Baron Edmond de Rothschild was a well-known collector. “The Famous Benefactor”, as the Baron was known in the Land of Israel, began collecting books while he was still in his twenties. Edmond added dozens of manuscripts to the forty or so he had inherited from his father. The majority of these were Christian texts or historical novels, but as an observant Jew he also collected Jewish manuscripts. He owned fourteen of these handwritten works, including two bibles, several Passover Haggadot and a festival prayer book from 1492.

The Baron died in Paris in 1934, and his manuscripts were divided between his three children: James, Maurice and Miriam (Alexandrine). For reasons which remain a mystery to this day, James Rothschild – who immigrated to England in his youth - decided to leave six of the Hebrew manuscripts he inherited in France. Among these were several Passover Haggadot.

Baron Edmond de Rothschild was a well-known collector. “The Famous Benefactor”, as the Baron was known in the Land of Israel, began collecting books while he was still in his twenties. Edmond added dozens of manuscripts to the forty or so he had inherited from his father. The majority of these were Christian texts or historical novels, but as an observant Jew he also collected Jewish manuscripts. He owned fourteen of these handwritten works, including two bibles, several Passover Haggadot and a festival prayer book from 1492.

The Baron died in Paris in 1934, and his manuscripts were divided between his three children: James, Maurice and Miriam (Alexandrine). For reasons which remain a mystery to this day, James Rothschild – who immigrated to England in his youth - decided to leave six of the Hebrew manuscripts he inherited in France. Among these were several Passover Haggadot.

Baron Edmond de Rothschild was a well-known collector. “The Famous Benefactor”, as the Baron was known in the Land of Israel, began collecting books while he was still in his twenties. Edmond added dozens of manuscripts to the forty or so he had inherited from his father. The majority of these were Christian texts or historical novels, but as an observant Jew he also collected Jewish manuscripts. He owned fourteen of these handwritten works, including two bibles, several Passover Haggadot and a festival prayer book from 1492.

The Baron died in Paris in 1934, and his manuscripts were divided between his three children: James, Maurice and Miriam (Alexandrine). For reasons which remain a mystery to this day, James Rothschild – who immigrated to England in his youth - decided to leave six of the Hebrew manuscripts he inherited in France. Among these were several Passover Haggadot.

