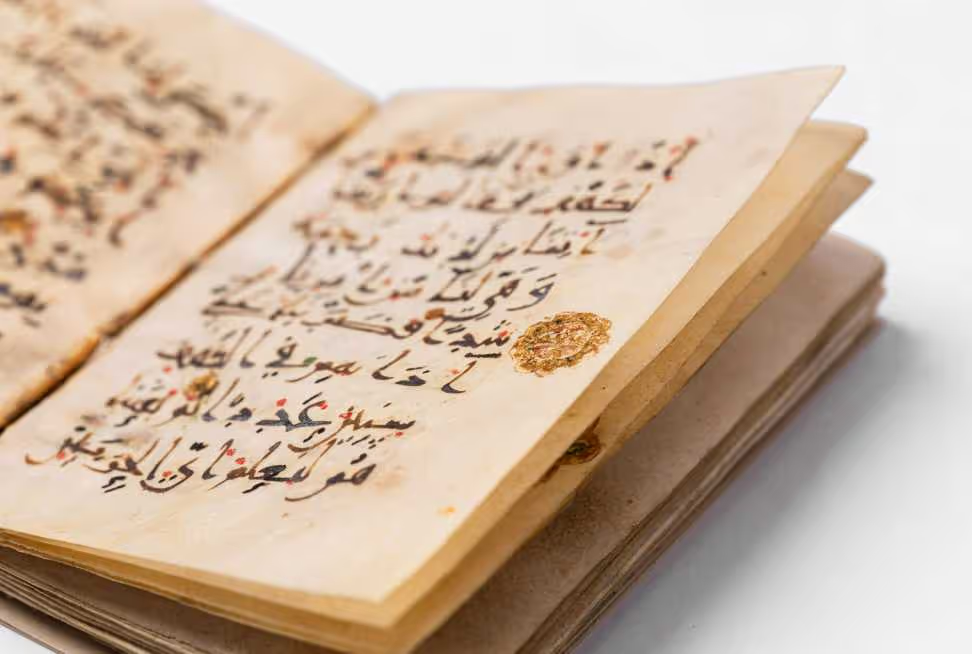

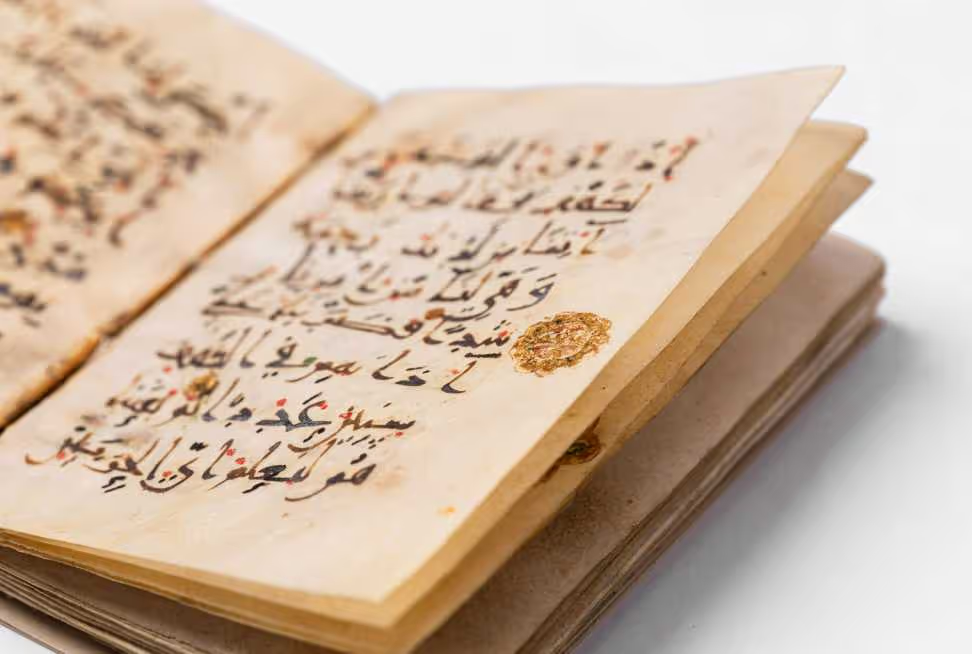

According to Muslim belief, the Quran is the word of God that was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. It is the central text for Muslim religion and life, spiritual inspiration, and Muslim prayer and ritual. This medieval illuminated Quran was likely copied by a student of the famous Baghdadi calligrapher Ibn al-Bawwāb (d. 1022). The margins preserve instructions for reciting the text and include a color-coded system of seven parallel styles of pronunciation, known as the “readings” (qirā’āt). The manuscript exemplifies the role of Quran recitation in Muslim devotional life.

According to Muslim belief, the Quran is the word of God that was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. It is the central guide for Muslim religion and life, spiritual inspiration, and Muslim prayer and ritual. This 9th-century copy of the Quran captures a transitional moment in the history of Arabic writing. Early manuscripts either did not indicate vowels at all or employed colored dots. This Quran was originally written using the dot system, but a later copyist, named al-Khayqānī, “modernized” the text by adding the diacritical signs that we recognize today.

