An Illustrated Treasure: The Original Latin Version of the Bible

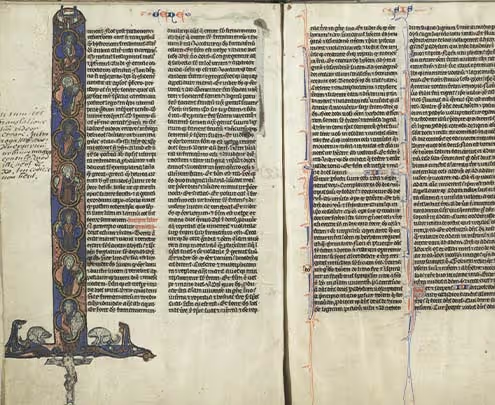

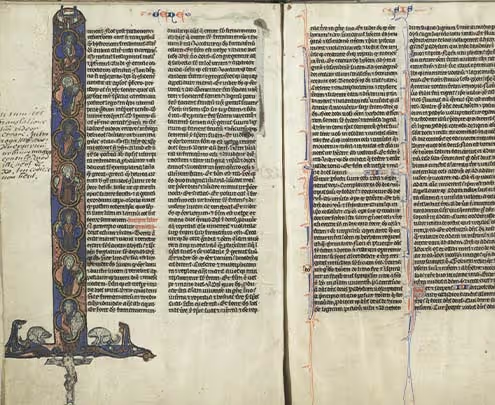

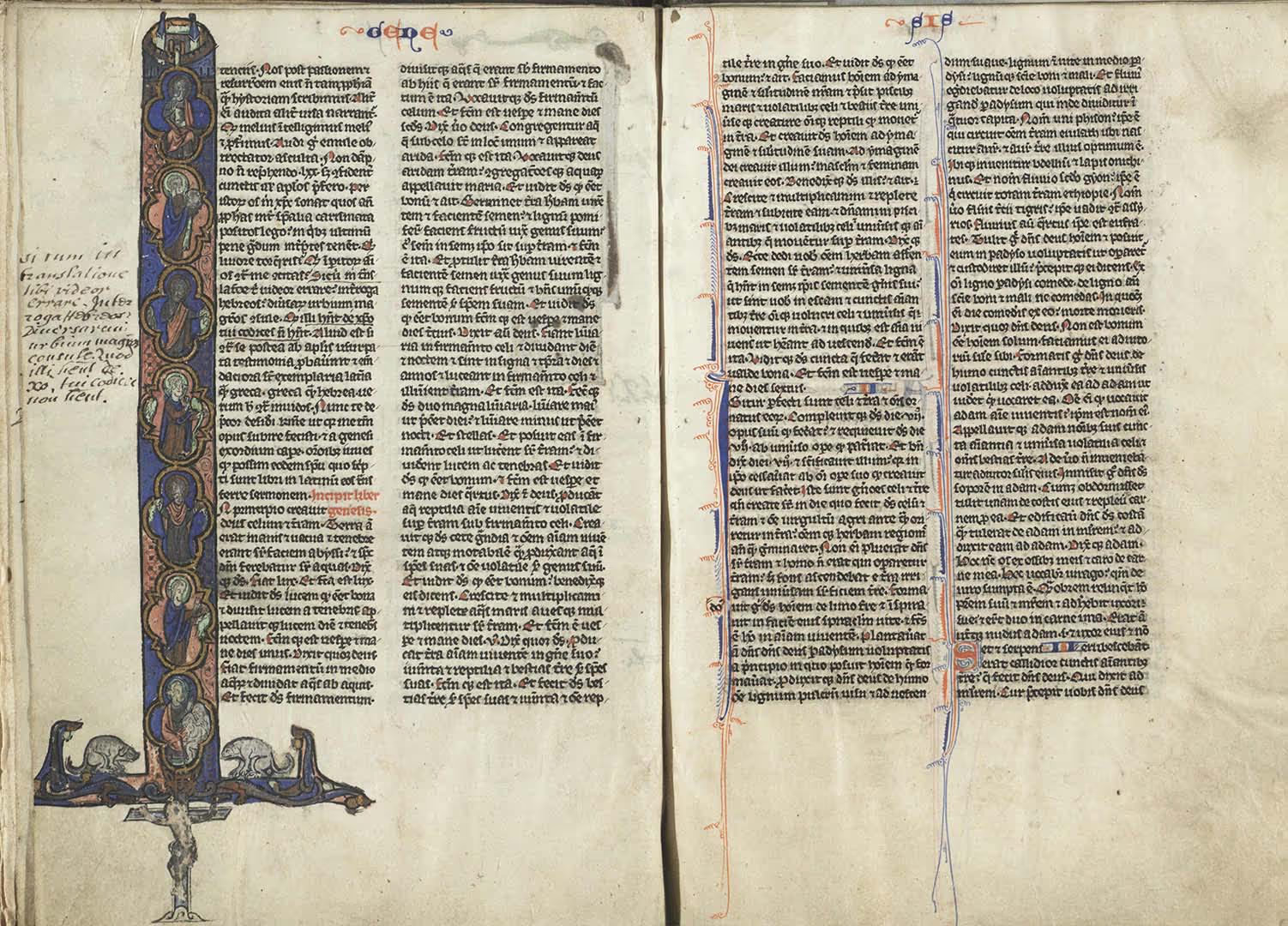

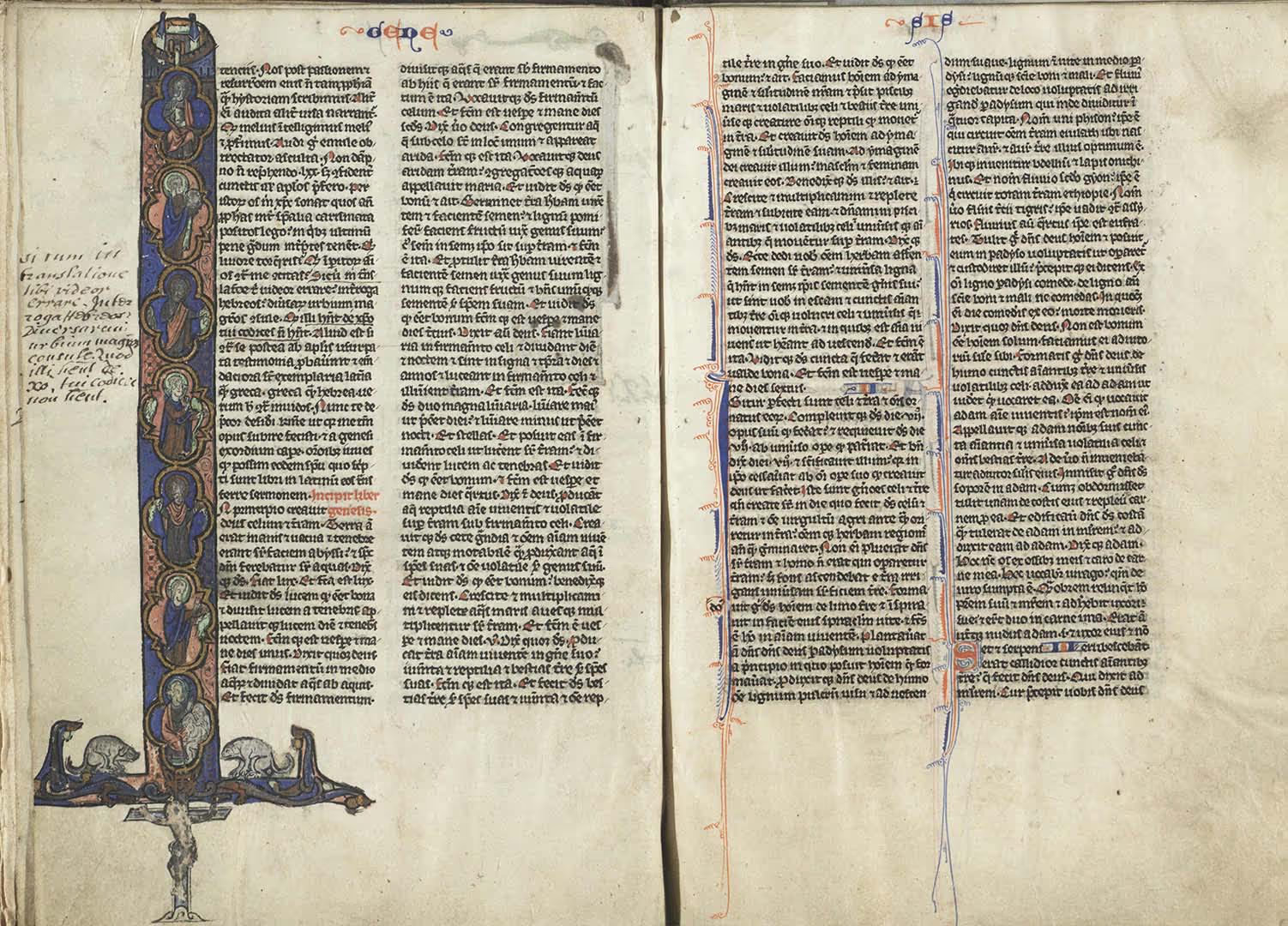

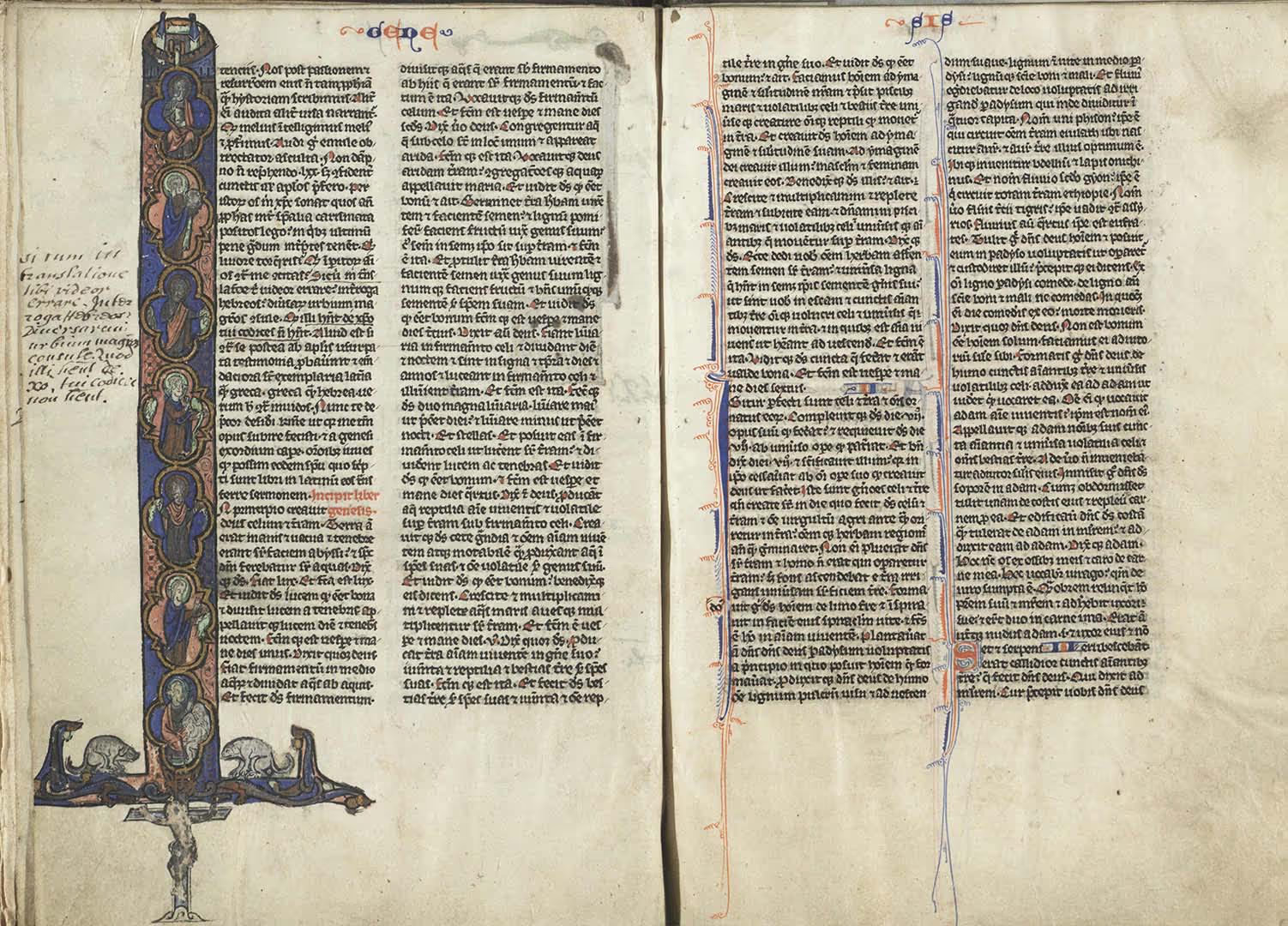

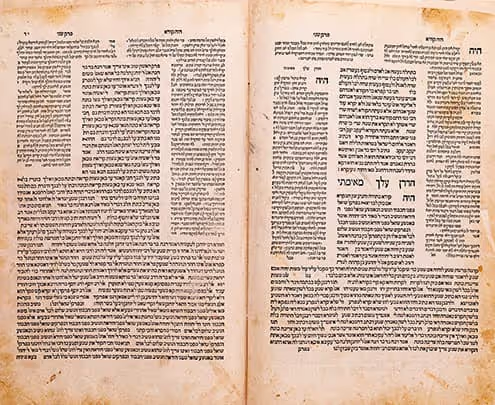

One of the most intriguing items kept in the National Library of Israel is a copy of the Vulgate, which was illustrated on parchment and created in the middle of the 13th century. The Vulgate is the Latin translation of the Bible. It includes several books that are not part of the Hebrew canon (the Tankach) and this copy is considered a rare treasure in the world of Christian scripture.

The translation of Christian religious scriptures into Latin began in the 2nd century CE, if not earlier. These early translations were composed by Jewish exiles who had come from Judea after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and they reflect Jewish tradition. These translations were generally partial and were based on the Septuagint (the translation of the Bible into ancient Greek). They were written in Latin, enriched with words borrowed from Hebrew.

