The song Hava Nagila is one of the most popular Jewish and universal songs still sung and performed today by professionals and amateurs around the world. This song, often performed by wedding bands, street buskers and jazz musicians, actually originated as a Hasidic religious melody. The melody was adapted by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, who transformed it into a song carrying an overtly political message. Hava Nagila was composed by Idelsohn in 1918 as a celebration of the Balfour Declaration and General Edmund Allenby's capture of Jerusalem, both of which had happened shortly beforehand. Idelsohn intended it to be a joyous song, performed by a choir.

At the time, Idelsohn lived in Jerusalem, where he conducted a men's choir and worked as a well-known composer, researcher and teacher of music. Musicologist Eliyahu HaCohen explains that when locals were caught up in the excitement of the moment and began to celebrate the British conquest of Jerusalem, all eyes were on Idelsohn, in the hopes that he’d be able to come up with the ultimate song to express the magnitude of what had happened and what the public was feeling. Idelsohn was able to deliver. It is interesting to note, that although he could have composed an entirely new song, Idelsohn decided to make use of a Hasidic melody for this significant occasion.

.avif)

The song Hava Nagila is one of the most popular Jewish and universal songs still sung and performed today by professionals and amateurs around the world. This song, often performed by wedding bands, street buskers and jazz musicians, actually originated as a Hasidic religious melody. The melody was adapted by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, who transformed it into a song carrying an overtly political message. Hava Nagila was composed by Idelsohn in 1918 as a celebration of the Balfour Declaration and General Edmund Allenby's capture of Jerusalem, both of which had happened shortly beforehand. Idelsohn intended it to be a joyous song, performed by a choir.

At the time, Idelsohn lived in Jerusalem, where he conducted a men's choir and worked as a well-known composer, researcher and teacher of music. Musicologist Eliyahu HaCohen explains that when locals were caught up in the excitement of the moment and began to celebrate the British conquest of Jerusalem, all eyes were on Idelsohn, in the hopes that he’d be able to come up with the ultimate song to express the magnitude of what had happened and what the public was feeling. Idelsohn was able to deliver. It is interesting to note, that although he could have composed an entirely new song, Idelsohn decided to make use of a Hasidic melody for this significant occasion.

.avif)

The song Hava Nagila is one of the most popular Jewish and universal songs still sung and performed today by professionals and amateurs around the world. This song, often performed by wedding bands, street buskers and jazz musicians, actually originated as a Hasidic religious melody. The melody was adapted by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, who transformed it into a song carrying an overtly political message. Hava Nagila was composed by Idelsohn in 1918 as a celebration of the Balfour Declaration and General Edmund Allenby's capture of Jerusalem, both of which had happened shortly beforehand. Idelsohn intended it to be a joyous song, performed by a choir.

At the time, Idelsohn lived in Jerusalem, where he conducted a men's choir and worked as a well-known composer, researcher and teacher of music. Musicologist Eliyahu HaCohen explains that when locals were caught up in the excitement of the moment and began to celebrate the British conquest of Jerusalem, all eyes were on Idelsohn, in the hopes that he’d be able to come up with the ultimate song to express the magnitude of what had happened and what the public was feeling. Idelsohn was able to deliver. It is interesting to note, that although he could have composed an entirely new song, Idelsohn decided to make use of a Hasidic melody for this significant occasion.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