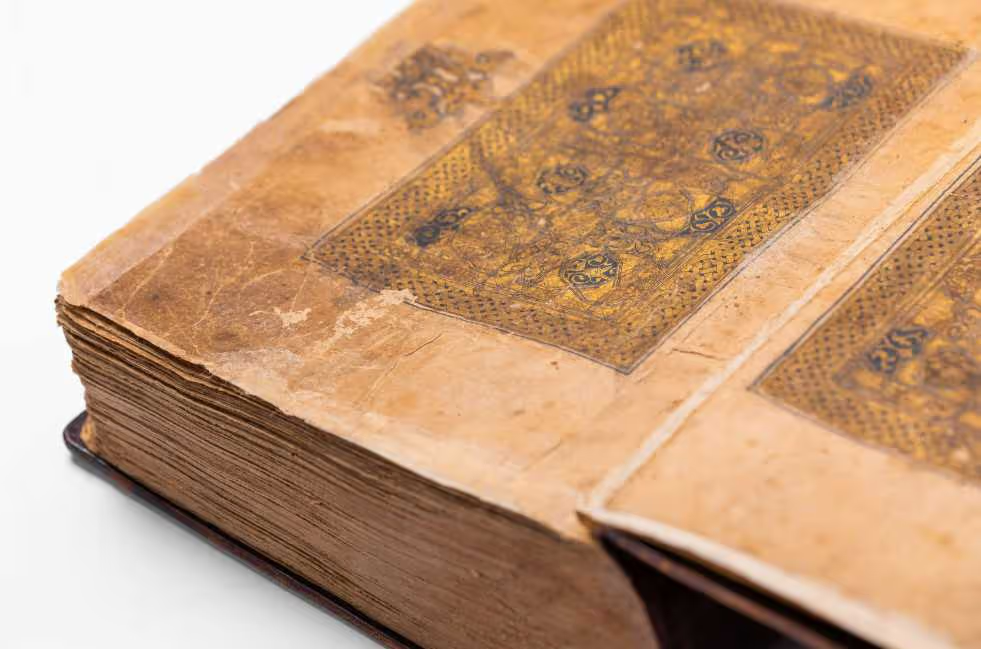

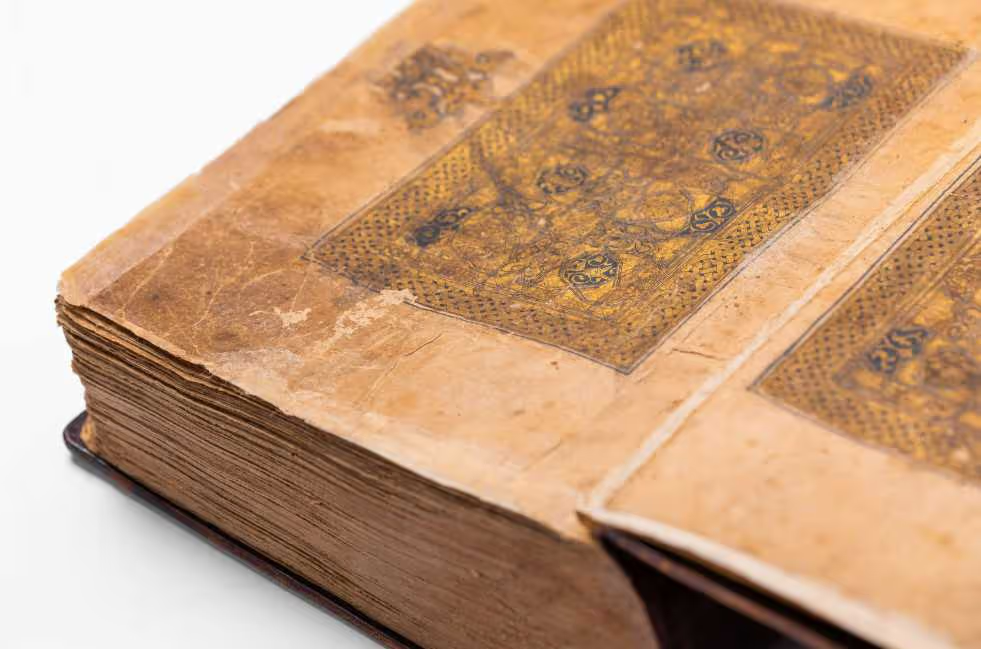

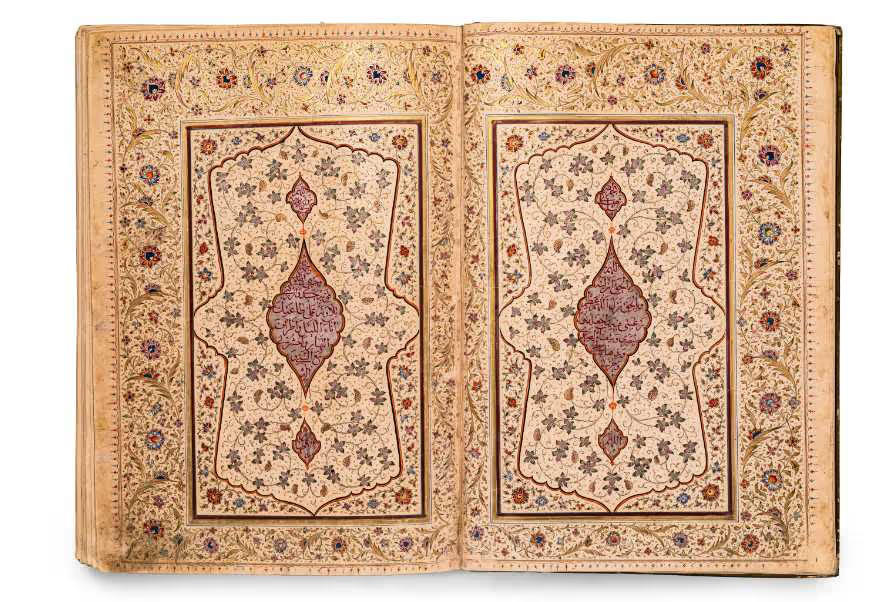

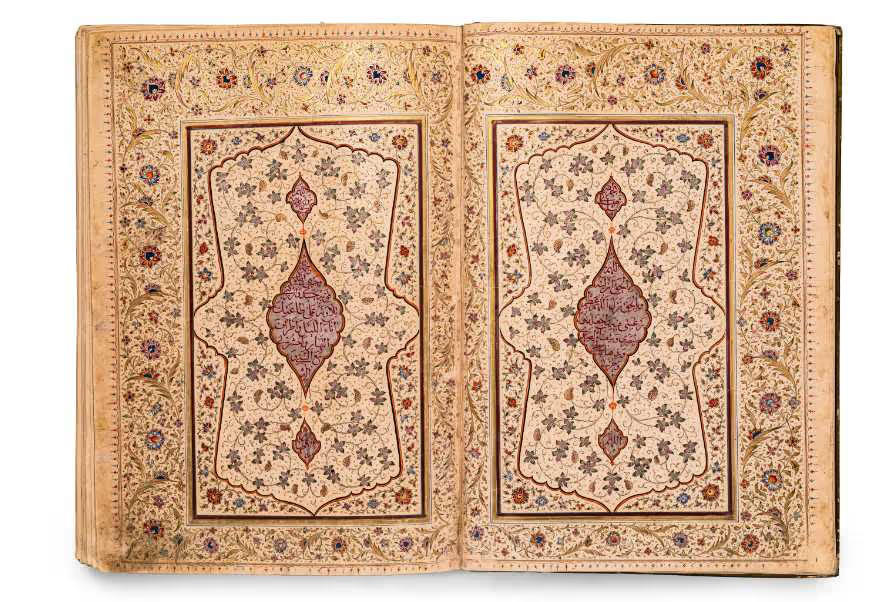

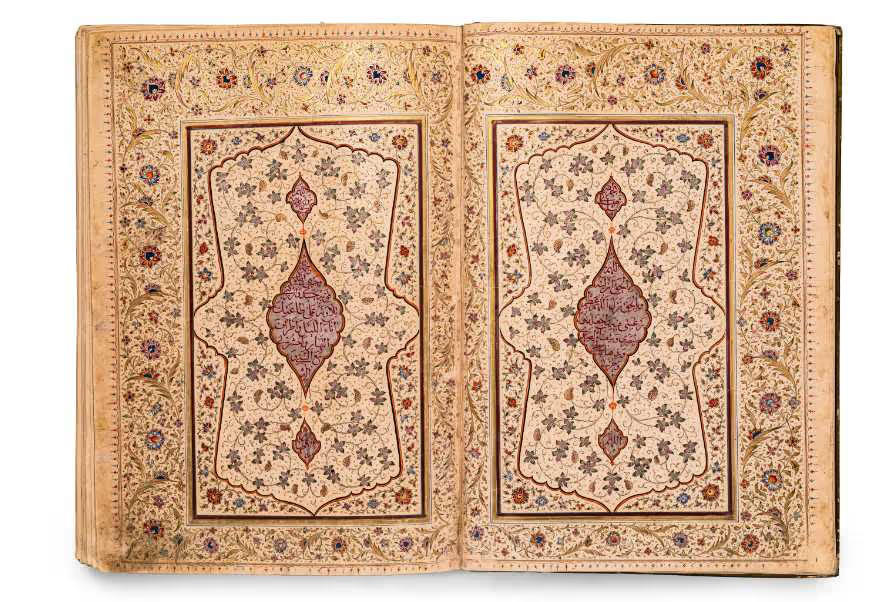

This magnificently illuminated and gilded Quran was produced in Iran in the prestigious Shirazi style. The ornamental seals on the first pages of the Quran of Ottoman Sultans Selim I (d. 1520) and Mustafa I (d. 1622) indicate that it was later incorporated into the royal Ottoman library.

This illuminated Quran includes an interlinear translation of the original Arabic text, in black, to Persian, in red. The Quran refers numerous times to Arabic as the language of God’s revelation, and Arabic remains the central devotional language for Quran recitation and prayer. Nevertheless, the majority of Muslims today are non-Arabic speakers. The inclusion of a Persian translation in the Quran text is a sign of Islam’s transformation from an Arab religion to a global multi-lingual one.

This beautifully illuminated copy of the Quran was produced at a time when the art of printing was already widespread in Iran. The manuscript also includes an interlinear translation of the original Arabic text, in black, to Persian, in red. The Quran refers numerous times to Arabic as the language of God’s revelation, and Arabic remains the central devotional language for Quran recitation and prayer. The inclusion of a Persian translation in the Quran text is a sign of Islam’s transformation from an Arab religion to a global multi-lingual one.

Ibn Sīnā, known in Europe as Avicenna, was the most illustrious physician and philosopher of the Islamic Middle Ages. An 11th-century copy of the first portion of his Book of Healing which can be seen here, reworks the Aristotelian tradition to present a comprehensive account of reality and a guide for life.

![תיקון [ספר] האופטיקה, אדירנה, 1511](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/64e1c4e63df2a4e609a0291f/659ba54cee05a2448ac3751d_C6_29c%20%D7%AA%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%9F%20%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%A8%20%D7%94%D7%90%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%94.avif)

![תיקון [ספר] האופטיקה, אדירנה, 1511](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/64e1c4e63df2a4e609a0291f/659ba54cee05a2448ac3751d_C6_29c%20%D7%AA%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%9F%20%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%A8%20%D7%94%D7%90%D7%95%D7%A4%D7%98%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%94.avif)

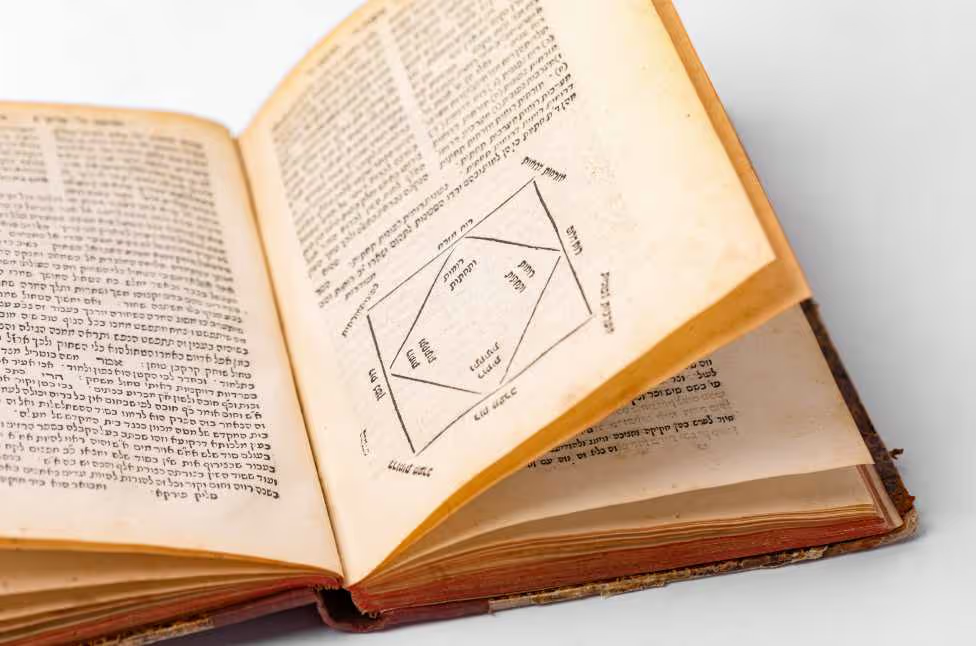

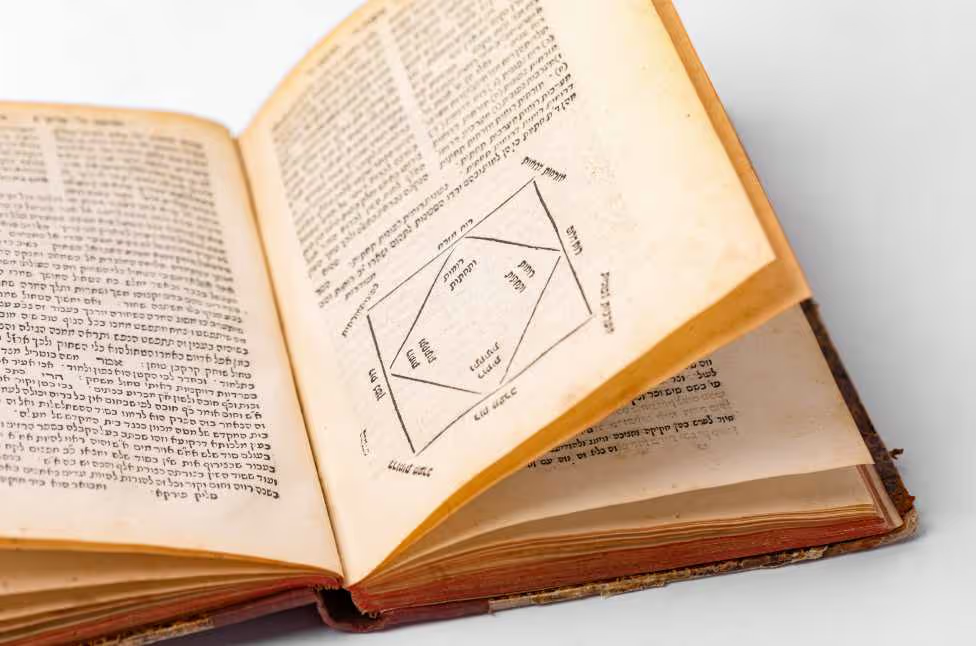

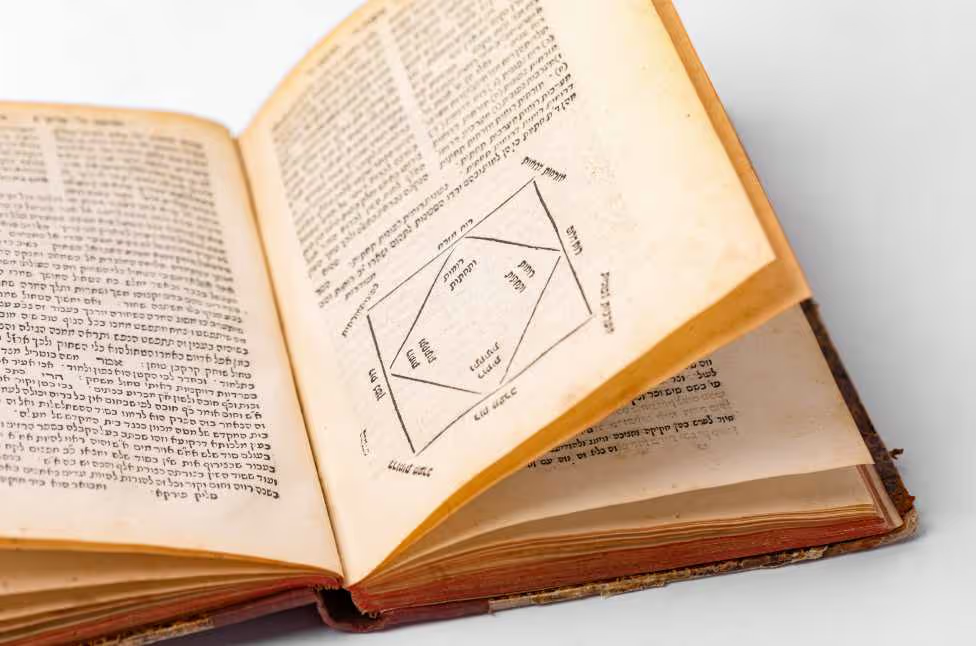

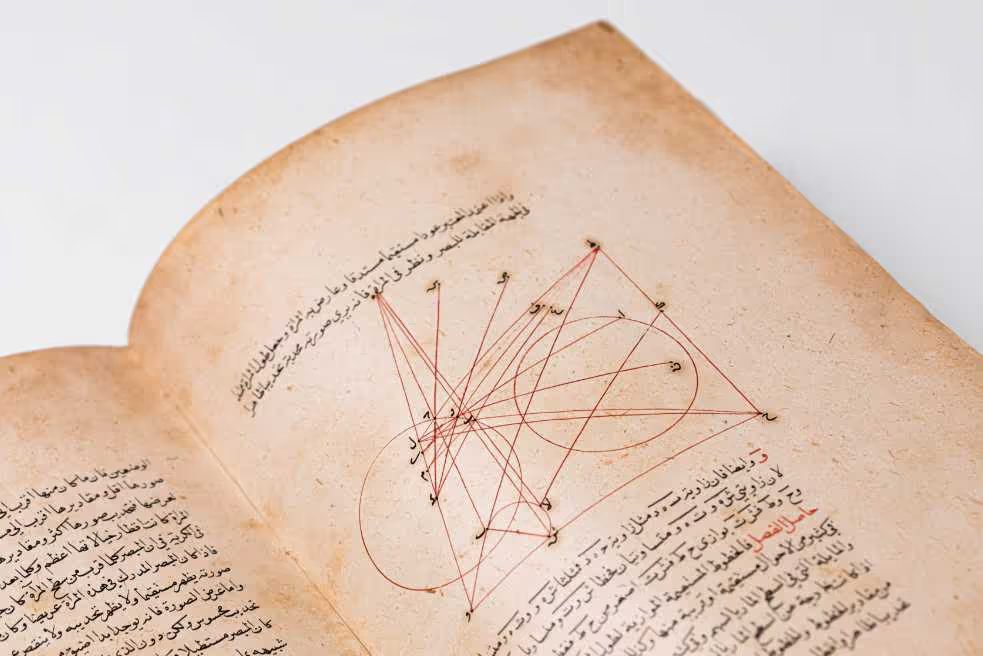

The 10th-century scientist Ibn al-Haytham was known as “the father of optics,” and his groundbreaking Book of Optics was the first treatise to explain fully how the eye functioned. Shown here is Kamāl al-Din Fārisi’s Revision of the [Book of] Optics, in which the 13th-century Persian scientist explains how our eyes see color and how a rainbow works.