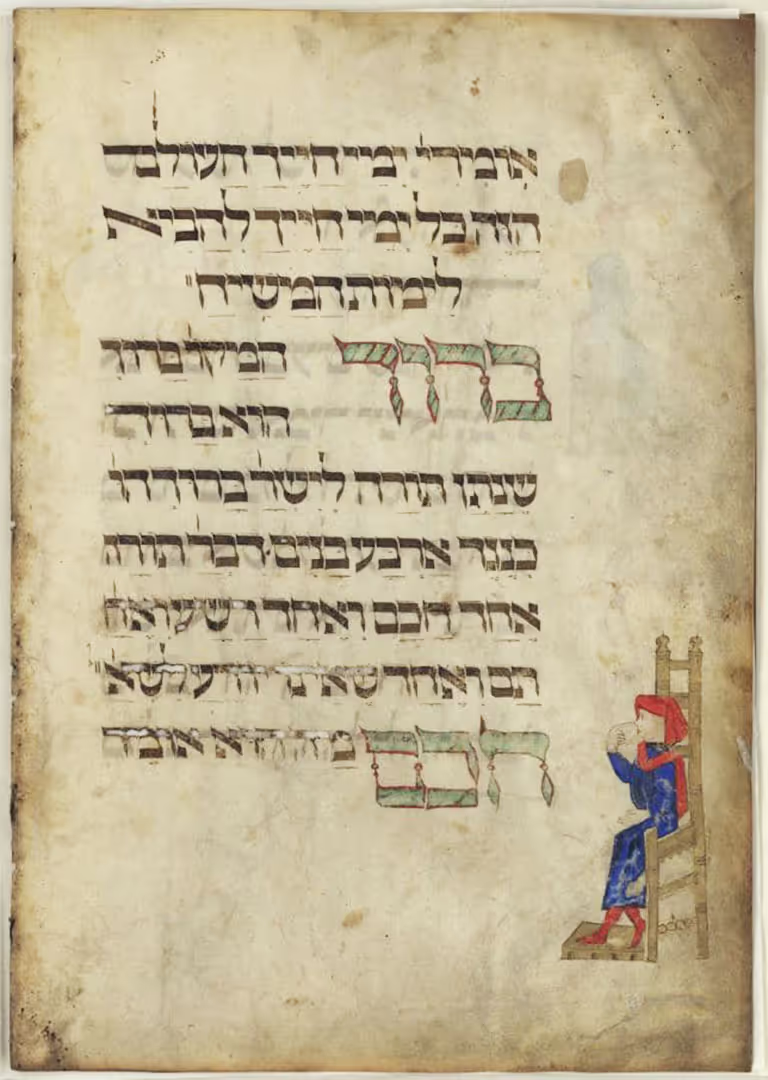

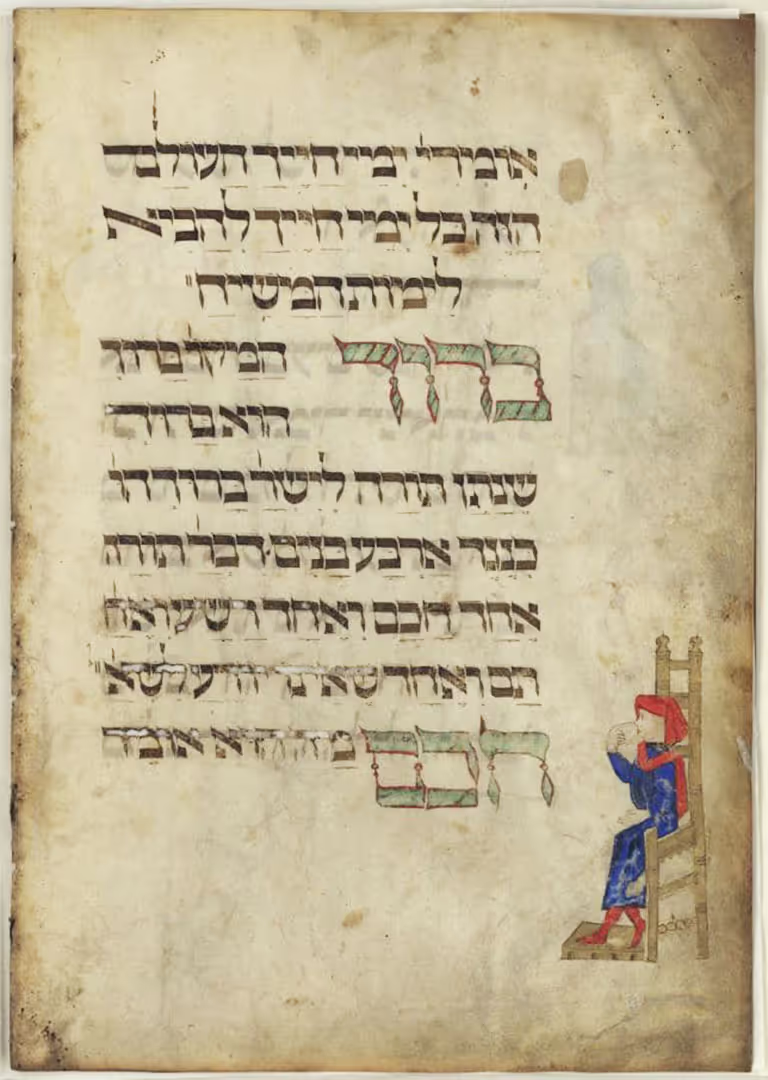

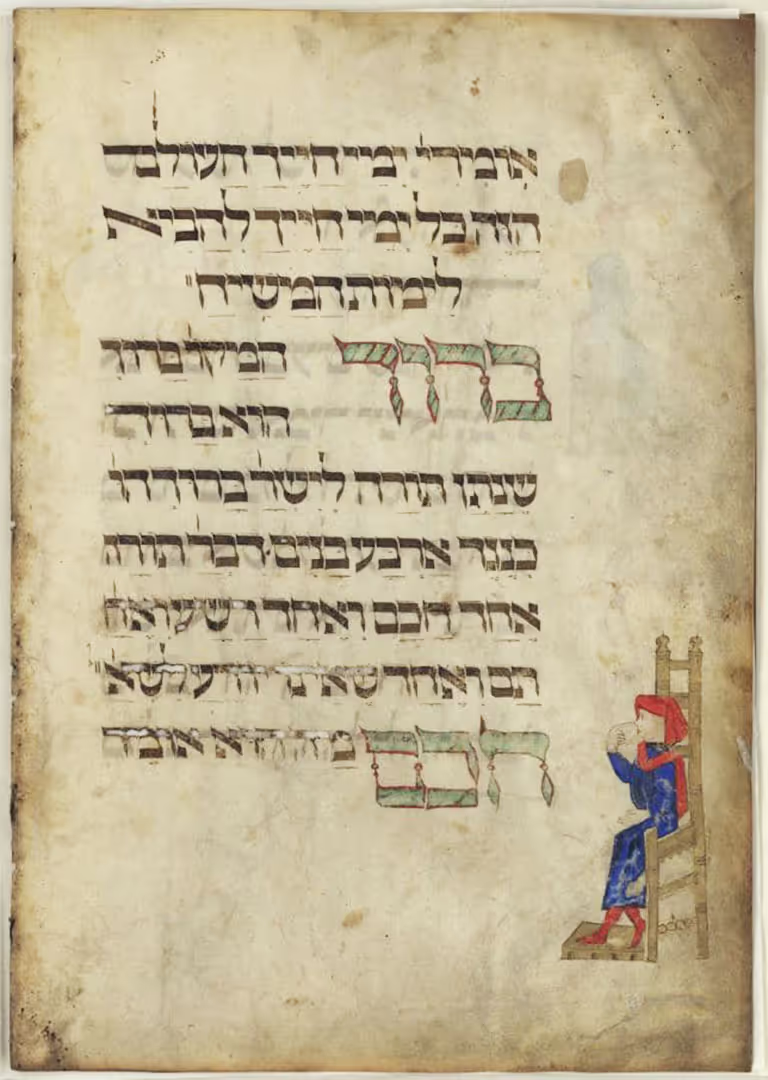

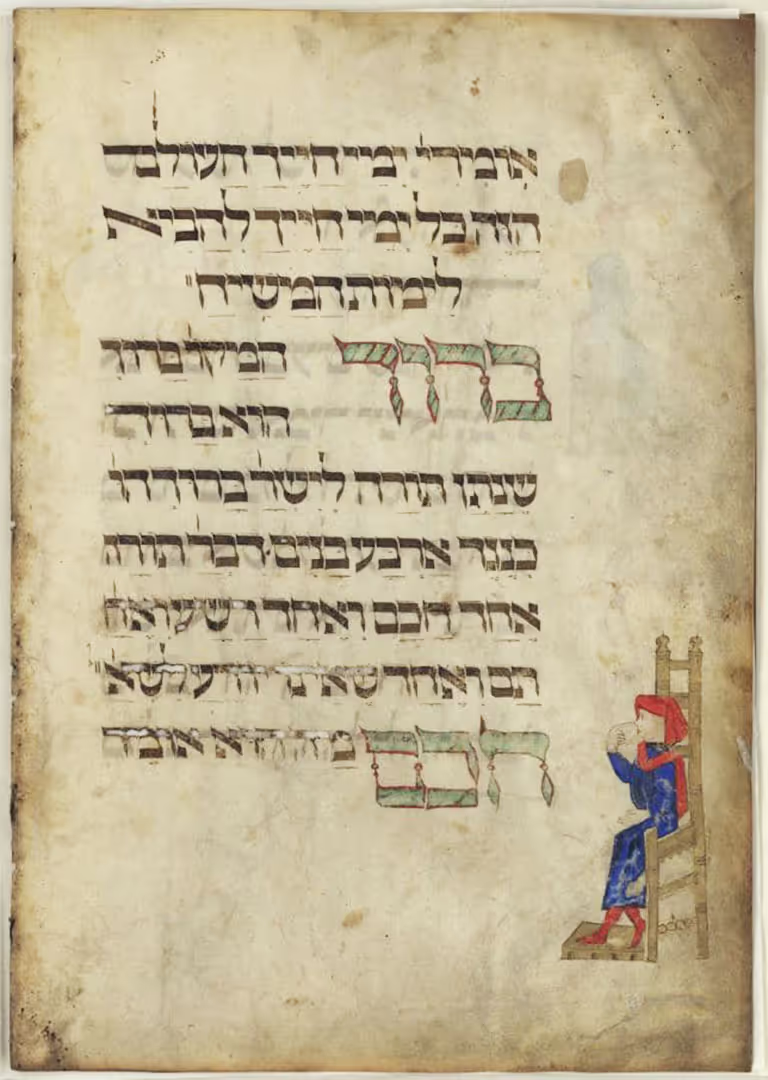

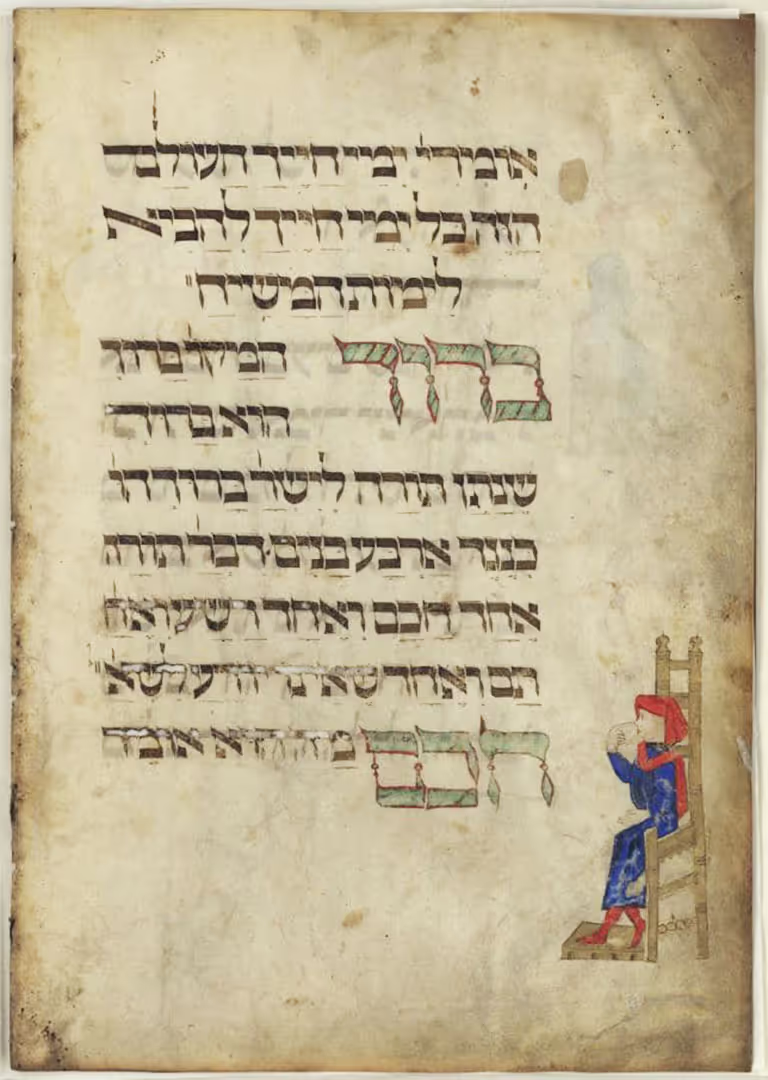

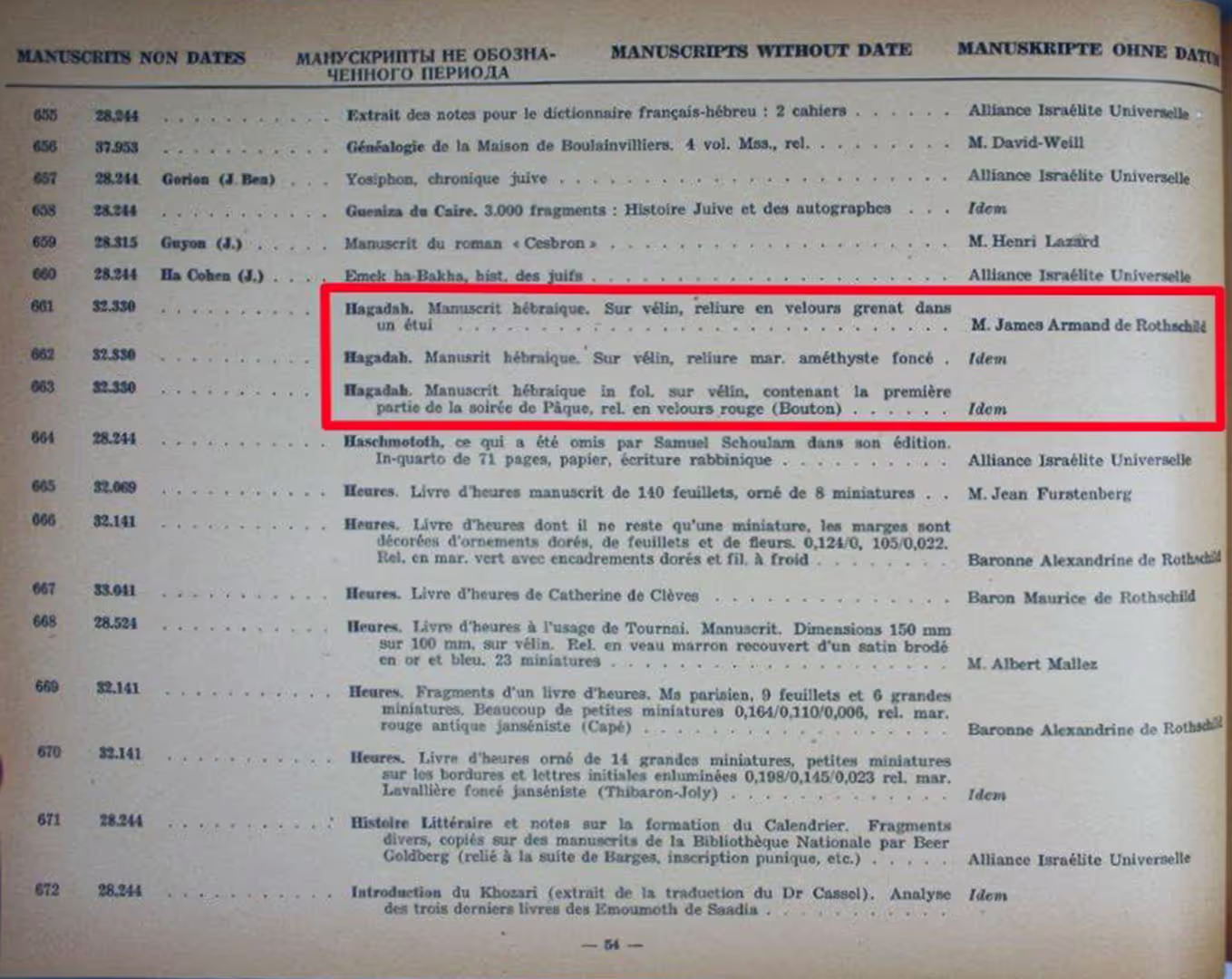

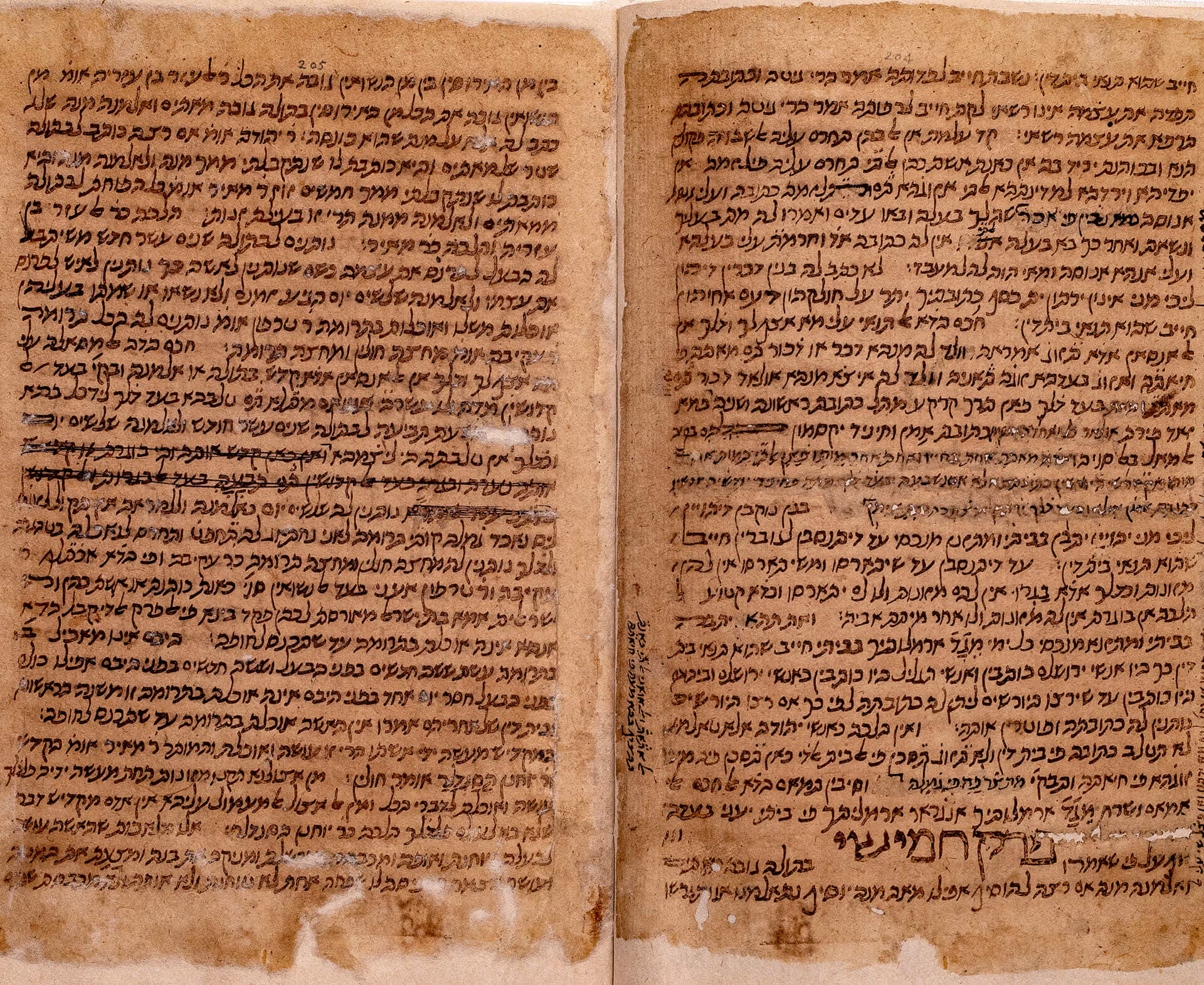

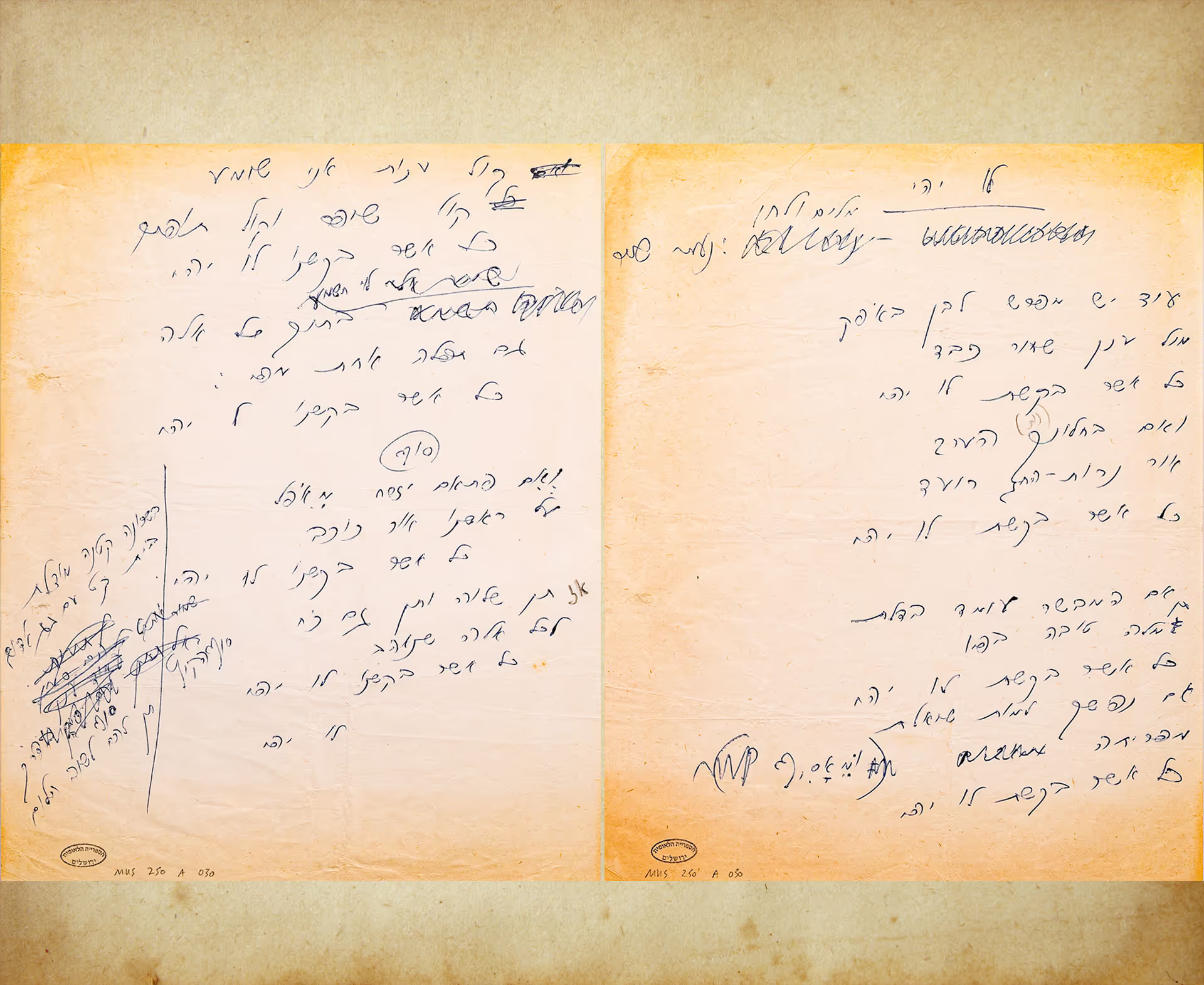

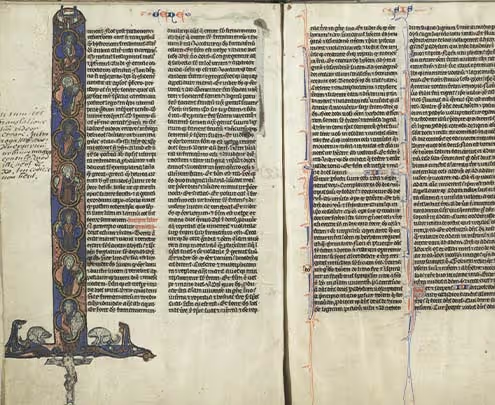

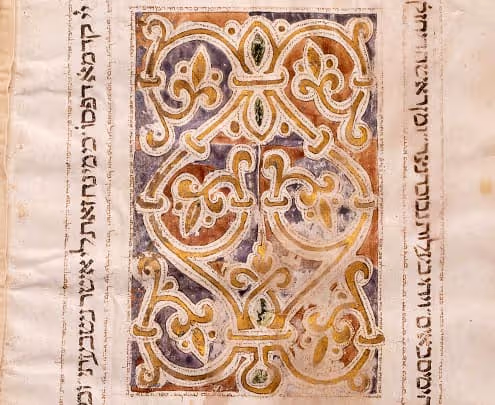

One of these Haggadot contains some fifty pages written in quadratic Ashkenazi script, accompanied by dozens of colorful illustrations. Some of the wonderful illustrations in this Haggadah are connected to the text itself, and some contain motifs connected to the Haggadah and the story of the Exodus from Egypt – the ten plagues, matzah baking, and more.

This Haggadah would later become known as the "Rothschild Haggadah." Some of the illustrations in the Haggadah provide details regarding its source. The cities of Pithom and Ramses feature late gothic architecture, reminiscent of Northern Italian fortresses. The figures depicted in the Haggadah are also dressed in clothing typical of Northern Italy. The illustrator's name does not appear, but the style is reminiscent of that of a famous illustrator named Yoel Ben Shimon. Information taken from other manuscripts indicates that Yoel Ben Shimon was active in the second half of the 15th century in the cities of Modena and Cremona in Northern Italy.