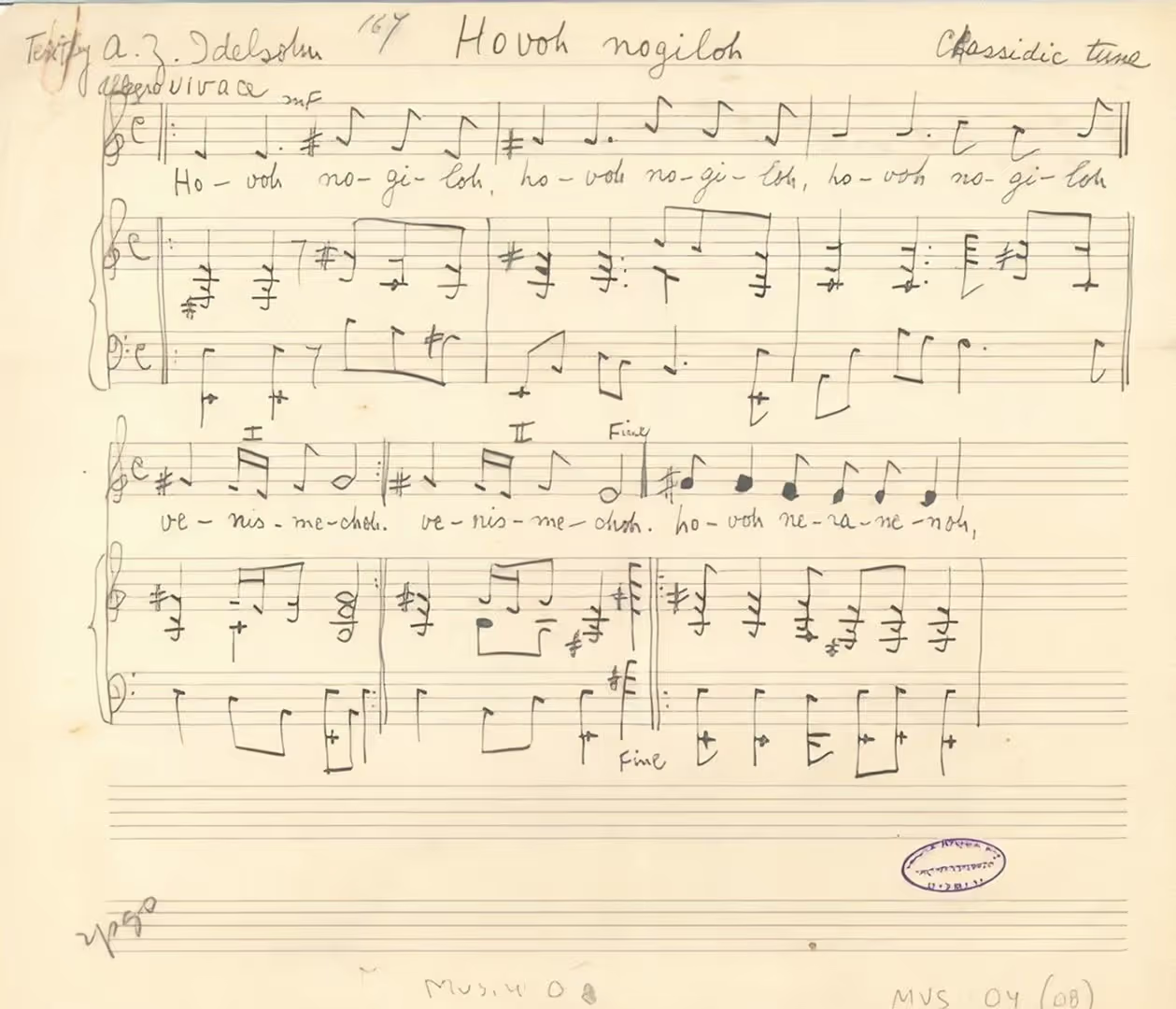

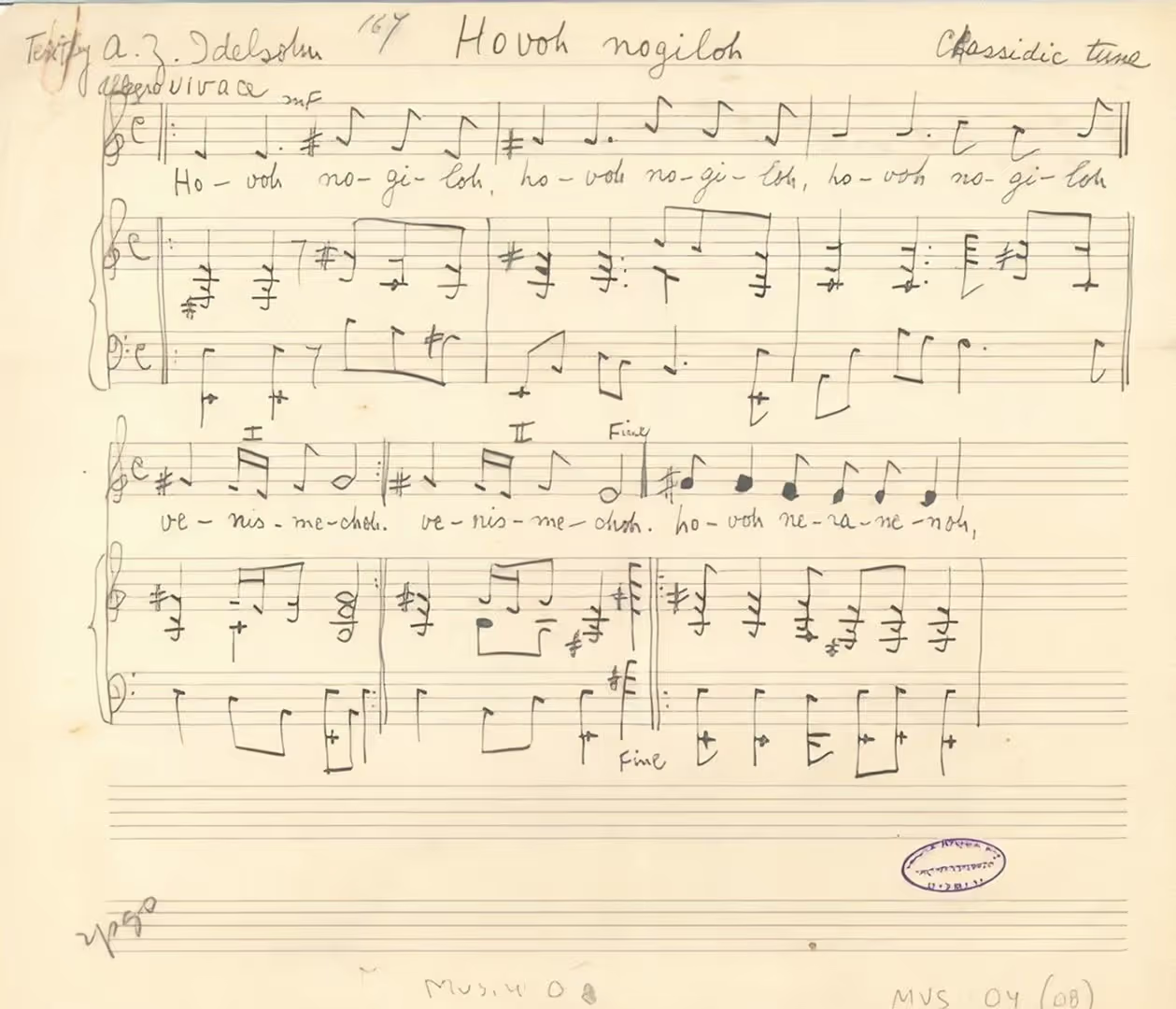

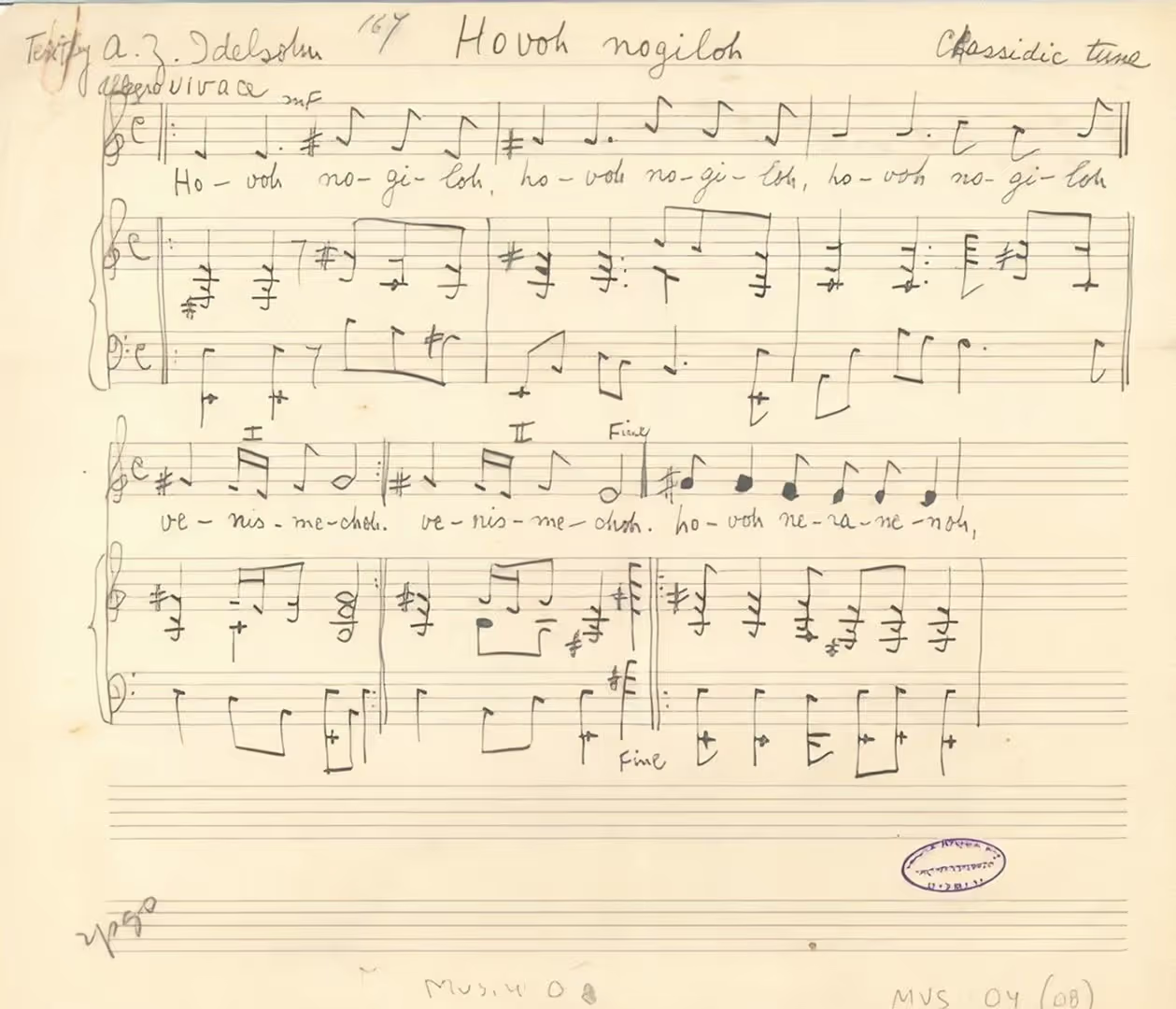

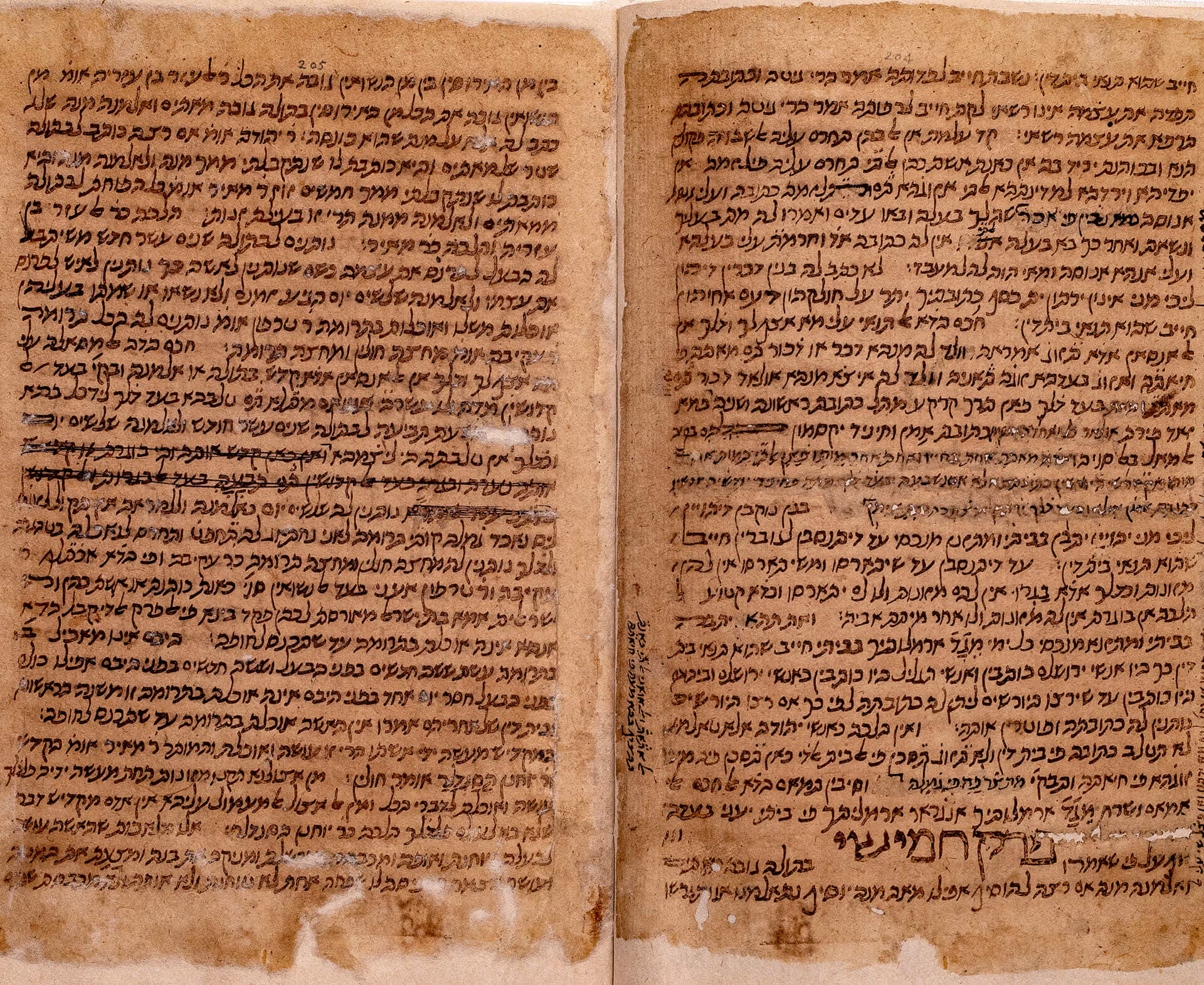

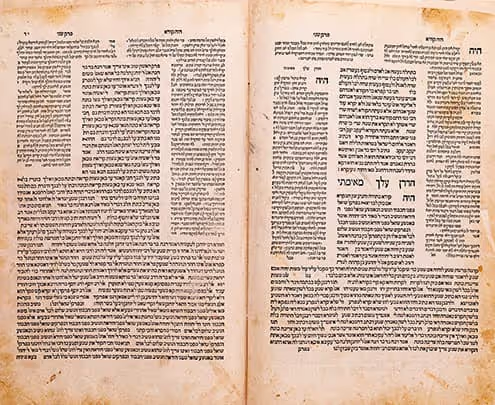

Idelsohn adapted a festive niggun (Jewish religious melody) associated with the Sadigora Hasidim, which he would later publish in his Thesaurus (vol. 10, "The Songs of the Hasidim", no. 155). He also changed the order of the musical motifs and added lyrics. The song itself also appeared in his Thesaurus, in volume 9, among the "Songs of Eastern European Jews" (song no. 716).