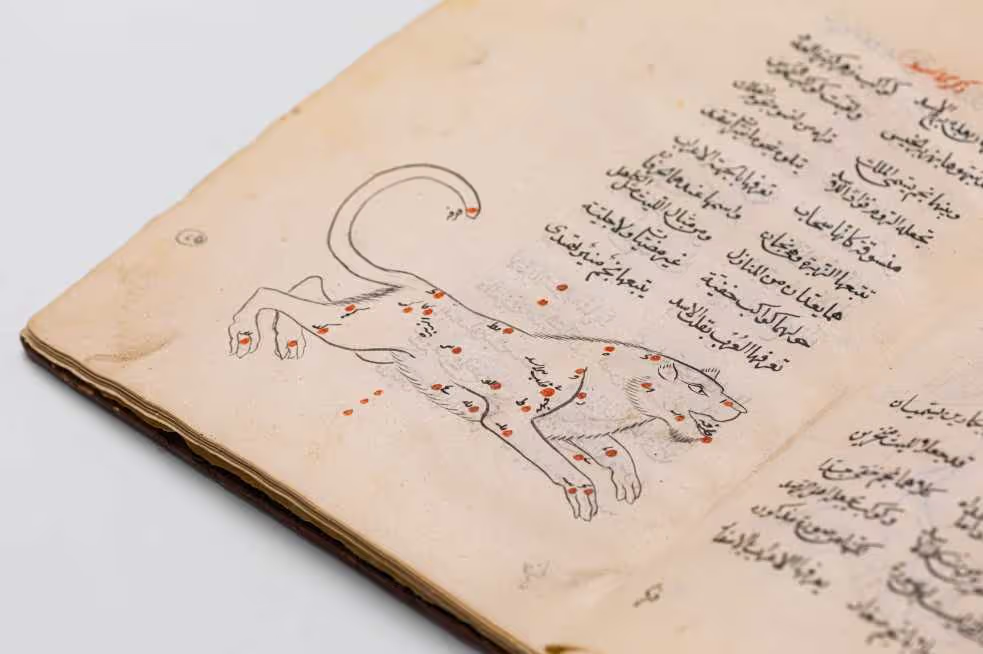

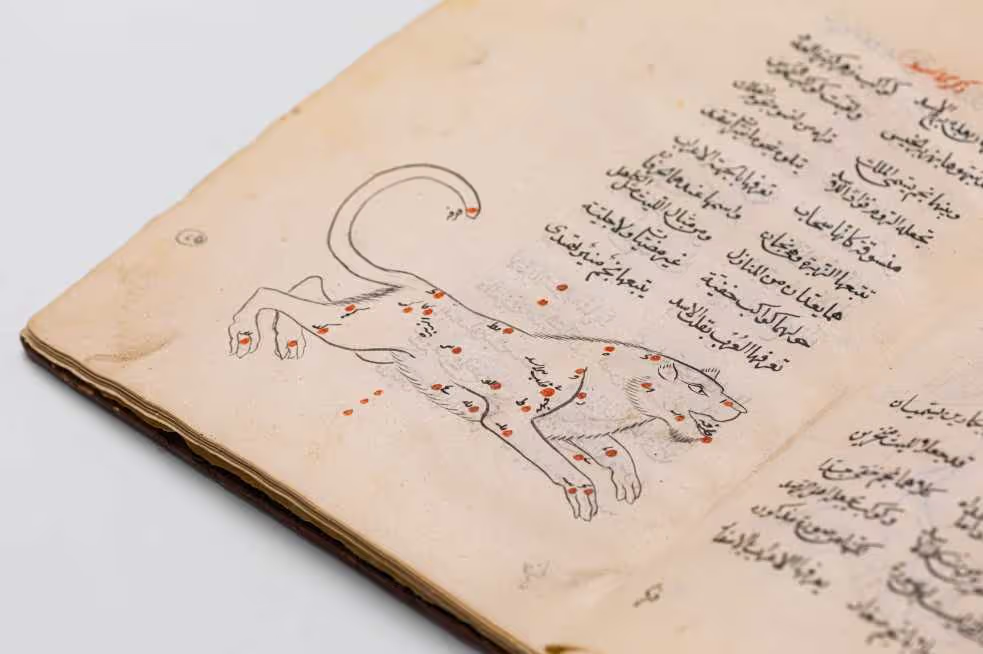

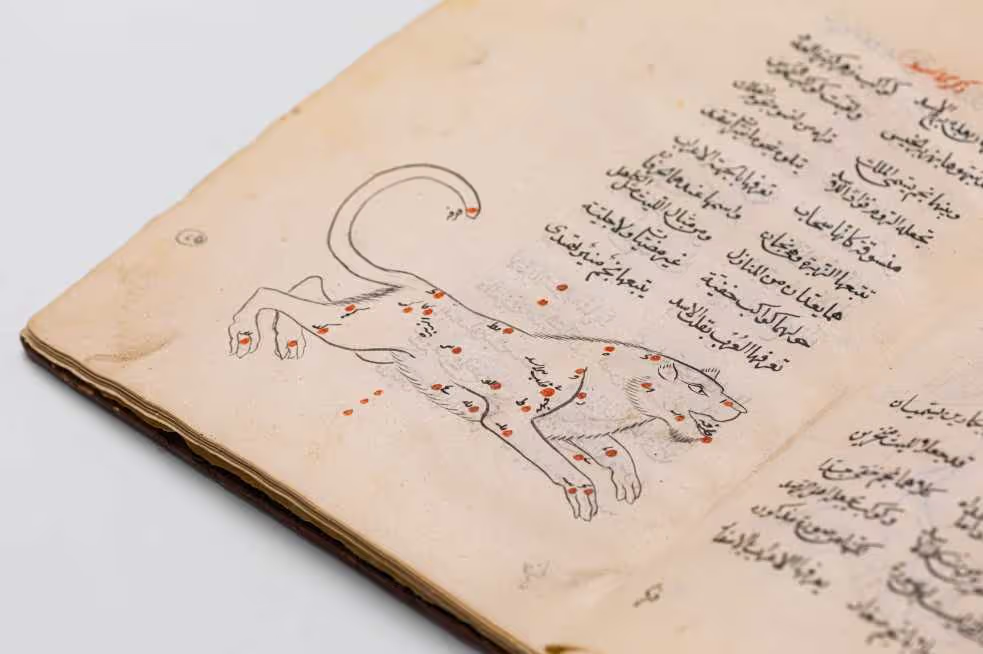

The popular work The Shape of the Fixed Stars, composed by ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī (d. 986), combines descriptions of the constellations according to the Arabian system of anwāʿ, seasonal reckonings based roughly on the zodiac, and Ptolemaic astronomy. This version is a verse epitome of the original work composed by al-Ṣūfī’s son Abū ʿAlī.