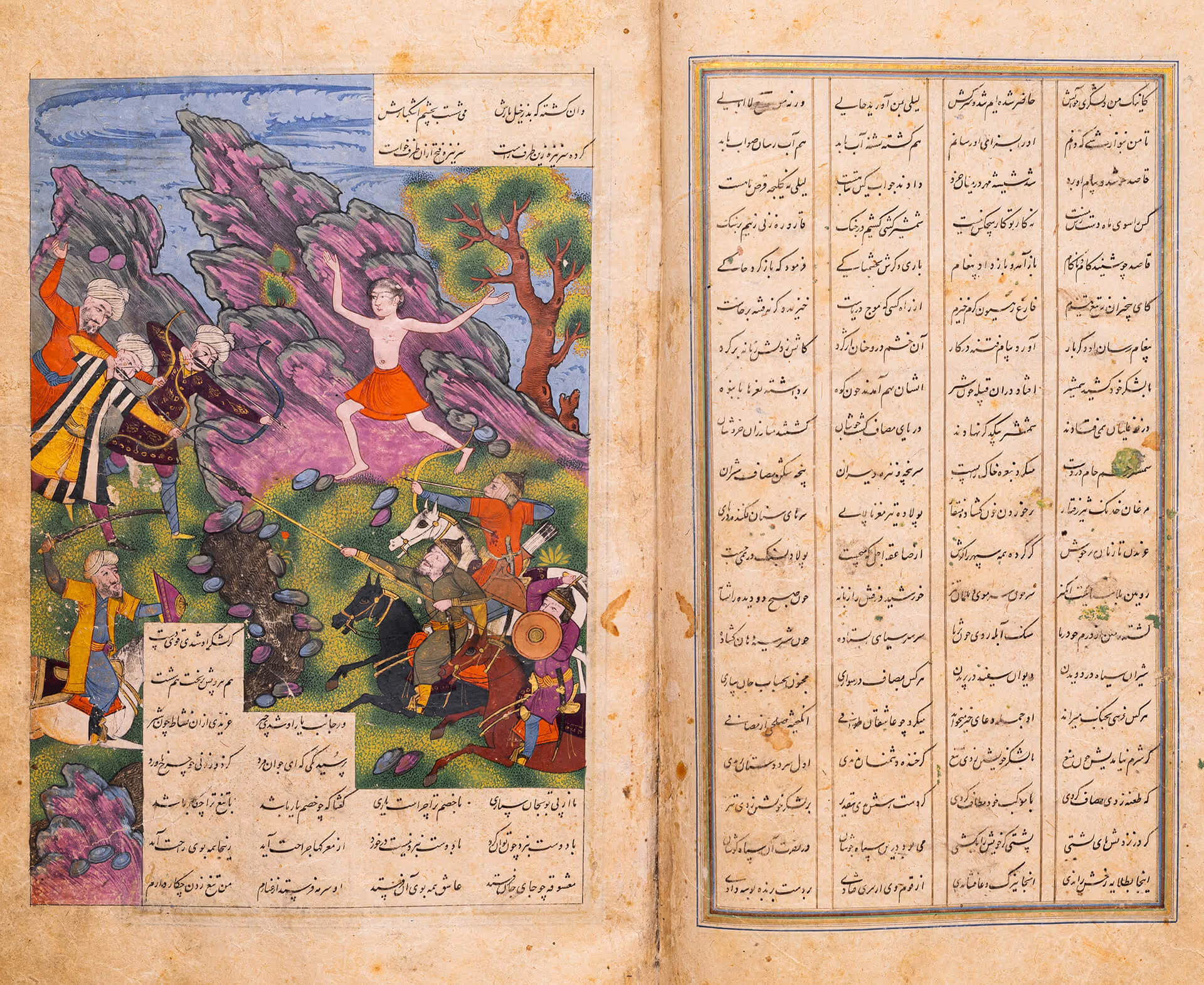

Some of the illustrations are rather amusing. The wise son is seen picking his nose. This could be a play on the words of the response he receives "and you should say to him" [v'af ata emor lo – af in Hebrew also means nose].

Another strange illustration appears underneath the song Dayeinu. The illustration depicts a gentile drinking himself into inebriation and warming his bare feet next to a fire, upon which he is roasting raw meat which does not seem particularly kosher.

One of these Haggadot contains some fifty pages written in quadratic Ashkenazi script, accompanied by dozens of colorful illustrations. Some of the wonderful illustrations in this Haggadah are connected to the text itself, and some contain motifs connected to the Haggadah and the story of the Exodus from Egypt – the ten plagues, matzah baking, and more.

This Haggadah would later become known as the "Rothschild Haggadah." Some of the illustrations in the Haggadah provide details regarding its source. The cities of Pithom and Ramses feature late gothic architecture, reminiscent of Northern Italian fortresses. The figures depicted in the Haggadah are also dressed in clothing typical of Northern Italy. The illustrator's name does not appear, but the style is reminiscent of that of a famous illustrator named Yoel Ben Shimon. Information taken from other manuscripts indicates that Yoel Ben Shimon was active in the second half of the 15th century in the cities of Modena and Cremona in Northern Italy.

Some of the illustrations are rather amusing. The wise son is seen picking his nose. This could be a play on the words of the response he receives "and you should say to him" [v'af ata emor lo – af in Hebrew also means nose].

Another strange illustration appears underneath the song Dayeinu. The illustration depicts a gentile drinking himself into inebriation and warming his bare feet next to a fire, upon which he is roasting raw meat which does not seem particularly kosher.

One of these Haggadot contains some fifty pages written in quadratic Ashkenazi script, accompanied by dozens of colorful illustrations. Some of the wonderful illustrations in this Haggadah are connected to the text itself, and some contain motifs connected to the Haggadah and the story of the Exodus from Egypt – the ten plagues, matzah baking, and more.

This Haggadah would later become known as the "Rothschild Haggadah." Some of the illustrations in the Haggadah provide details regarding its source. The cities of Pithom and Ramses feature late gothic architecture, reminiscent of Northern Italian fortresses. The figures depicted in the Haggadah are also dressed in clothing typical of Northern Italy. The illustrator's name does not appear, but the style is reminiscent of that of a famous illustrator named Yoel Ben Shimon. Information taken from other manuscripts indicates that Yoel Ben Shimon was active in the second half of the 15th century in the cities of Modena and Cremona in Northern Italy.

Some of the illustrations are rather amusing. The wise son is seen picking his nose. This could be a play on the words of the response he receives "and you should say to him" [v'af ata emor lo – af in Hebrew also means nose].

Another strange illustration appears underneath the song Dayeinu. The illustration depicts a gentile drinking himself into inebriation and warming his bare feet next to a fire, upon which he is roasting raw meat which does not seem particularly kosher.

Let's now jump forward in time, from the 15th century to World War II.

When the Nazis entered Paris on June 14, 1940, they immediately set their sights on the local riches. The Nazi pillagers mainly stole property of entities marked as "hostile," such as Jews. A short time after the occupation was completed, the chief ideologue of the Nazi party, Alfred Rosenberg, sent two representatives to locate and collect libraries of such "hostile entities". They were Walter Grothe – director of the Central Library at the Advanced School of the NSDAP (Hohe Schule der NSDAP), and Wilhelm Grau – director of the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question in Frankfurt.

Maurice Rothschild hid the manuscripts in his possession in a safe in a Parisian bank. On January 21, 1941 the Nazis broke into the bank safe and removed the treasures. A German officer left a receipt in the bank which stated the date and wrote that six crates had been taken. The Germans then went to the Rothschild estate where they continued their looting. Among the manuscripts taken was James Rothschild's illustrated Haggadah.

Let's now jump forward in time, from the 15th century to World War II.

When the Nazis entered Paris on June 14, 1940, they immediately set their sights on the local riches. The Nazi pillagers mainly stole property of entities marked as "hostile," such as Jews. A short time after the occupation was completed, the chief ideologue of the Nazi party, Alfred Rosenberg, sent two representatives to locate and collect libraries of such "hostile entities". They were Walter Grothe – director of the Central Library at the Advanced School of the NSDAP (Hohe Schule der NSDAP), and Wilhelm Grau – director of the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question in Frankfurt.

Maurice Rothschild hid the manuscripts in his possession in a safe in a Parisian bank. On January 21, 1941 the Nazis broke into the bank safe and removed the treasures. A German officer left a receipt in the bank which stated the date and wrote that six crates had been taken. The Germans then went to the Rothschild estate where they continued their looting. Among the manuscripts taken was James Rothschild's illustrated Haggadah.

Let's now jump forward in time, from the 15th century to World War II.

When the Nazis entered Paris on June 14, 1940, they immediately set their sights on the local riches. The Nazi pillagers mainly stole property of entities marked as "hostile," such as Jews. A short time after the occupation was completed, the chief ideologue of the Nazi party, Alfred Rosenberg, sent two representatives to locate and collect libraries of such "hostile entities". They were Walter Grothe – director of the Central Library at the Advanced School of the NSDAP (Hohe Schule der NSDAP), and Wilhelm Grau – director of the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question in Frankfurt.