Over time, some changes were made to the nature of these translations into Latin: the bulk of work shifted from Jewish hands to Christian ones, emphasis was placed on translating the New Testament, and translation centers were established in Spain and North Africa. In 382 CE, Pope Damasus I appointed the priest Jerome to correct and edit existing translations of the Four Gospels of the New Testament, as well as the Book of Psalms.

Jerome began working on the translation in 390 CE, and he completed it in 405 CE. He had mastered Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and in his translation, he relied on various sources and versions. In addition to editing the translations, he translated the books of the Tanakh himself, according to a Hebrew version that was similar to the Masoretic Text.

One of the most intriguing items kept in the National Library of Israel is a copy of the Vulgate, which was illustrated on parchment and created in the middle of the 13th century. The Vulgate is the Latin translation of the Bible. It includes several books that are not part of the Hebrew canon (the Tankach) and this copy is considered a rare treasure in the world of Christian scripture.

The translation of Christian religious scriptures into Latin began in the 2nd century CE, if not earlier. These early translations were composed by Jewish exiles who had come from Judea after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and they reflect Jewish tradition. These translations were generally partial and were based on the Septuagint (the translation of the Bible into ancient Greek). They were written in Latin, enriched with words borrowed from Hebrew.

Over time, some changes were made to the nature of these translations into Latin: the bulk of work shifted from Jewish hands to Christian ones, emphasis was placed on translating the New Testament, and translation centers were established in Spain and North Africa. In 382 CE, Pope Damasus I appointed the priest Jerome to correct and edit existing translations of the Four Gospels of the New Testament, as well as the Book of Psalms.

Jerome began working on the translation in 390 CE, and he completed it in 405 CE. He had mastered Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and in his translation, he relied on various sources and versions. In addition to editing the translations, he translated the books of the Tanakh himself, according to a Hebrew version that was similar to the Masoretic Text.

One of the most intriguing items kept in the National Library of Israel is a copy of the Vulgate, which was illustrated on parchment and created in the middle of the 13th century. The Vulgate is the Latin translation of the Bible. It includes several books that are not part of the Hebrew canon (the Tankach) and this copy is considered a rare treasure in the world of Christian scripture.

The translation of Christian religious scriptures into Latin began in the 2nd century CE, if not earlier. These early translations were composed by Jewish exiles who had come from Judea after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and they reflect Jewish tradition. These translations were generally partial and were based on the Septuagint (the translation of the Bible into ancient Greek). They were written in Latin, enriched with words borrowed from Hebrew.

Over time, some changes were made to the nature of these translations into Latin: the bulk of work shifted from Jewish hands to Christian ones, emphasis was placed on translating the New Testament, and translation centers were established in Spain and North Africa. In 382 CE, Pope Damasus I appointed the priest Jerome to correct and edit existing translations of the Four Gospels of the New Testament, as well as the Book of Psalms.