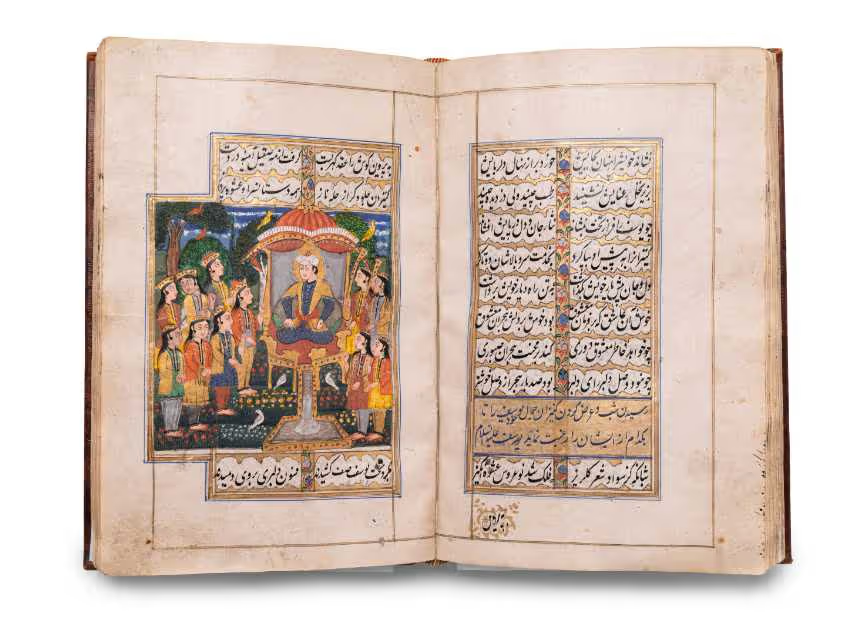

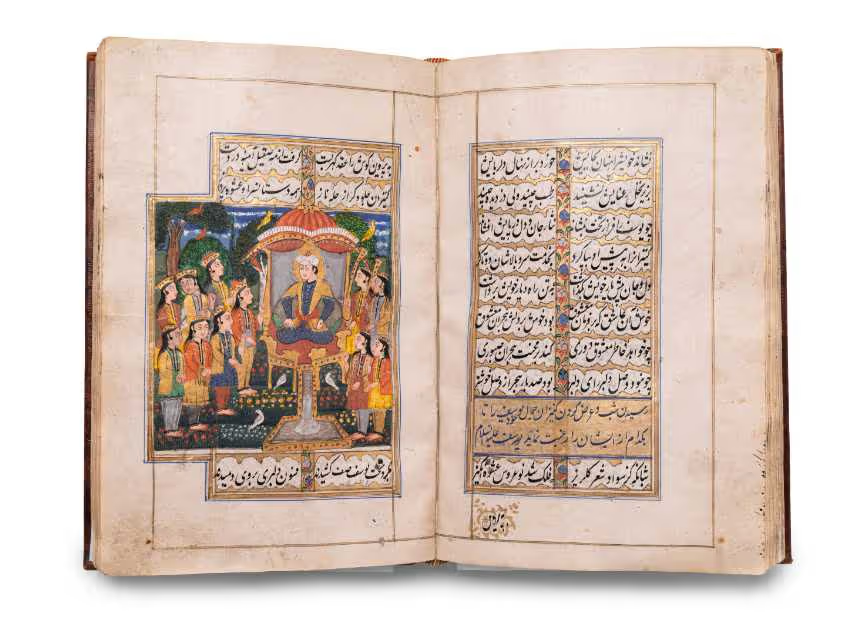

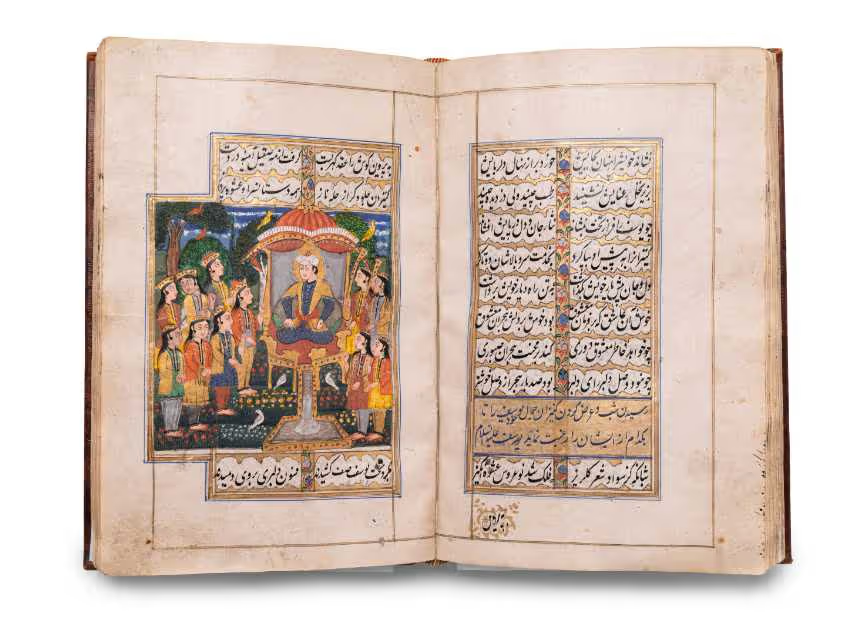

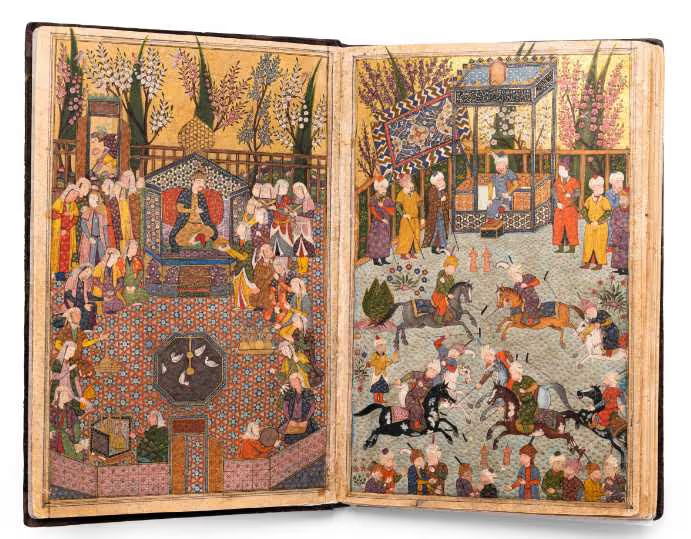

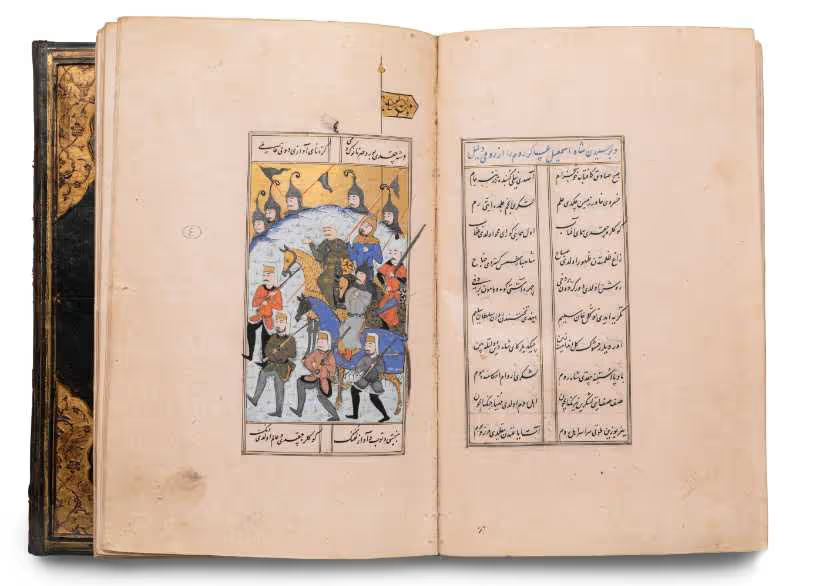

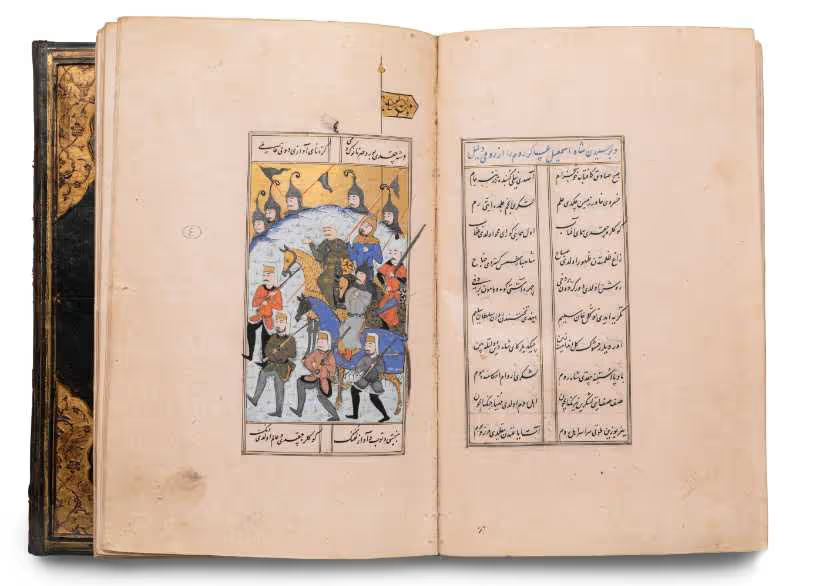

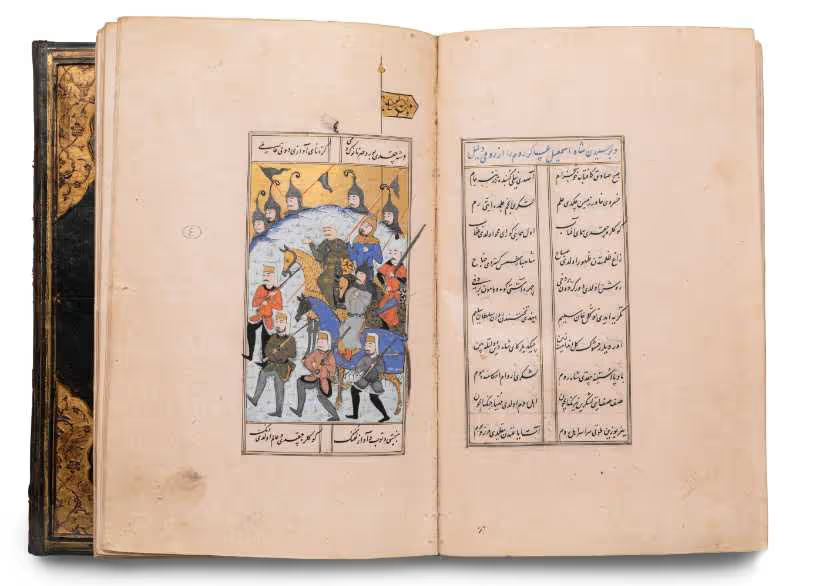

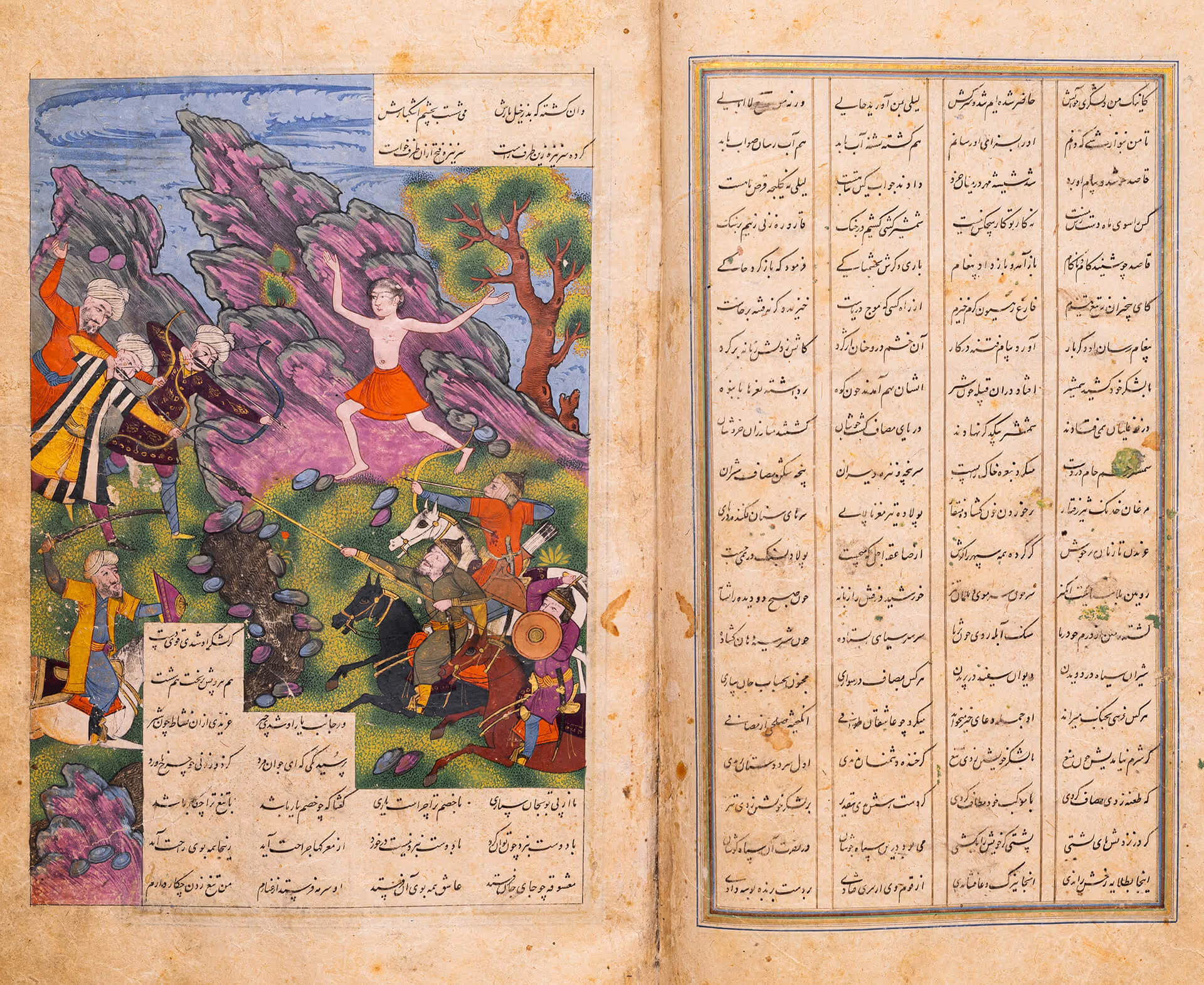

Rūmī’s landmark work is the greatest Sufi poem ever written, and one of the crowning achievements of Persian culture. The work is celebrated for its enlightening discourses and entertaining stories, touching on the lives of prophets, kings and saints, on the one hand, and animals, servants and paupers, on the other.

Al-Ghazālī was one of the most prominent and influential Muslim thinkers of all time. He was a famous scholar and official in Baghdad when he renounced his worldly position to devote himself to spiritual pursuits. This handwritten copy of Ghazālī’s commentary on the Quranic chapter of light, Sūrat al-Nūr, is remarkable for the clarity of its writing.

The Islamic scientific tradition began under the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), when Classical works were first made available in Arabic. The tradition continued to develop in Arabic, Persian, and, as in this important 16th-century work, in Ottoman Turkish.

The Muslim tradition developed narratives about Yūsuf, the Arabic name for the biblical prophet Joseph. These narratives expand the role of Yūsuf’s Egyptian master’s wife, known as Zulaykhā. Beginning as a wicked temptress, she transforms into a sympathetically besotted woman who ultimately confesses her crime and fully repents.

Kufic script, which probably originated in Kufa (modern Iraq), is considered the oldest Arabic calligraphic style. It was used primarily for writing Qurans on parchment; later it became a decorative script still in use today. As seen in the 9th-century Quran fragment displayed here, the Kufic script is typified by the geometric regularity and proportionality of letter forms, lines and the text block as a whole.

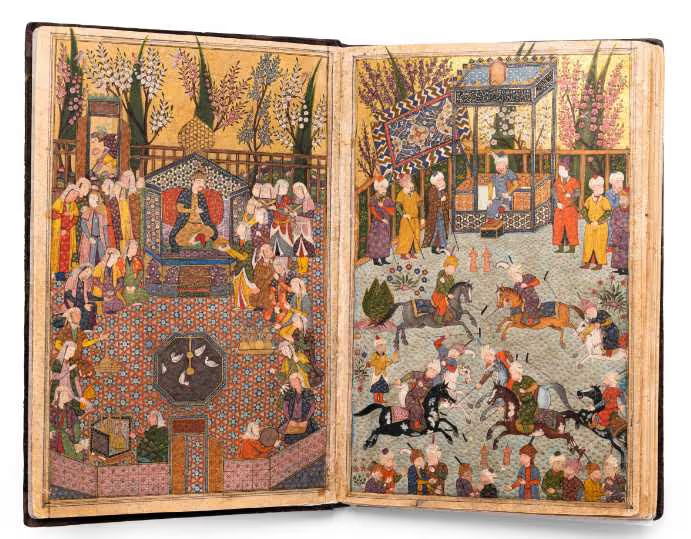

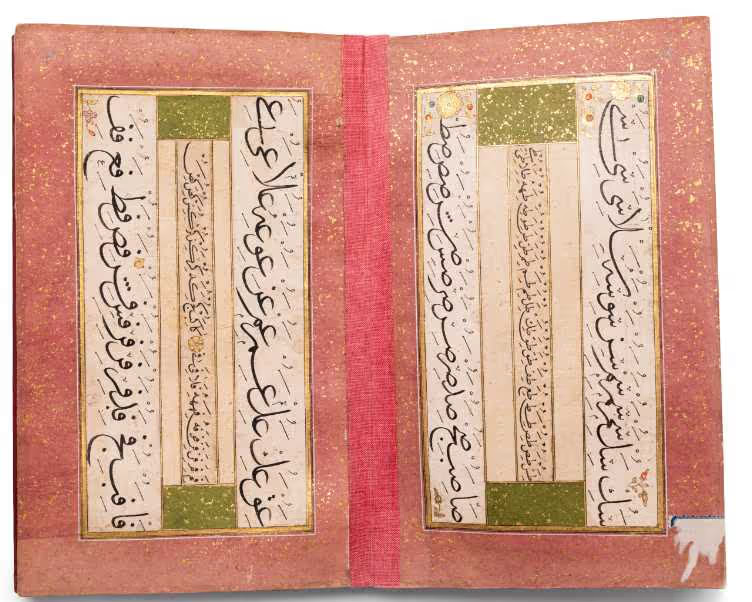

This rare and precious manuscript, written in the lifetime of the author, is an example of the nastaʿlīq script developed by Persian scribes and employed especially for poetry. Known as “the bride of Islamic calligraphy,” nastaʿlīq is typified by final letters extending to the lower left of the line.