Maurice Rothschild hid the manuscripts in his possession in a safe in a Parisian bank. On January 21, 1941 the Nazis broke into the bank safe and removed the treasures. A German officer left a receipt in the bank which stated the date and wrote that six crates had been taken. The Germans then went to the Rothschild estate where they continued their looting. Among the manuscripts taken was James Rothschild's illustrated Haggadah.

The books stolen from the Rothschild family were sent to Germany, along with hundreds of thousands of other books taken from libraries throughout Western Europe. There they were divided between the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question and the Central Library and sorting center of the Advanced School of the NSDAP.

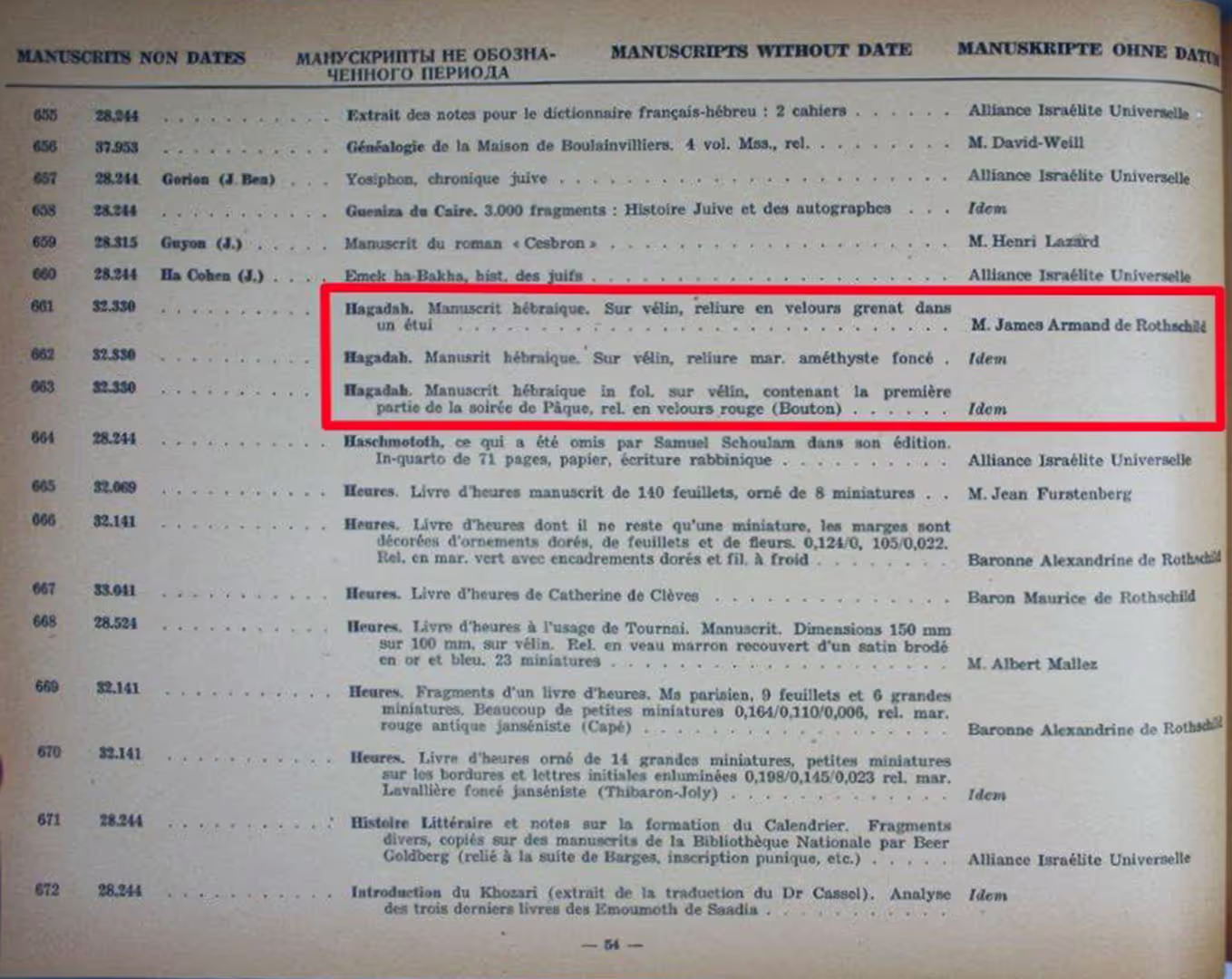

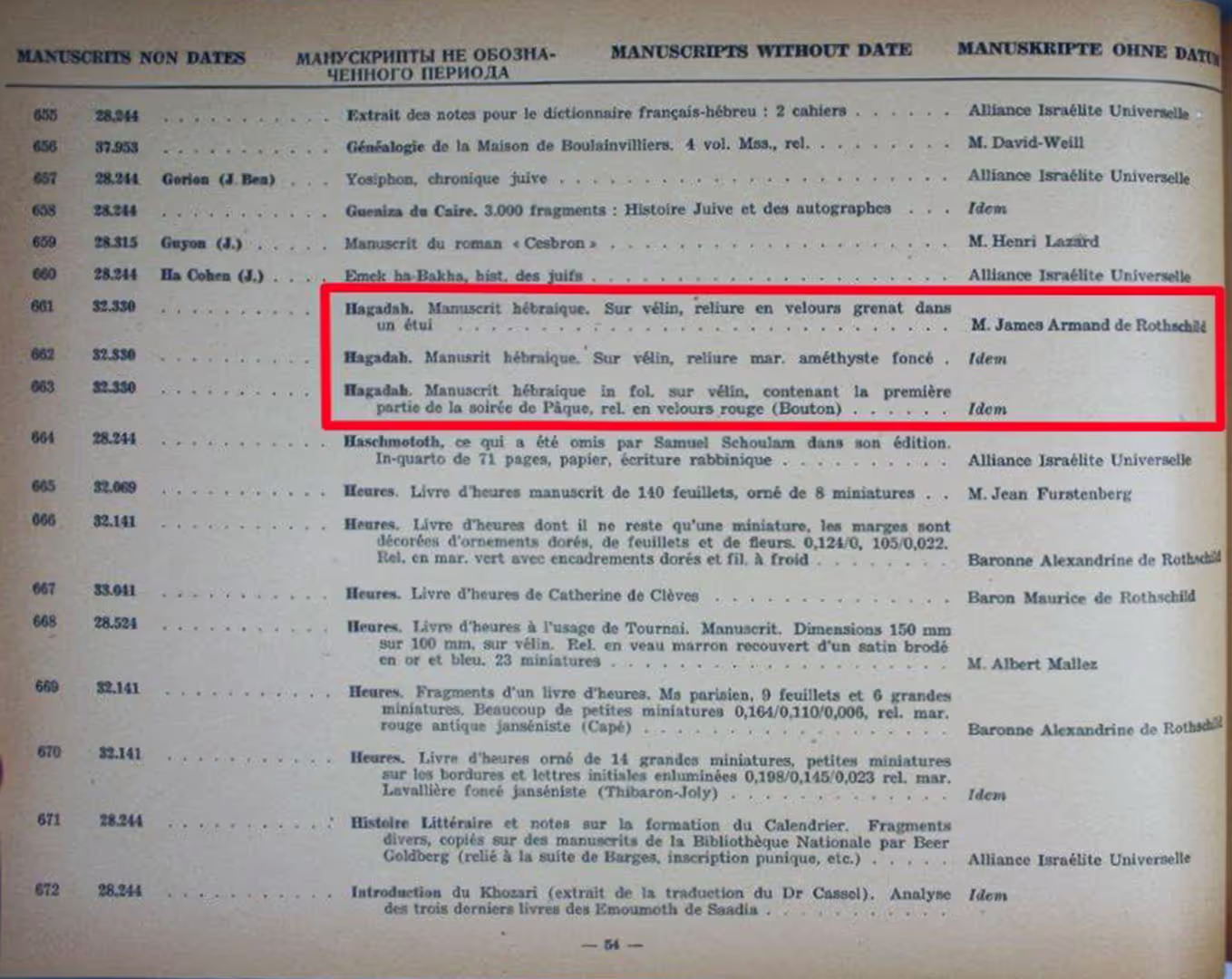

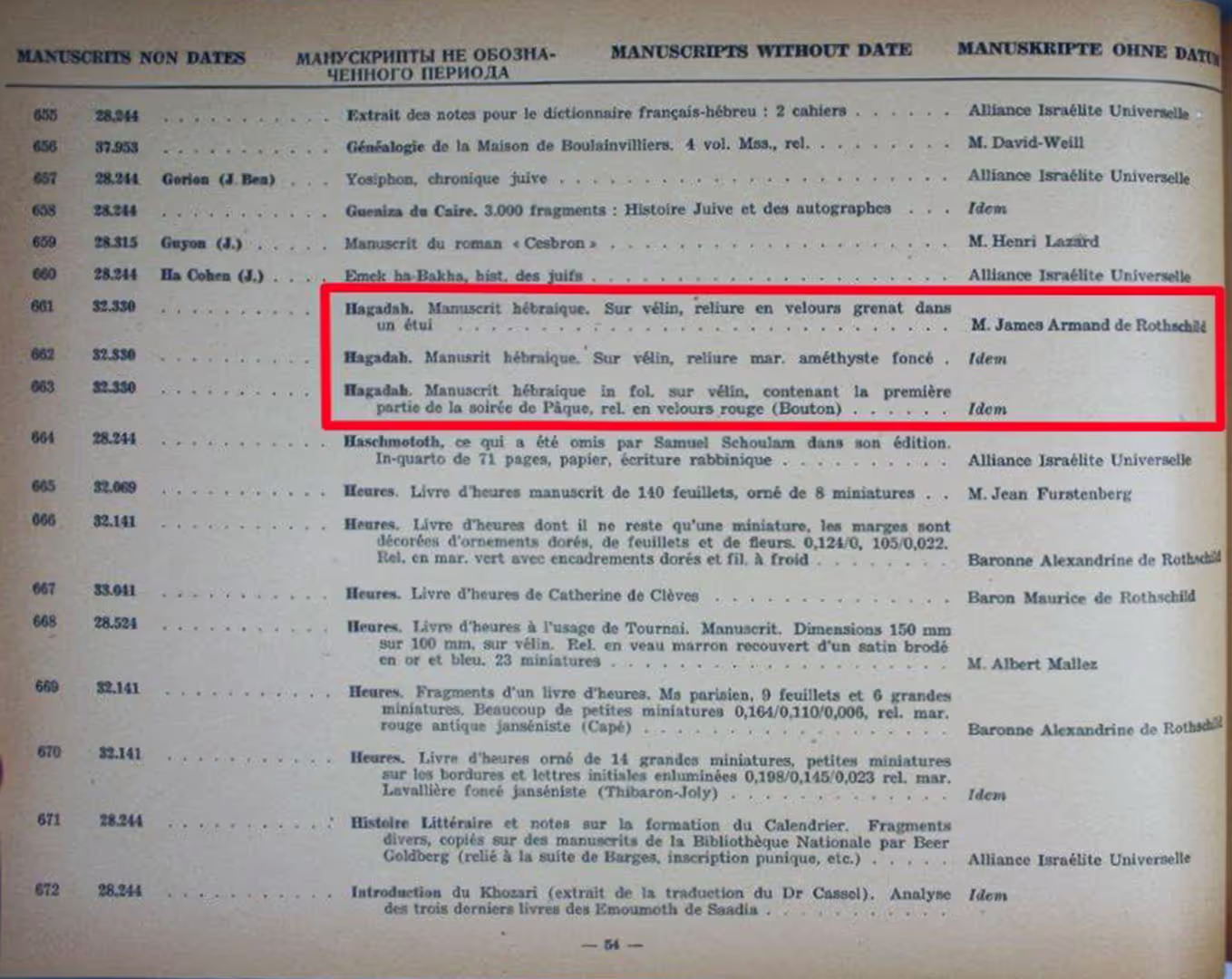

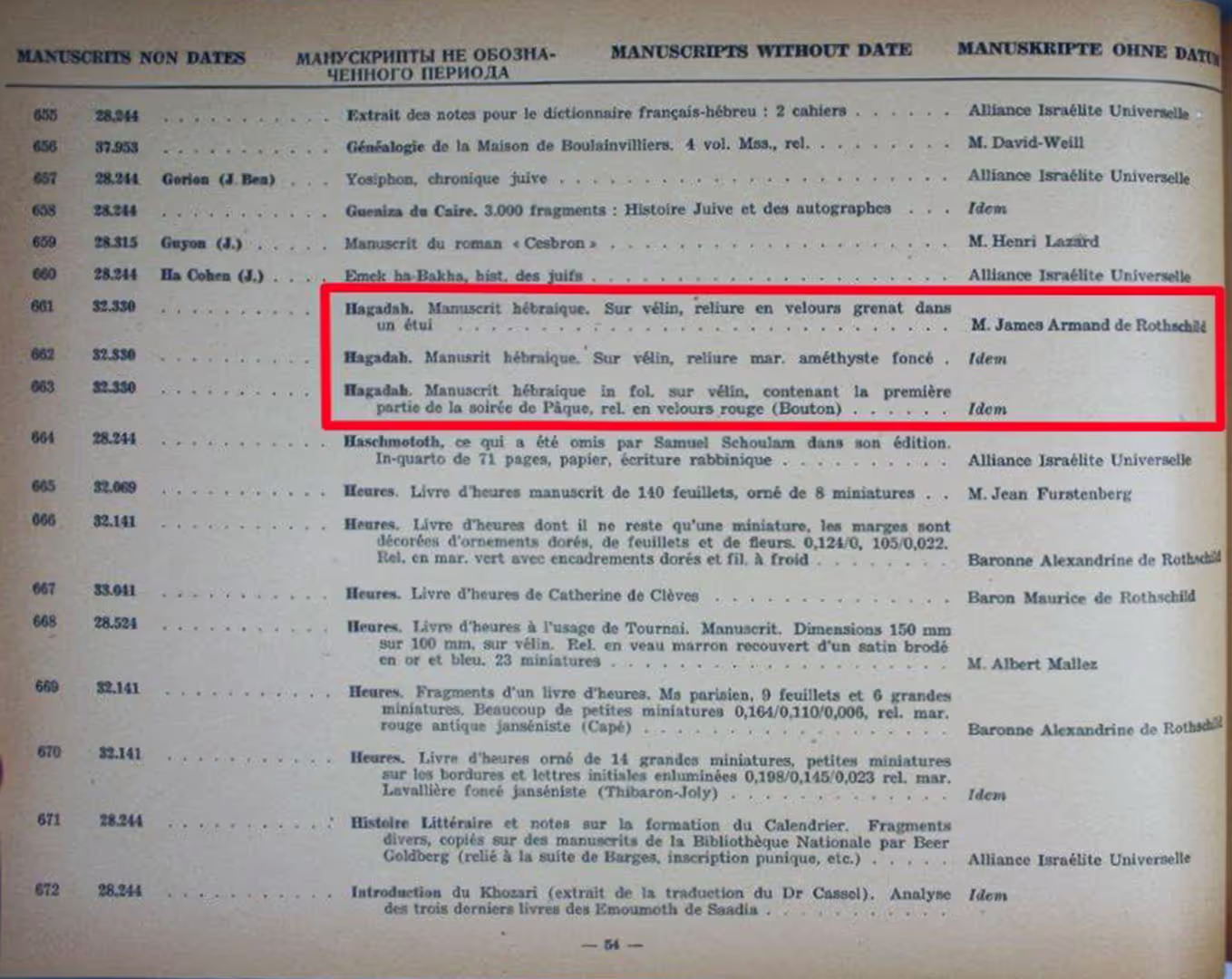

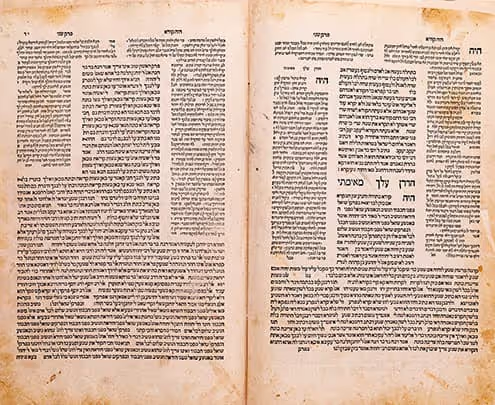

After the war, the French army published a series of thick volumes with lists of artworks stolen by the Nazis. The three Rothschild siblings sent lists of manuscripts stolen from their collections, which can be seen in the seventh volume.

The books stolen from the Rothschild family were sent to Germany, along with hundreds of thousands of other books taken from libraries throughout Western Europe. There they were divided between the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question and the Central Library and sorting center of the Advanced School of the NSDAP.

After the war, the French army published a series of thick volumes with lists of artworks stolen by the Nazis. The three Rothschild siblings sent lists of manuscripts stolen from their collections, which can be seen in the seventh volume.

The books stolen from the Rothschild family were sent to Germany, along with hundreds of thousands of other books taken from libraries throughout Western Europe. There they were divided between the Institute for Study of the Jewish Question and the Central Library and sorting center of the Advanced School of the NSDAP.

After the war, the French army published a series of thick volumes with lists of artworks stolen by the Nazis. The three Rothschild siblings sent lists of manuscripts stolen from their collections, which can be seen in the seventh volume.

Years passed, and only some of the manuscripts were found and returned to James, Maurice and Miriam.

In 1948 Dr. Fred Murphy bequeathed a Haggadah which had come into his possession to the rare books collection of Yale University. The university came to refer to the manuscript as the "Murphy Haggadah", after its donor.

On the back page of the binding of the manuscript is a small simple stamp of the name William V. Black. Information from the genealogy website My Heritage indicates that several soldiers with this name served in the Second World War. This Haggadah may have been found by an American soldier with this name (or another) who brought it back from Europe following the war's conclusion. Perhaps Professor Murphy received it from him.