Idelsohn wrote that he originally transcribed the melody from a Sadigurer Hasid in Jerusalem in 1915. The Sadigura Hasidic community traced their roots to the town of Sadigura in the Bukovina region of Habsburg Austria (present day Ukraine). The Sadigurer Hasidim remained in central Europe until the First World War when their leaders fled to Vienna and eventually to Tel Aviv in 1938. A small subgroup of these Hasidim had already arrived in Jerusalem at a much earlier stage. Idelsohn could have heard the tune in Jerusalem, or even in Vienna during his stay there between 1913 and 1914.

The melody is built on short motifs, and has three sections- which originally were in a different order. It is in an ahava raba mode, a Jewish Ashkenazi mode which is used in all genres of Ashkenazic music. The rhythm is 4/4 and the instructions occasionally note - "in a marching tempo".

"Hava nagila ve nismeha, hava neranena, 'uru ahim belev sameah" -"Come, let us rejoice, let us rejoice and be happy." These lines closely echo the biblical verse from Psalm 118:24 - "This is the day that the Lord has made; Let us exult and rejoice in it" - which is recited during the Hallel, the special set of Psalms of thanksgiving added to the Jewish liturgy of festivals and other joyous occasions. For Idelsohn, as a Zionist activist, this occasion represented the tangible beginnings of the fulfillment of the dream of a Jewish national homeland.

The song expresses a happiness which originated in Hasidic mystical roots in Eastern Europe, and which was given new meaning with the historical events in Ottoman/British Palestine, thus becoming a universal symbol of Jewish joy.

Idelsohn adapted a festive niggun (Jewish religious melody) associated with the Sadigora Hasidim, which he would later publish in his Thesaurus (vol. 10, "The Songs of the Hasidim", no. 155). He also changed the order of the musical motifs and added lyrics. The song itself also appeared in his Thesaurus, in volume 9, among the "Songs of Eastern European Jews" (song no. 716).

Idelsohn wrote that he originally transcribed the melody from a Sadigurer Hasid in Jerusalem in 1915. The Sadigura Hasidic community traced their roots to the town of Sadigura in the Bukovina region of Habsburg Austria (present day Ukraine). The Sadigurer Hasidim remained in central Europe until the First World War when their leaders fled to Vienna and eventually to Tel Aviv in 1938. A small subgroup of these Hasidim had already arrived in Jerusalem at a much earlier stage. Idelsohn could have heard the tune in Jerusalem, or even in Vienna during his stay there between 1913 and 1914.

The melody is built on short motifs, and has three sections- which originally were in a different order. It is in an ahava raba mode, a Jewish Ashkenazi mode which is used in all genres of Ashkenazic music. The rhythm is 4/4 and the instructions occasionally note - "in a marching tempo".

"Hava nagila ve nismeha, hava neranena, 'uru ahim belev sameah" -"Come, let us rejoice, let us rejoice and be happy." These lines closely echo the biblical verse from Psalm 118:24 - "This is the day that the Lord has made; Let us exult and rejoice in it" - which is recited during the Hallel, the special set of Psalms of thanksgiving added to the Jewish liturgy of festivals and other joyous occasions. For Idelsohn, as a Zionist activist, this occasion represented the tangible beginnings of the fulfillment of the dream of a Jewish national homeland.

The song expresses a happiness which originated in Hasidic mystical roots in Eastern Europe, and which was given new meaning with the historical events in Ottoman/British Palestine, thus becoming a universal symbol of Jewish joy.

Idelsohn adapted a festive niggun (Jewish religious melody) associated with the Sadigora Hasidim, which he would later publish in his Thesaurus (vol. 10, "The Songs of the Hasidim", no. 155). He also changed the order of the musical motifs and added lyrics. The song itself also appeared in his Thesaurus, in volume 9, among the "Songs of Eastern European Jews" (song no. 716).