Kufic script, which probably originated in Kufa (modern Iraq), is considered the oldest Arabic calligraphic style. It was used primarily for writing Qurans on parchment; later it became a decorative script still in use today. As seen in the 9th-century Quran fragment displayed here, the Kufic script is typified by the geometric regularity and proportionality of letter forms, lines and the text block as a whole.

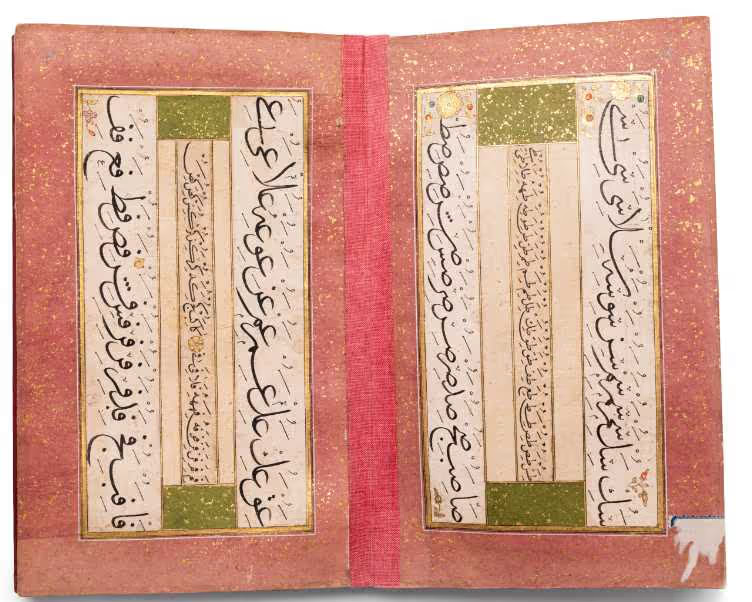

Albums such as this, known as Mufrādāt, were used to demonstrate the letters of the Arabic alphabet, in isolation and in the various combinations, in two scripts. The upper and lower lines are in thuluth, a decorative script often used for headings and epigraphy. The middle lines are in naskh. These albums were compiled both by students as part of their training, and also by master scribes as exemplars of correct calligraphic style.

North African scribes wrote in a unique script, ultimately derived from Kufic, distinct from the scripts of the Levant, Mesopotamia and Islamic East. This illuminated copy exemplifies the typical features of maghribī (North African) script, including final alif being drawn from top to bottom; small, left-leaning extensions at the top point of the letters alif, lām, ṭāʾ, and ẓāʾ; and the letters fāʾ written with a dot below and qāf written with only one dot above. Chapter titles are written in gilded Kufic script.

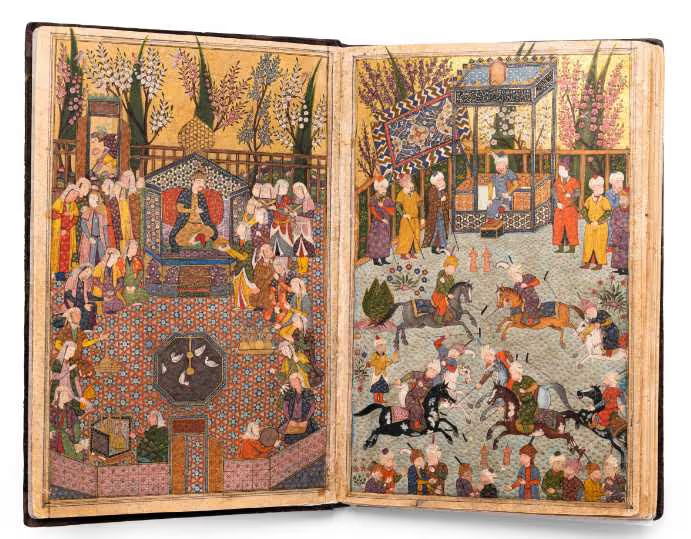

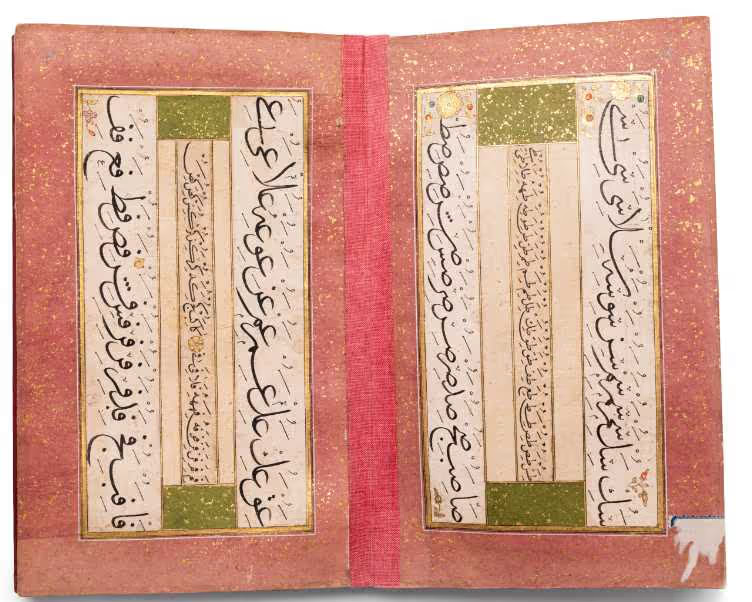

The fluid and artistic nastaʿlīq script, developed originally in Iran, also served for poetic works in writing traditions particularly influenced by Persian, including Kurdish, Turkish and Urdu. This decorated royal manuscript of the collected Persian and Turkish poems of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I was produced during the lifetime of the author.

The fluid and artistic nastaʿlīq script, developed originally in Iran, also served for poetic works in writing traditions particularly influenced by Persian, including Kurdish, Turkish and Urdu. This illustrated royal manuscript describes the conquests of the Ottoman Sultan Selim I (r. 1512–1520) and was copied four years after his death. The work was commissioned by Selim’s son, Suleiman the Magnificent.

Copies of a single weekly Torah portion are rare, possibly influenced by the practice of copying single suras of the Quran. The decoration in the style of contemporary oriental Quran manuscripts is also evidence of local influence.

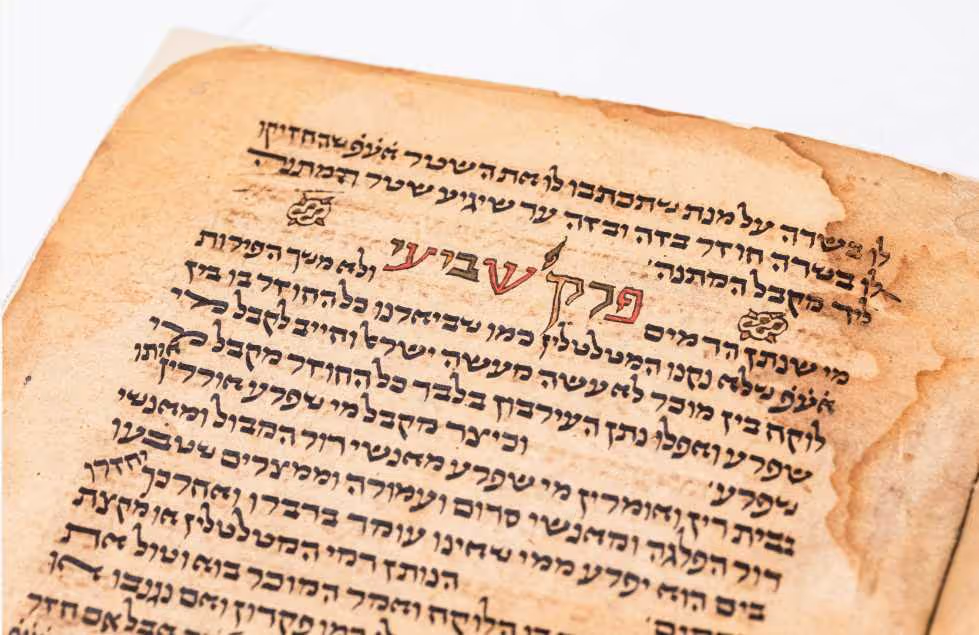

“Oriental script” is one of the scripts belonging to the Islamic branch of Hebrew script. The script was prevalent in the medieval period in Egypt, the Land of Israel, Syria and Lebanon, and also in Iraq, Iran and Uzbekistan in central Asia. The use of a reed pen gives homogenous line widths, with no great difference between vertical and horizontal strokes. The roofs of the letters are characterized by serifs and prominent crowns. The height and width of square script letters are the same and the vertical lines are perpendicular to the base.

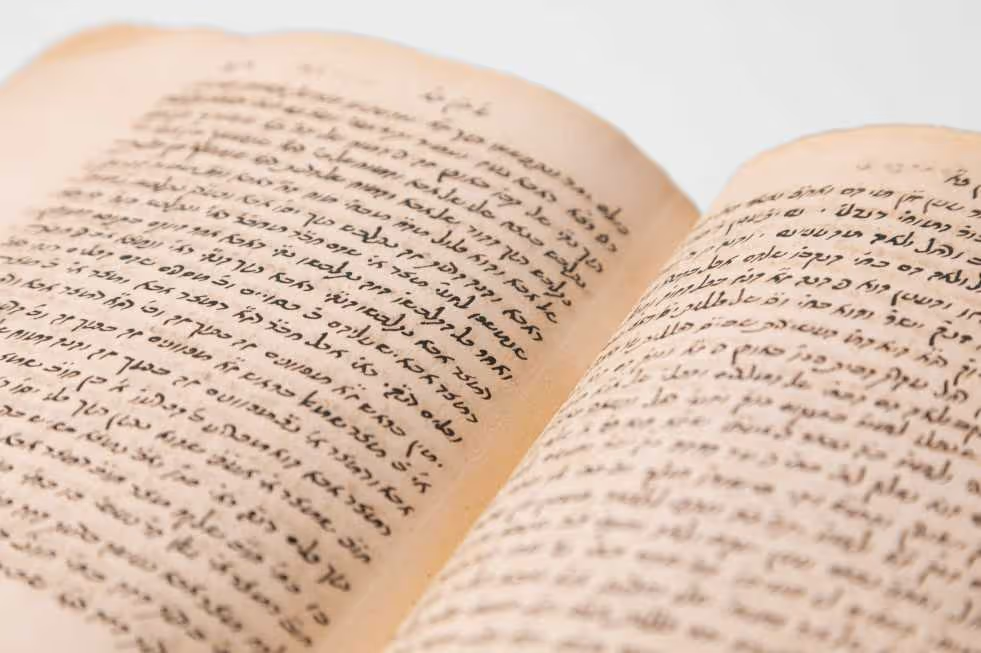

This work is based on a book of customs practiced in the communities of France and Germany, with additional notes by Rabbi Avraham Klausner. It was copied in Ashkenazi semi-cursive script shortly after Klausner’s death.