It was not until 1980 that Professor James Marrow, a researcher of art history at Princeton University, identified the item as one of James Rothschild's lost Haggadot. James had died in 1957, so Yale University gave the Haggadah to his widow Dorothy in England. Baroness Dorothy decided to bequeath the valuable manuscript to the National Library in Jerusalem.

Three leaves were missing from the Haggadah. Two of them contained the end of the "Kadesh", "Urchatz", and "Karpas" sections and the beginning of the "Maggid" section of the Seder service.

In 2007, two illustrated leaves of a Passover Haggadah were auctioned in France. The antique dealer who bought them sent them to Jerusalem to be examined. In 2008, Dr. Evelyn Cohen, an expert in illustrated Jewish manuscripts, identified the two leaves as the missing leaves of the "Rothschild Haggadah". The leaves were purchased for the National Library and returned to their rightful place in the Passover Haggadah.

The long journey, which began 550 years ago with the illustrator Yoel Ben Shimon in Northern Italy, finally ended with the Haggadah being scanned by the National Library in Jerusalem, making it accessible to anyone who wishes to see it.

View this item in the NLI catalog

Years passed, and only some of the manuscripts were found and returned to James, Maurice and Miriam.

In 1948 Dr. Fred Murphy bequeathed a Haggadah which had come into his possession to the rare books collection of Yale University. The university came to refer to the manuscript as the "Murphy Haggadah", after its donor.

On the back page of the binding of the manuscript is a small simple stamp of the name William V. Black. Information from the genealogy website My Heritage indicates that several soldiers with this name served in the Second World War. This Haggadah may have been found by an American soldier with this name (or another) who brought it back from Europe following the war's conclusion. Perhaps Professor Murphy received it from him.

It was not until 1980 that Professor James Marrow, a researcher of art history at Princeton University, identified the item as one of James Rothschild's lost Haggadot. James had died in 1957, so Yale University gave the Haggadah to his widow Dorothy in England. Baroness Dorothy decided to bequeath the valuable manuscript to the National Library in Jerusalem.

Three leaves were missing from the Haggadah. Two of them contained the end of the "Kadesh", "Urchatz", and "Karpas" sections and the beginning of the "Maggid" section of the Seder service.