Idelsohn wrote that he originally transcribed the melody from a Sadigurer Hasid in Jerusalem in 1915. The Sadigura Hasidic community traced their roots to the town of Sadigura in the Bukovina region of Habsburg Austria (present day Ukraine). The Sadigurer Hasidim remained in central Europe until the First World War when their leaders fled to Vienna and eventually to Tel Aviv in 1938. A small subgroup of these Hasidim had already arrived in Jerusalem at a much earlier stage. Idelsohn could have heard the tune in Jerusalem, or even in Vienna during his stay there between 1913 and 1914.

The melody is built on short motifs, and has three sections- which originally were in a different order. It is in an ahava raba mode, a Jewish Ashkenazi mode which is used in all genres of Ashkenazic music. The rhythm is 4/4 and the instructions occasionally note - "in a marching tempo".

"Hava nagila ve nismeha, hava neranena, 'uru ahim belev sameah" -"Come, let us rejoice, let us rejoice and be happy." These lines closely echo the biblical verse from Psalm 118:24 - "This is the day that the Lord has made; Let us exult and rejoice in it" - which is recited during the Hallel, the special set of Psalms of thanksgiving added to the Jewish liturgy of festivals and other joyous occasions. For Idelsohn, as a Zionist activist, this occasion represented the tangible beginnings of the fulfillment of the dream of a Jewish national homeland.

The song expresses a happiness which originated in Hasidic mystical roots in Eastern Europe, and which was given new meaning with the historical events in Ottoman/British Palestine, thus becoming a universal symbol of Jewish joy.

Idelsohn recorded the song with a small men's choir on a commercial record in Berlin in 1922, on the German label Polydor (record no. TAK-0331 in the Music Dept. at the NLI)

Idelsohn recorded the song with a small men's choir on a commercial record in Berlin in 1922, on the German label Polydor (record no. TAK-0331 in the Music Dept. at the NLI)

Idelsohn recorded the song with a small men's choir on a commercial record in Berlin in 1922, on the German label Polydor (record no. TAK-0331 in the Music Dept. at the NLI)

Writing and research: Dr. Gila Flam and Dr. Tamar Zigman, NLI Music Department

Writing and research: Dr. Gila Flam and Dr. Tamar Zigman, NLI Music Department

Writing and research: Dr. Gila Flam and Dr. Tamar Zigman, NLI Music Department

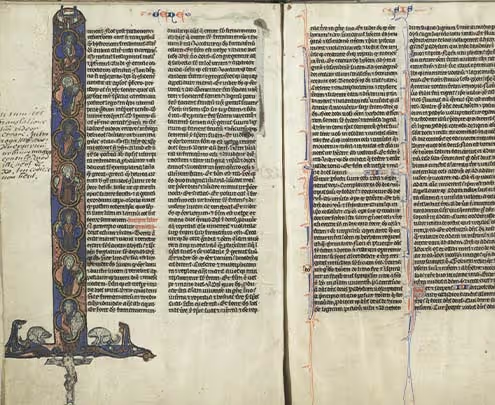

tab1img1=Jerusalem changes hands: the ceremony led by General Allenby on December 11, 1917, at the entrance to the Tower of David