“Ashkenazi script” belongs to the Christian family of Hebrew scripts, prevalent in the medieval period in Western and Eastern Europe. It is written with a quill pen which permits the formation of subtle elements and ornamental decorations of the letter strokes. “Semi-cursive” script is halfway between square and cursive script. It is more tightly written than square script and its letters, including their internal spaces, are smaller and more compact. The curved and ornate lines of the letters are made up of gentle strokes.

Yemenite Jews were great admirers of Maimonides and still depend on his works for halakhic rulings. Their copies of his Mishneh Torah preserve a unique text, which Yemenites claim represents Maimonides’ final opinion.

“Yemenite script,” still used by traditional Yemenite Jews, is a variety of “Oriental script,” differing from it chiefly in broader strokes, fewer serifs on the roofs of the letters and a greater distinction between horizontal and vertical strokes.

The kabbalist Rabbi Haim Vital (Safed 1542 – Damascus 1620) was the leading pupil of Rabbi Yitzhak Luria (“the Ari”) for two years, and his works are the main source for Luria’s teachings. The rapid dissemination of his writings on the Ari’s mystical doctrine completely transformed the world of Jewish mysticism. The style of writing in this manuscript preserves the style common in Spain before the expulsion of the Jews.

This page is a fragment from a codex that included at least the whole Pentateuch. Ornate manuscripts of this type were used for studying and teaching, and served as exemplars for accurate copies of the biblical text.

“Oriental script” is one of the scripts belonging to the Islamic branch of Hebrew script. The script was prevalent in the medieval period in Egypt, the Land of Israel, Syria and Lebanon, and also in Iraq, Iran and Uzbekistan in central Asia. The use of a reed pen gives homogenous line widths, with no great difference between vertical and horizontal strokes. The roofs of the letters are characterized by serifs and prominent crowns. The height and width of square script letters are the same and the vertical lines are perpendicular to the base.

The lower half of a parchment page, apparently removed from a book binding. Worn out manuscripts were often reused to strengthen bindings.

“Oriental script” is one of the scripts belonging to the Islamic branch of Hebrew script. The script was prevalent in the medieval period in Egypt, the Land of Israel, Syria and Lebanon, and also in Iraq, Iran and Uzbekistan in central Asia. The use of a reed pen gives homogenous line widths, with no great difference between vertical and horizontal strokes. The roofs of the letters are characterized by serifs and prominent crowns. The height and width of square script letters are the same and the vertical lines are perpendicular to the base.

This work in Judeo-Arabic deals chiefly with prayer, its text and the annual cycle of festivals.

“Oriental script” is one of the scripts belonging to the Islamic branch of Hebrew script. The script was prevalent in the medieval period in Egypt, the Land of Israel, Syria and Lebanon, and also in Iraq, Iran and Uzbekistan in central Asia. The use of a reed pen gives homogenous line widths, with no great difference between vertical and horizontal strokes. The roofs of the letters are characterized by serifs and prominent crowns. The height and width of square script letters are the same and the vertical lines are perpendicular to the base.

Yemenite Jews were great admirers of Maimonides and still depend on his works for halakhic rulings. Their copies of his Mishneh Torah preserve a unique text, which Yemenites claim represents Maimonides’ final opinion.

“Yemenite script,” still used by traditional Yemenite Jews, is a variety of “Oriental script,” differing from it chiefly in broader strokes, fewer serifs on the roofs of the letters and a greater distinction between horizontal and vertical strokes.

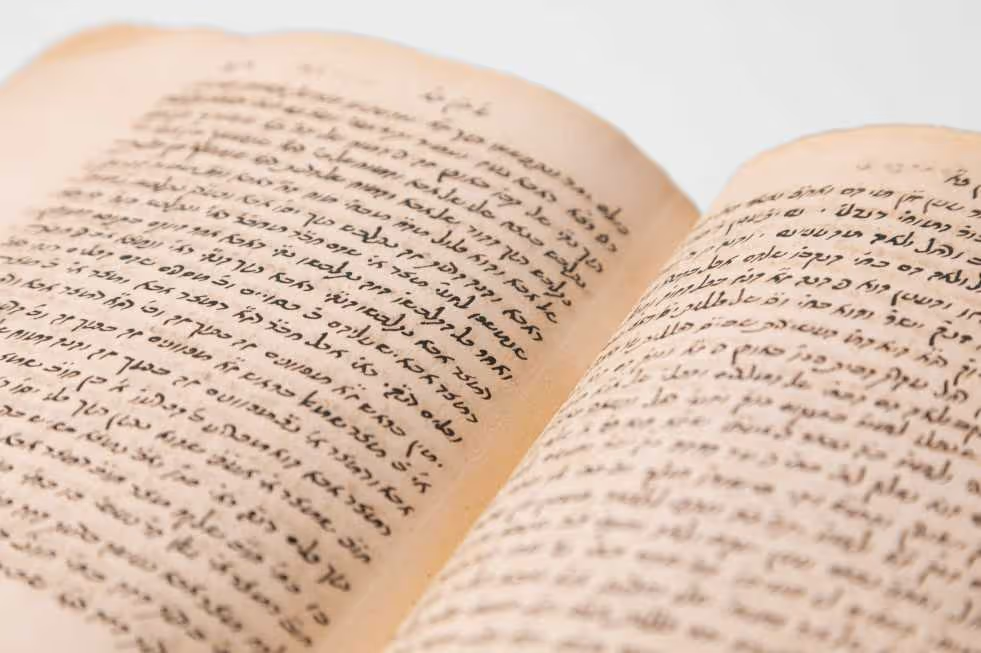

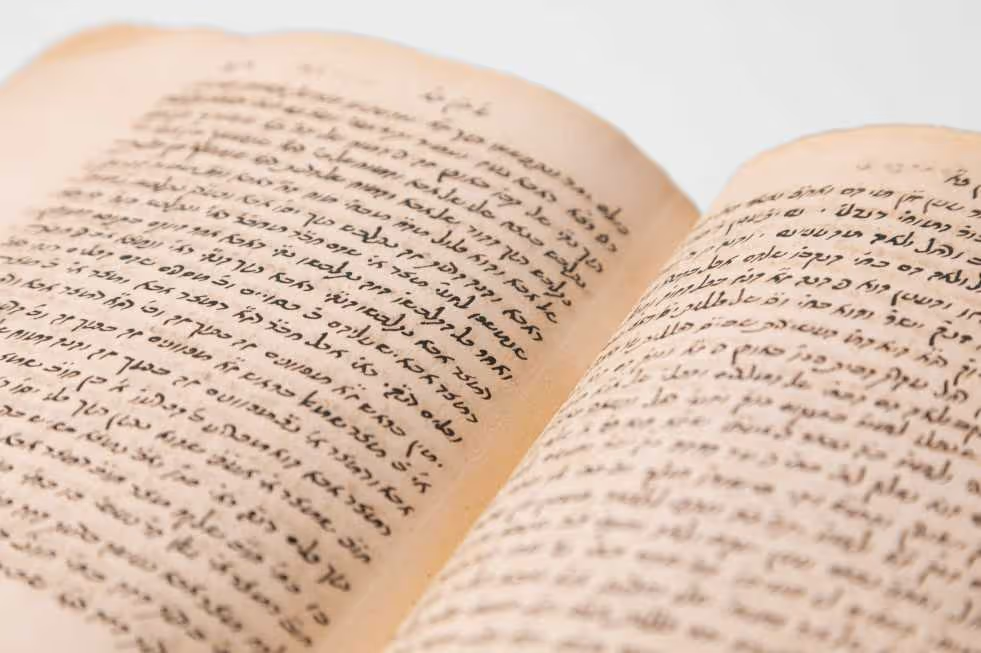

The kabbalist Rabbi Haim Vital (Safed 1542 – Damascus 1620) was the leading pupil of Rabbi Yitzhak Luria (“the Ari”) for two years, and his works are the main source for Luria’s teachings. The rapid dissemination of his writings on the Ari’s mystical doctrine completely transformed the world of Jewish mysticism. The style of writing in this manuscript preserves the style common in Spain before the expulsion of the Jews. Semi-cursive script is not as rigid as square script or a fully cursive script, and keeps each letter distinct in shape.