In 2007, two illustrated leaves of a Passover Haggadah were auctioned in France. The antique dealer who bought them sent them to Jerusalem to be examined. In 2008, Dr. Evelyn Cohen, an expert in illustrated Jewish manuscripts, identified the two leaves as the missing leaves of the "Rothschild Haggadah". The leaves were purchased for the National Library and returned to their rightful place in the Passover Haggadah.

The long journey, which began 550 years ago with the illustrator Yoel Ben Shimon in Northern Italy, finally ended with the Haggadah being scanned by the National Library in Jerusalem, making it accessible to anyone who wishes to see it.

View this item in the NLI catalog

Years passed, and only some of the manuscripts were found and returned to James, Maurice and Miriam.

In 1948 Dr. Fred Murphy bequeathed a Haggadah which had come into his possession to the rare books collection of Yale University. The university came to refer to the manuscript as the "Murphy Haggadah", after its donor.

On the back page of the binding of the manuscript is a small simple stamp of the name William V. Black. Information from the genealogy website My Heritage indicates that several soldiers with this name served in the Second World War. This Haggadah may have been found by an American soldier with this name (or another) who brought it back from Europe following the war's conclusion. Perhaps Professor Murphy received it from him.

It was not until 1980 that Professor James Marrow, a researcher of art history at Princeton University, identified the item as one of James Rothschild's lost Haggadot. James had died in 1957, so Yale University gave the Haggadah to his widow Dorothy in England. Baroness Dorothy decided to bequeath the valuable manuscript to the National Library in Jerusalem.

Three leaves were missing from the Haggadah. Two of them contained the end of the "Kadesh", "Urchatz", and "Karpas" sections and the beginning of the "Maggid" section of the Seder service.

In 2007, two illustrated leaves of a Passover Haggadah were auctioned in France. The antique dealer who bought them sent them to Jerusalem to be examined. In 2008, Dr. Evelyn Cohen, an expert in illustrated Jewish manuscripts, identified the two leaves as the missing leaves of the "Rothschild Haggadah". The leaves were purchased for the National Library and returned to their rightful place in the Passover Haggadah.

The long journey, which began 550 years ago with the illustrator Yoel Ben Shimon in Northern Italy, finally ended with the Haggadah being scanned by the National Library in Jerusalem, making it accessible to anyone who wishes to see it.

View this item in the NLI catalog

tab1img1="The Famous Benefactor" Edmond de Rothschild

tab2img1=Ma Nishtana (The Four Questions) from the Rothschild Haggadah

tab2img2=The wise son, from the Rothschild Haggadah

tab2img3=Dayeinu, from the Rothschild Haggadah

tab3img3=James Rothschild, son of "The Famous Benefactor"

tab4img2=The Rothschild Haggadah is cited in the seventh volume

.avif)

.svg)