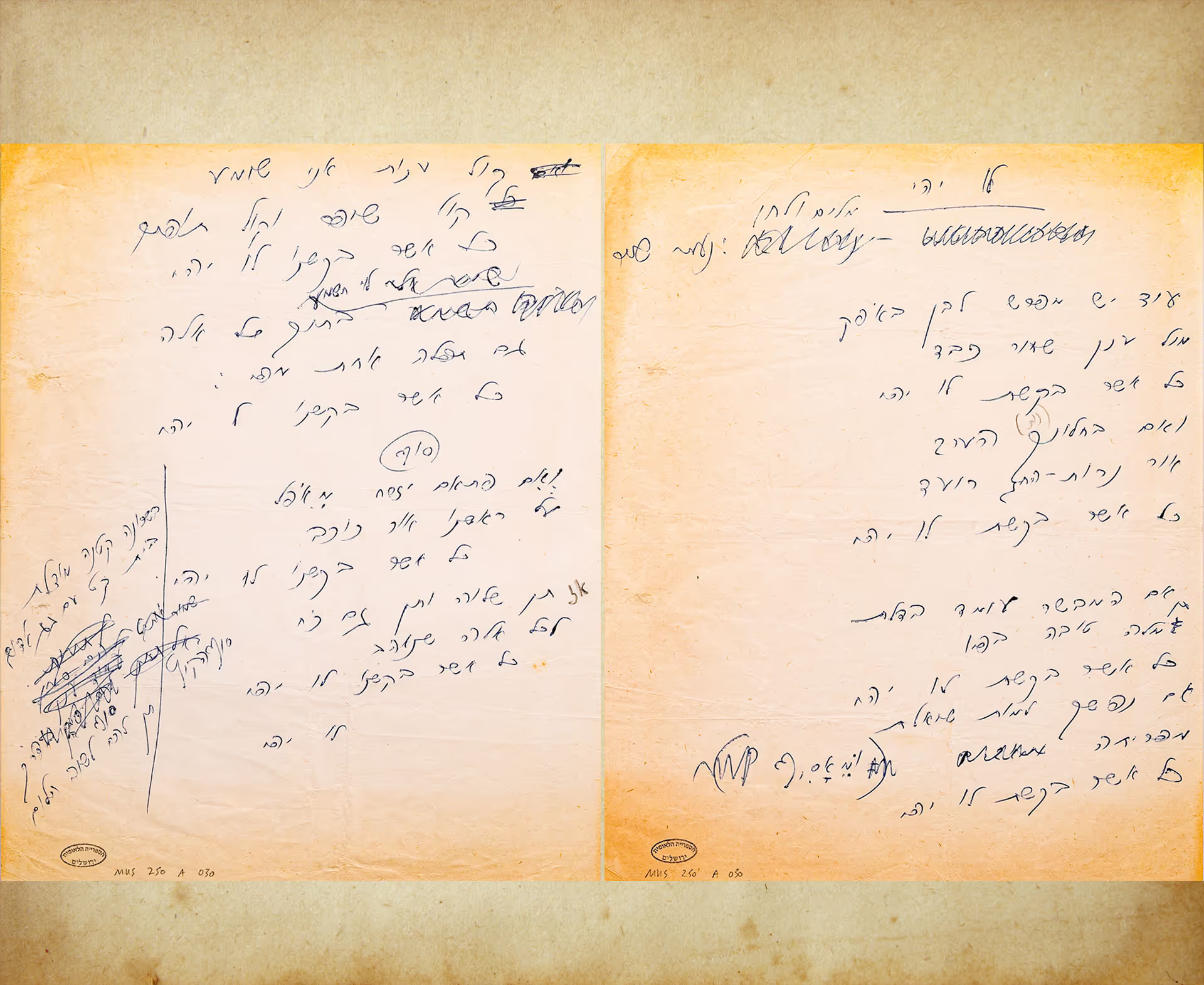

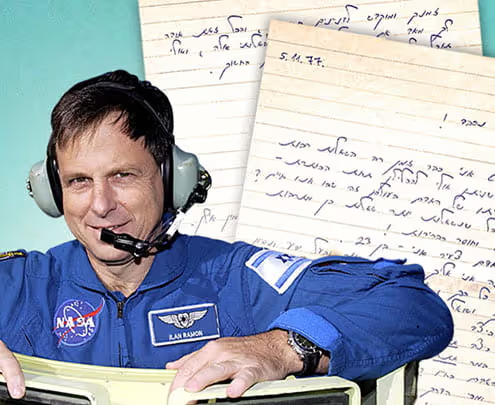

tab2img3=The original score of Hava Nagila, in Idelsohn’s handwriting

tab4img2=Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, the Abraham Schwadron Portrait Collection, the National Library of Israel

.avif)

.svg)