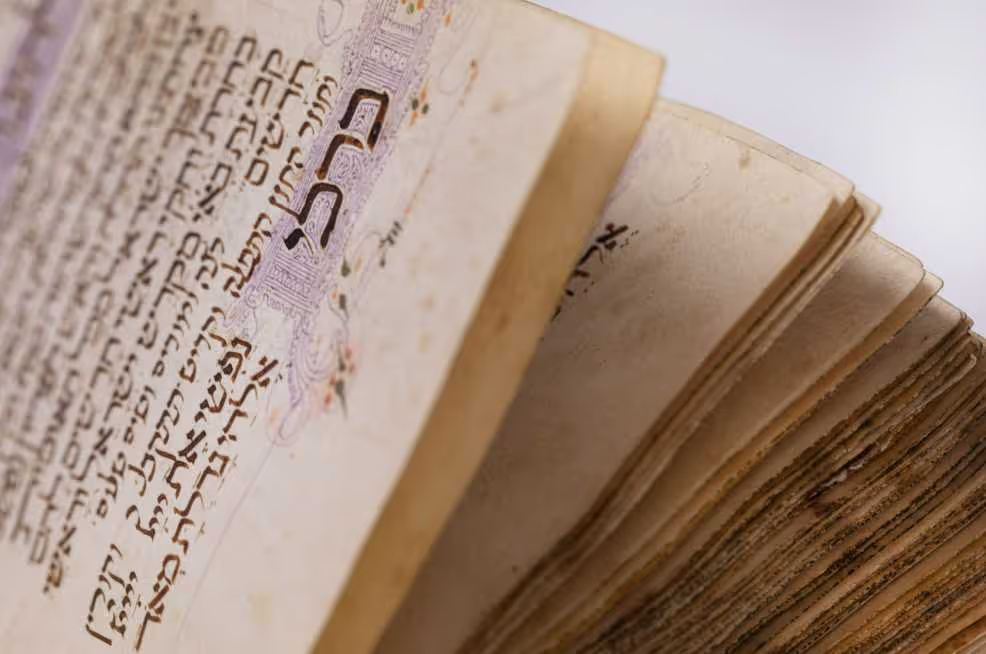

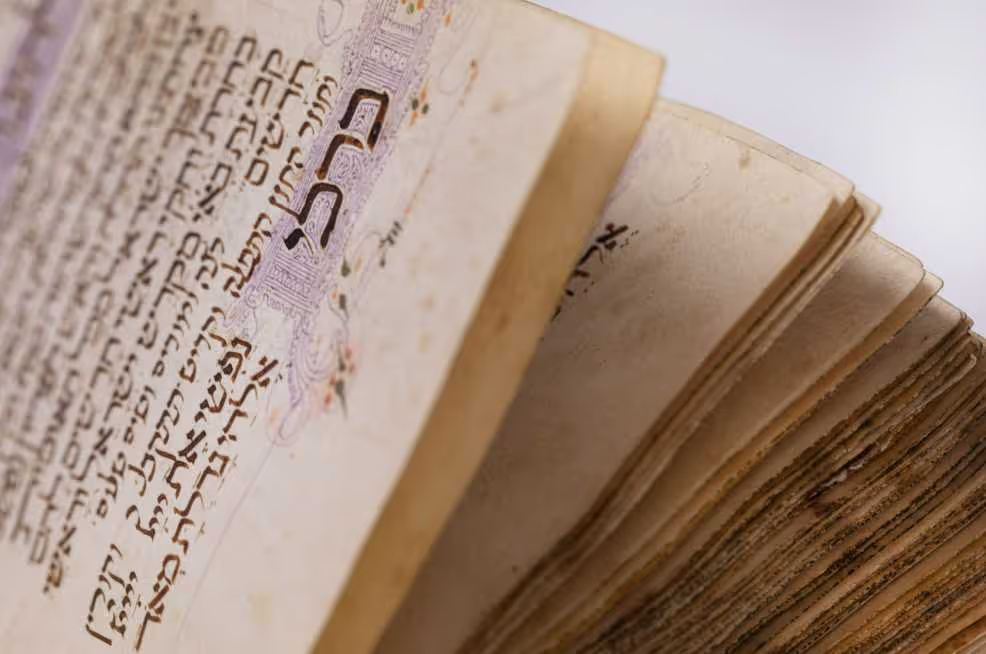

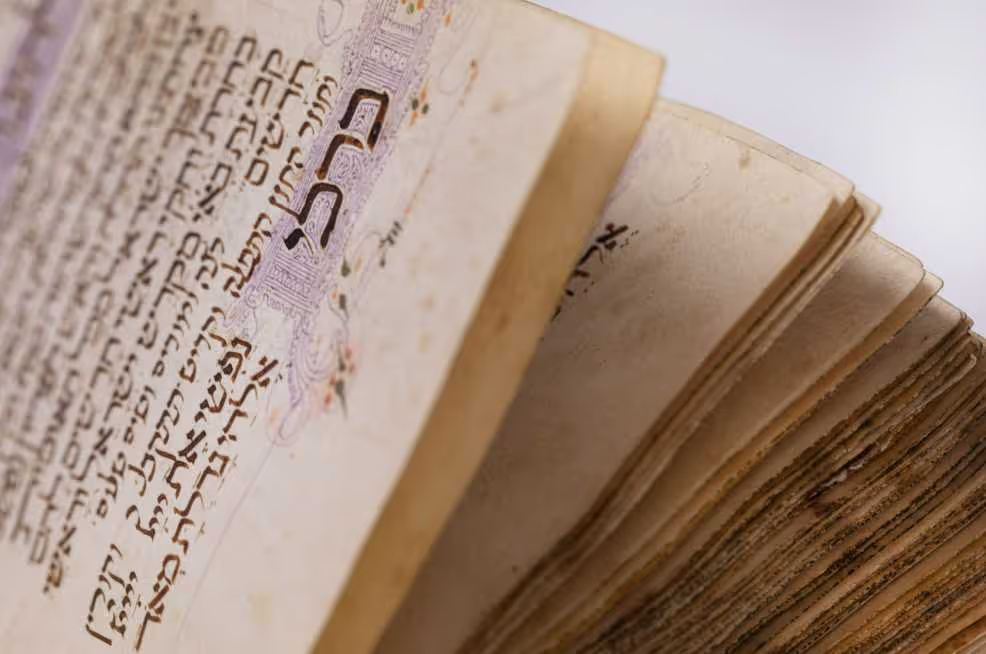

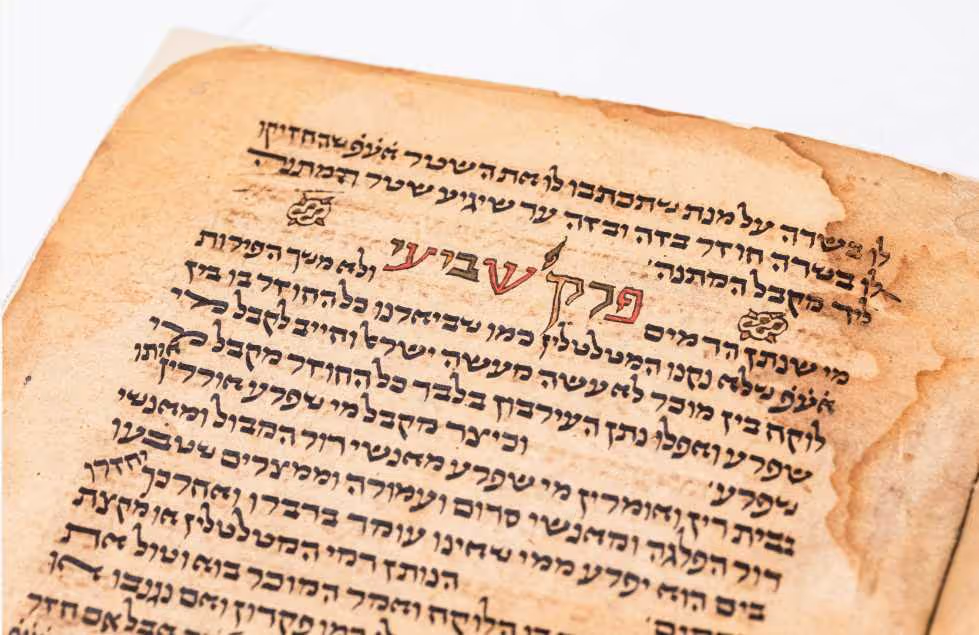

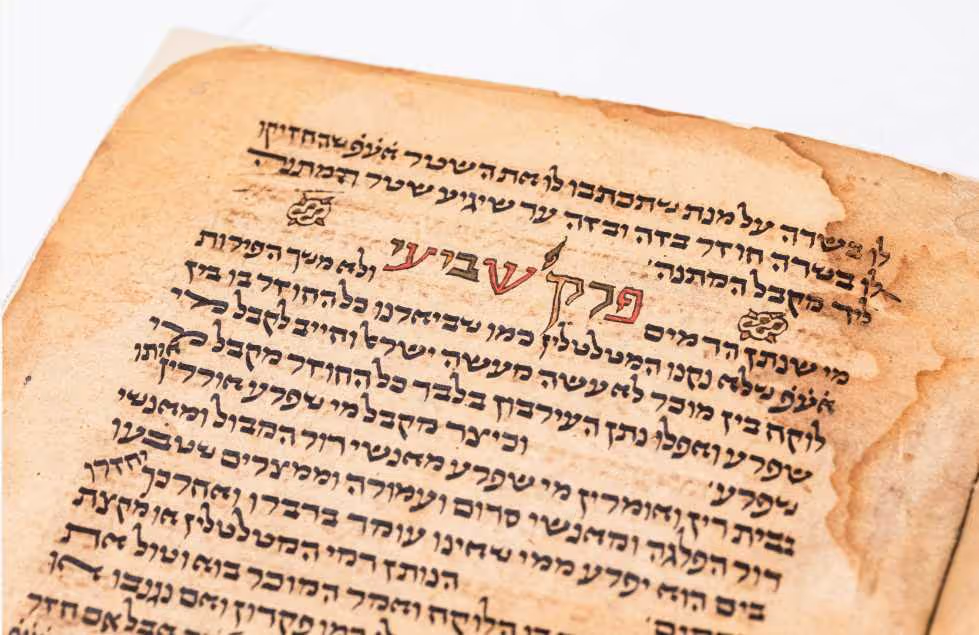

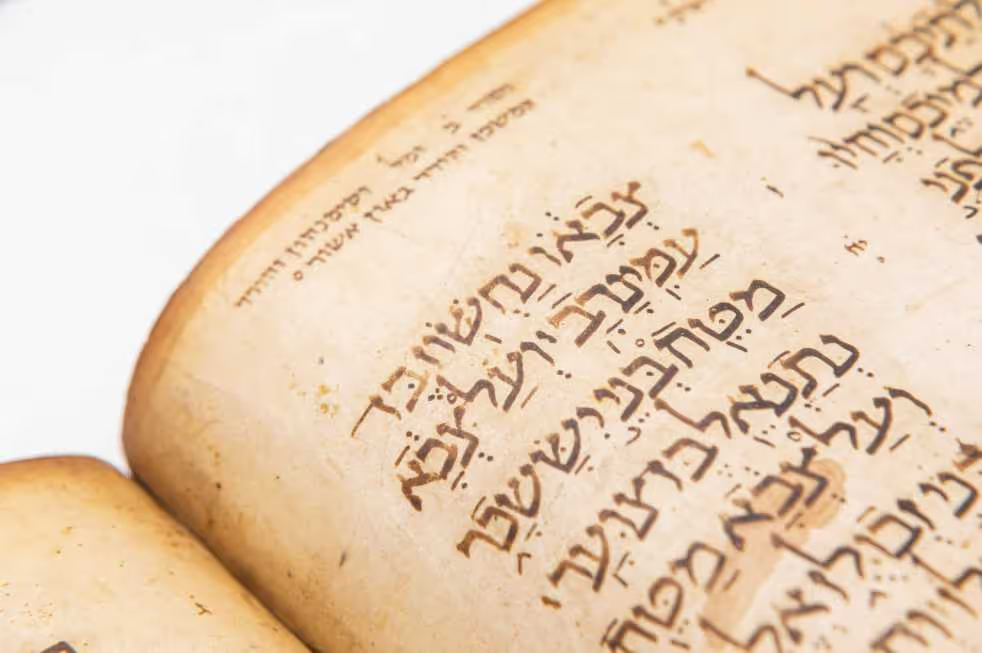

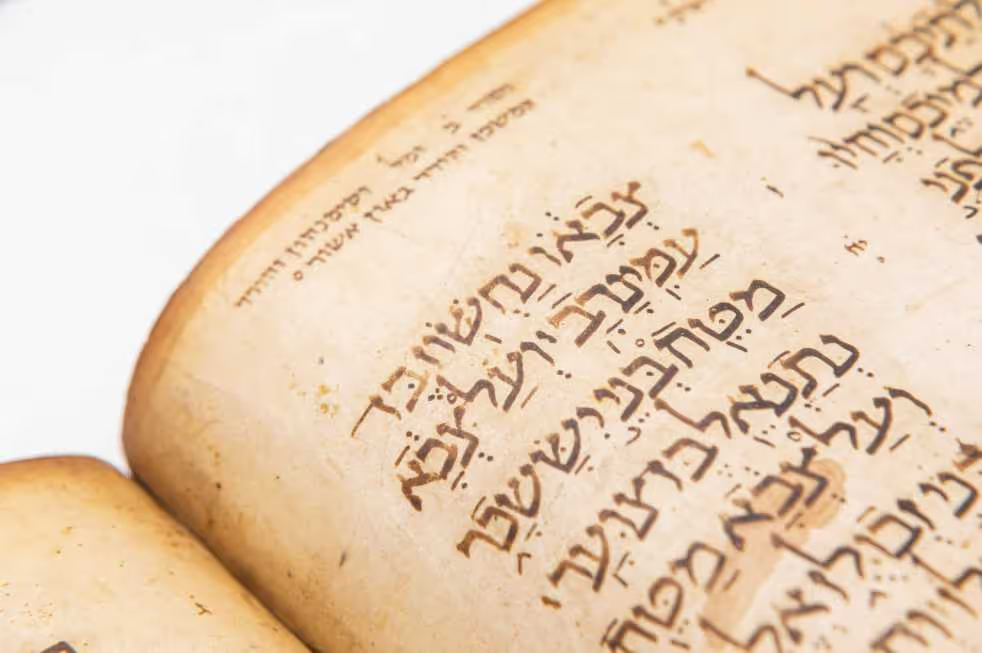

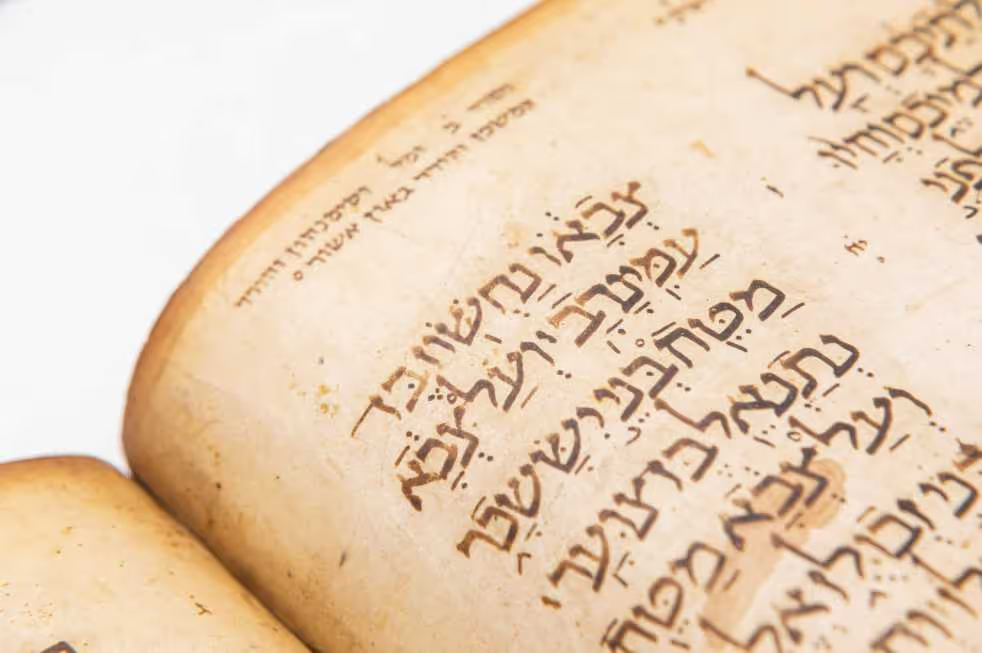

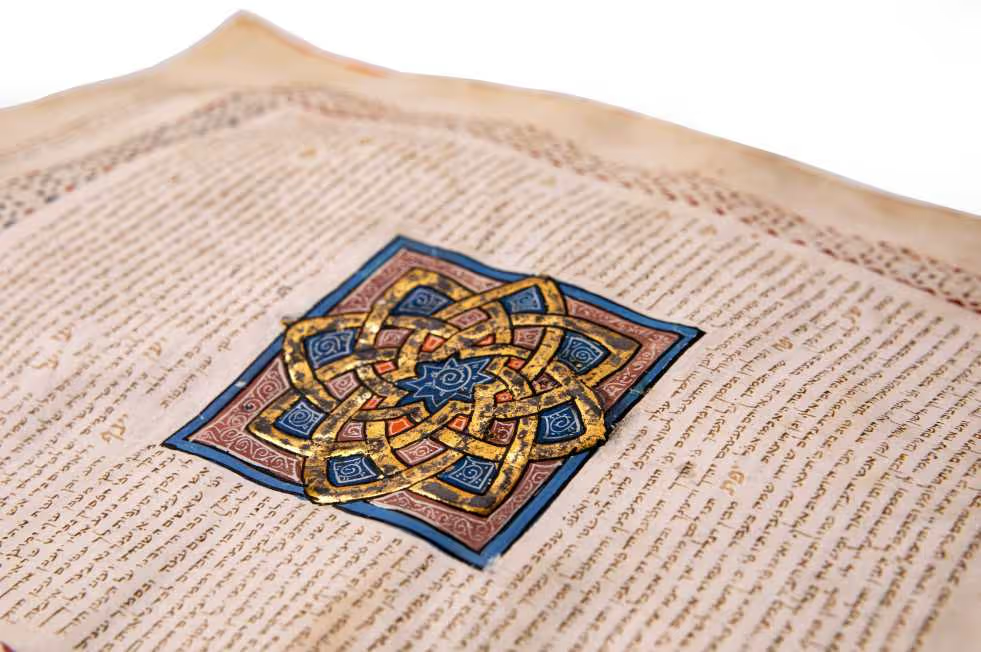

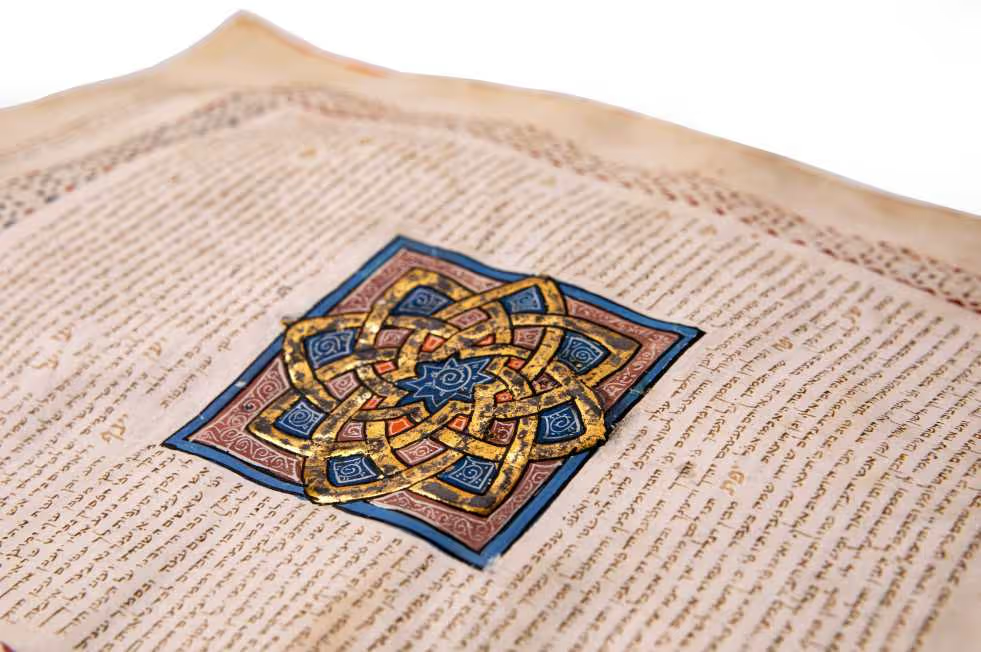

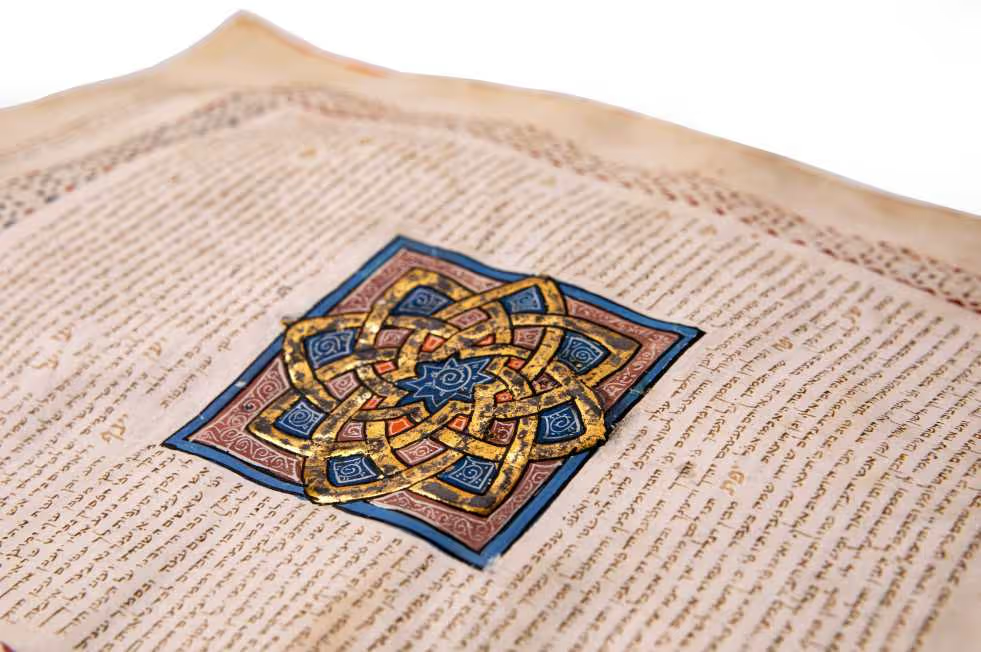

The codex displayed here is one of a small group of rare manuscripts preserved in the Library known as the “Damascus Keters.” Keter (Crown) is a term in common use in the Middle East for an ornate ancient manuscript of the Hebrew Bible or the Pentateuch. The Keters were written in various locations, transferred from one community to another and eventually reached Damascus where the Jewish community adopted them as a symbolic amulet to maintain their power, identity and unity. To this day they are considered precious treasures ranking among the most important and impressive in the Jewish world. The ancient Keter shown here contains a precise record of instructions for copying the biblical text making it an authoritative model for generations of scribes.

The codex displayed here is one of a small group of rare manuscripts preserved in the Library, known as the “Damascus Keters.” Keter (Crown) is a term in common use in the Middle East for an ornate ancient manuscript of the Hebrew Bible or the Pentateuch. The Keters were written in various locations, transferred from one community to another and eventually reached Damascus where the Jewish community adopted them as a symbolic amulet to maintain their power, identity and unity. To this day they are considered precious treasures ranking among the most important and impressive in the Jewish world.

The codex displayed here is one of a small group of rare manuscripts preserved in the Library known as the “Damascus Keters.” Keter (Crown) is a term in common use in the Middle East for an ornate ancient manuscript of the Hebrew Bible or the Pentateuch. The Keters were written in various locations, transferred from one community to another and eventually reached Damascus where the Jewish community adopted them as a symbolic amulet to maintain their power, identity and unity. To this day they are considered precious treasures ranking among the most important and impressive in the Jewish world.

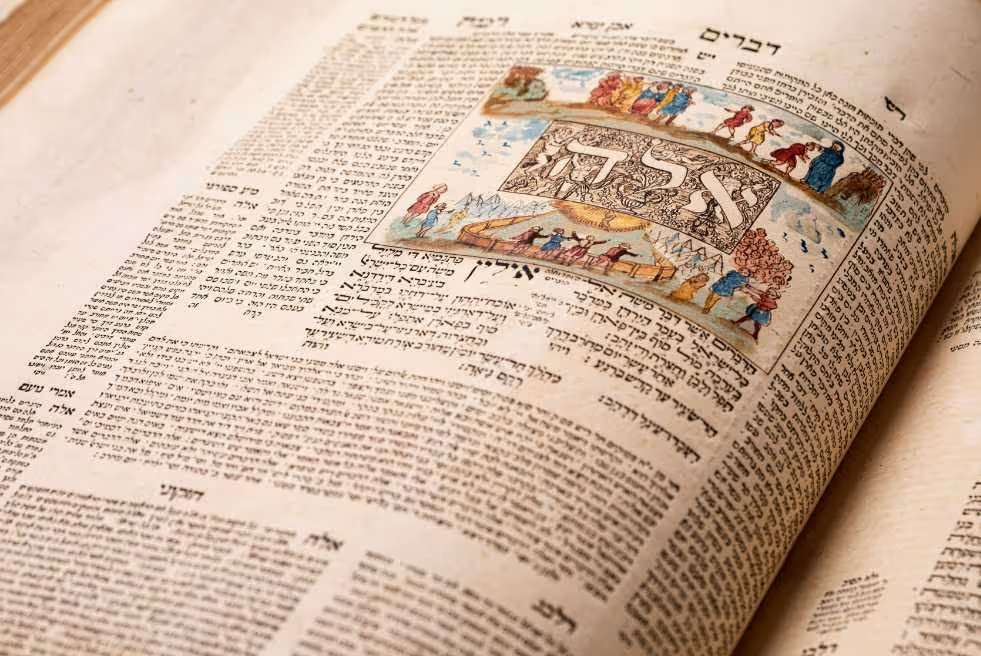

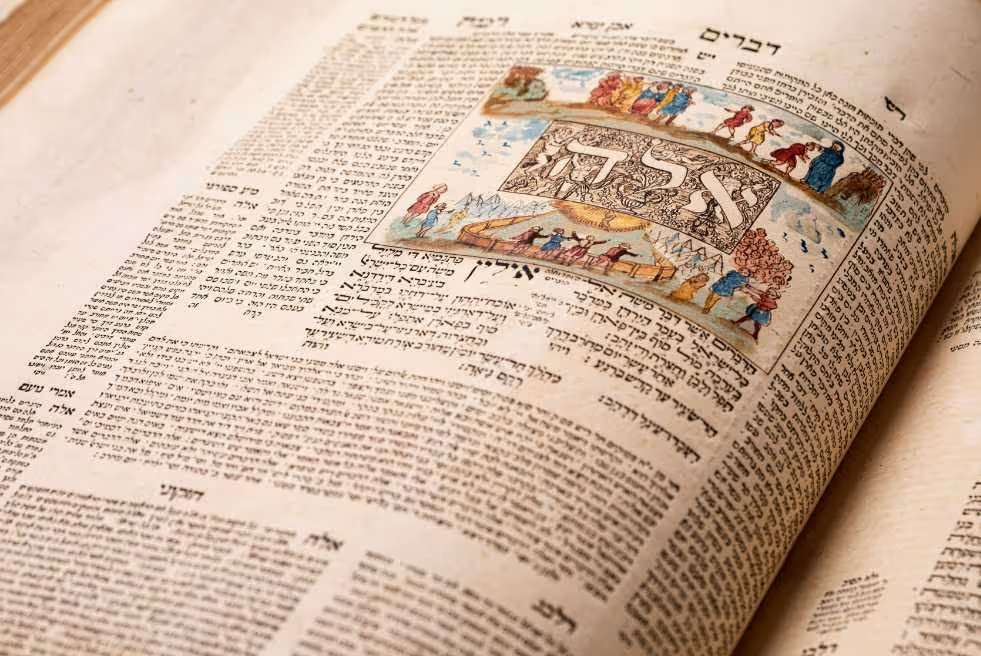

Mikraʾot Gedolot is the term for printed editions of the Hebrew Bible containing the canonical and sanctified text together with the traditional Aramaic translations and a selection of commentaries, with a graphic design enabling the reader to follow each one separately. This edition of Mikraʾot Gedolot is distinguished by its large format, high-quality paper and most of all by the magnificent illustrations added to the printed pages by an artist. In the early 18th century, Amsterdam was a world center for Judaica printing.

.avif)

.svg)