Jerome began working on the translation in 390 CE, and he completed it in 405 CE. He had mastered Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and in his translation, he relied on various sources and versions. In addition to editing the translations, he translated the books of the Tanakh himself, according to a Hebrew version that was similar to the Masoretic Text.

Jerome’s translation was known as the Biblia Vulgata ("the Bible in common tongue") or “Vulgate”. It became the accepted version of the Bible in Europe in the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church even recognized it as the official translation of the Old Testament. Like the Septuagint translation, the Vulgate includes the books of the Maccabees – two books that were written in the 2nd century BCE but were not preserved in Jewish sources. We only have these books in their Greek version from the Septuagint and their Latin version from the Vulgate. All other known translations are derived from these sources.

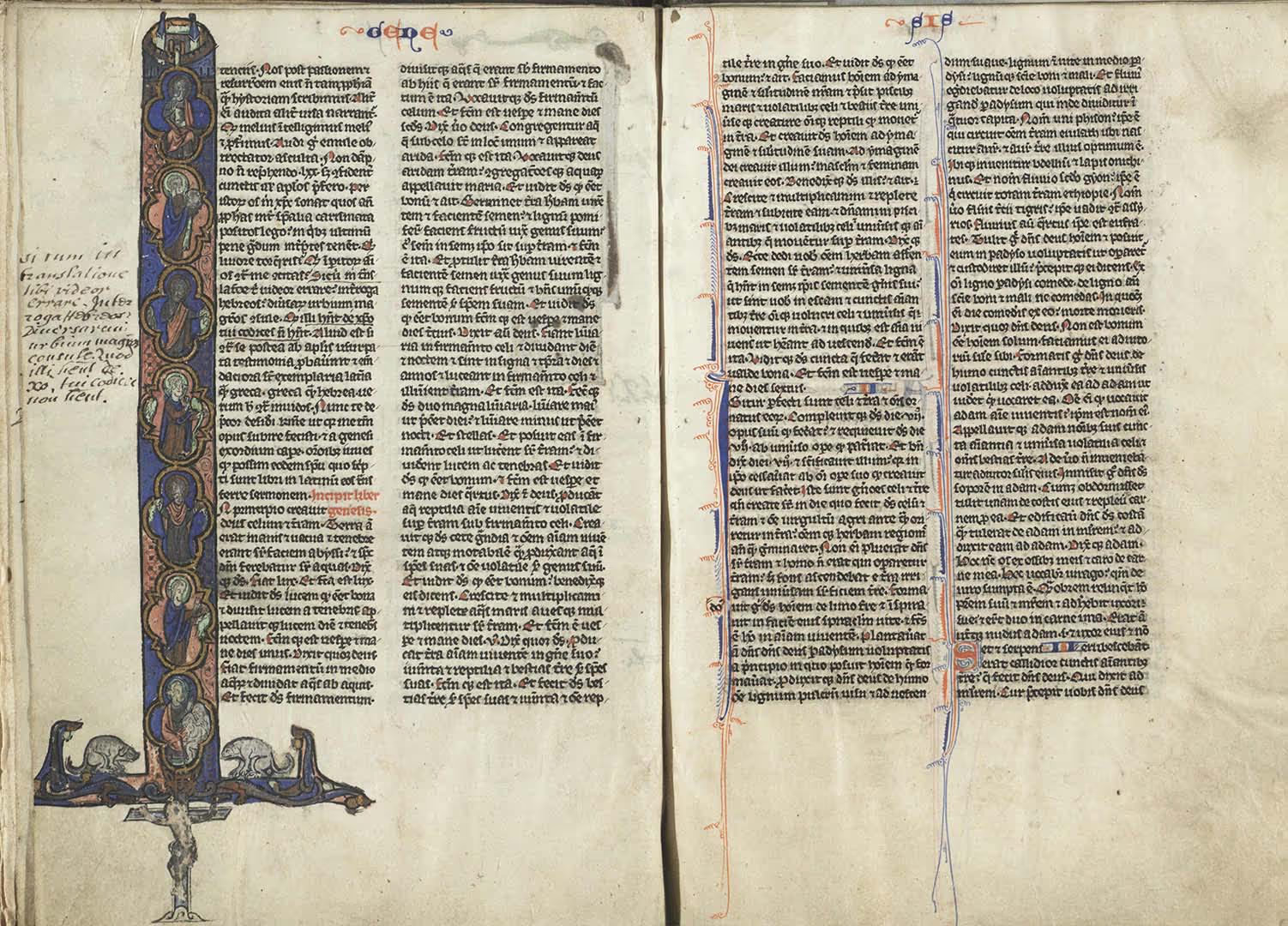

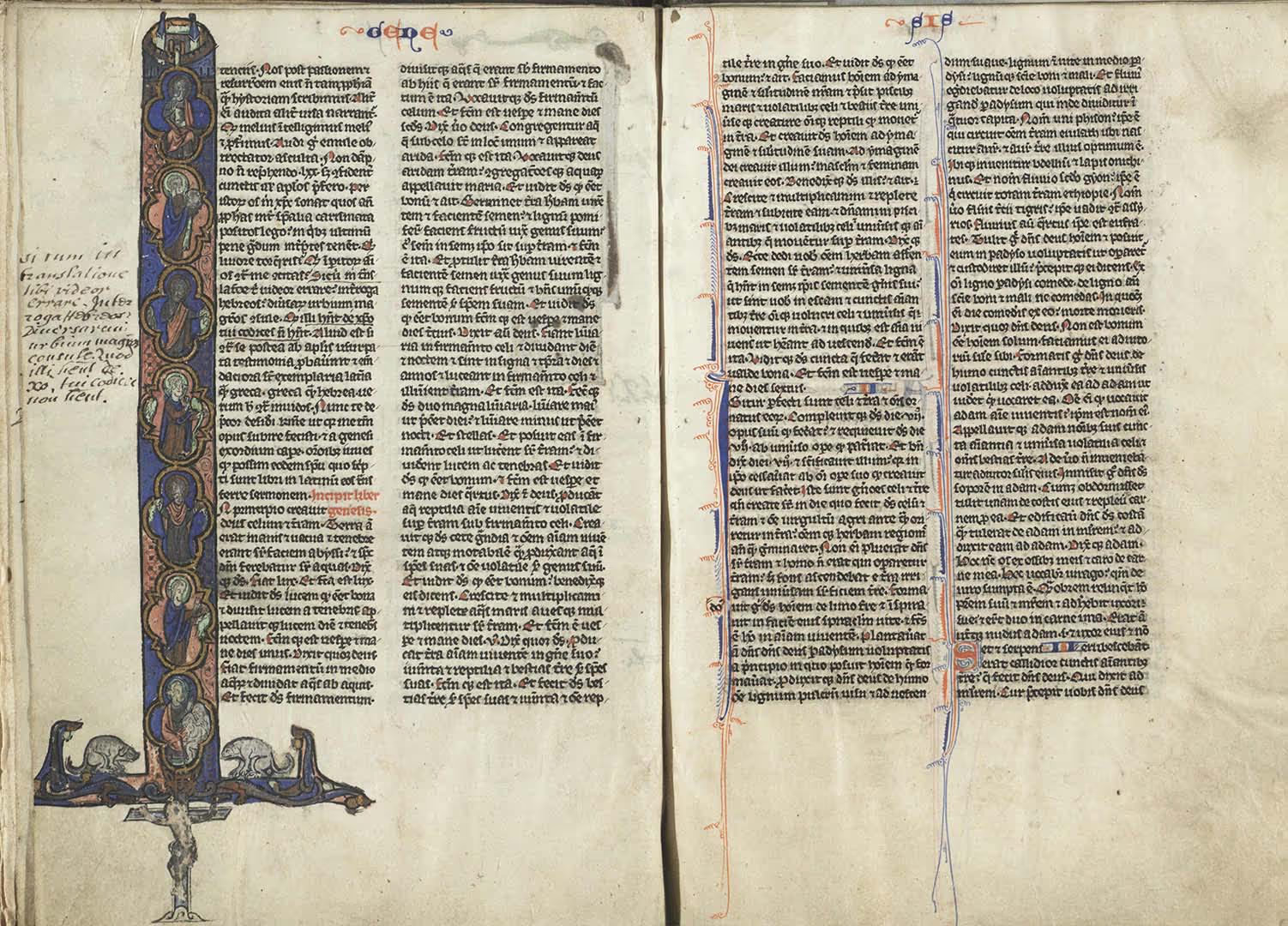

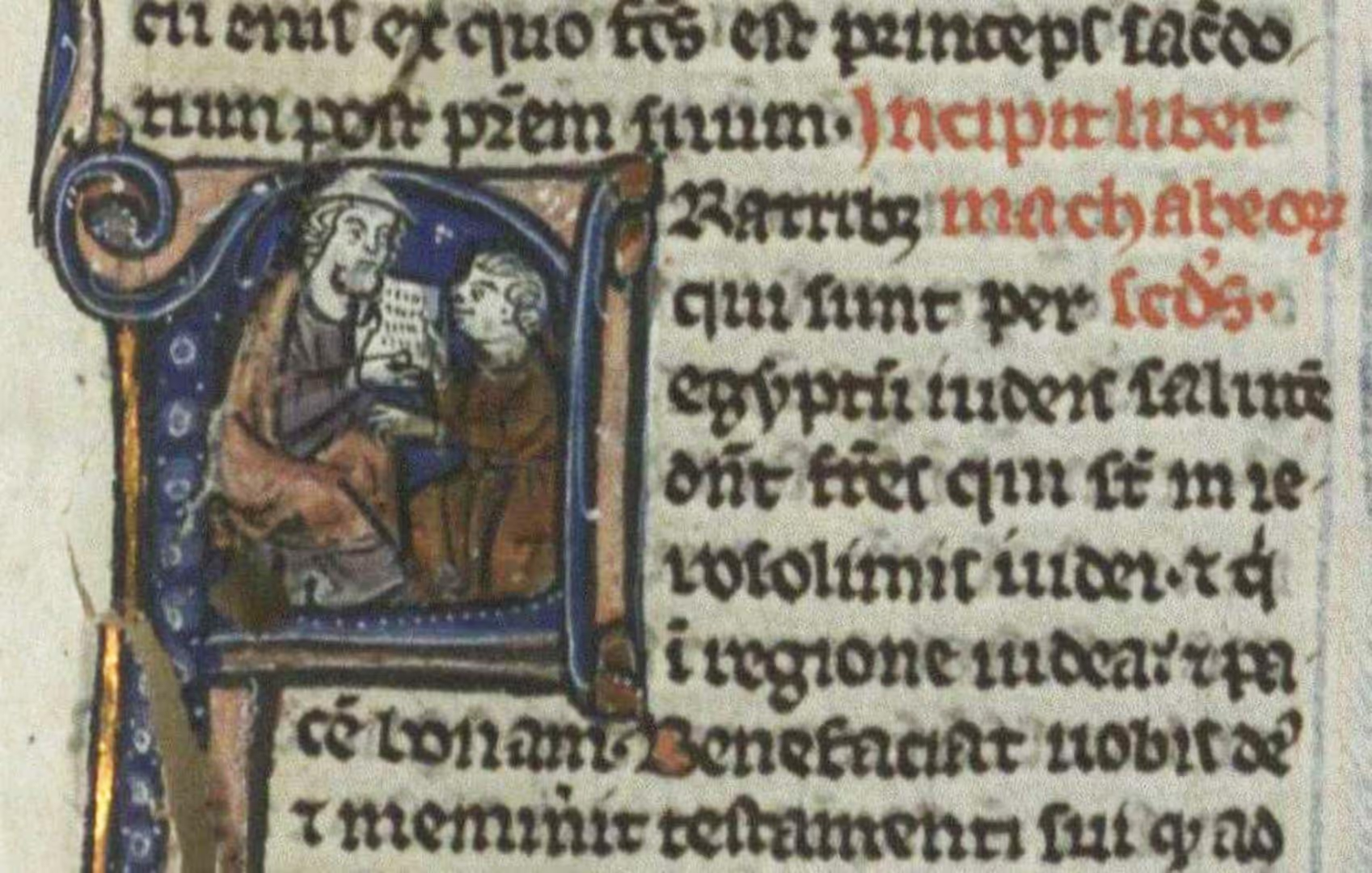

The illustrations in the copy of the Vulgate that is in the National Library are interesting in and of themselves. For example, in an illustration that appears alongside Psalm 5, Jerome the translator is seen working at his desk, next to the lion that faithfully accompanied him after Jerome healed his wounded leg, according to Christian tradition.

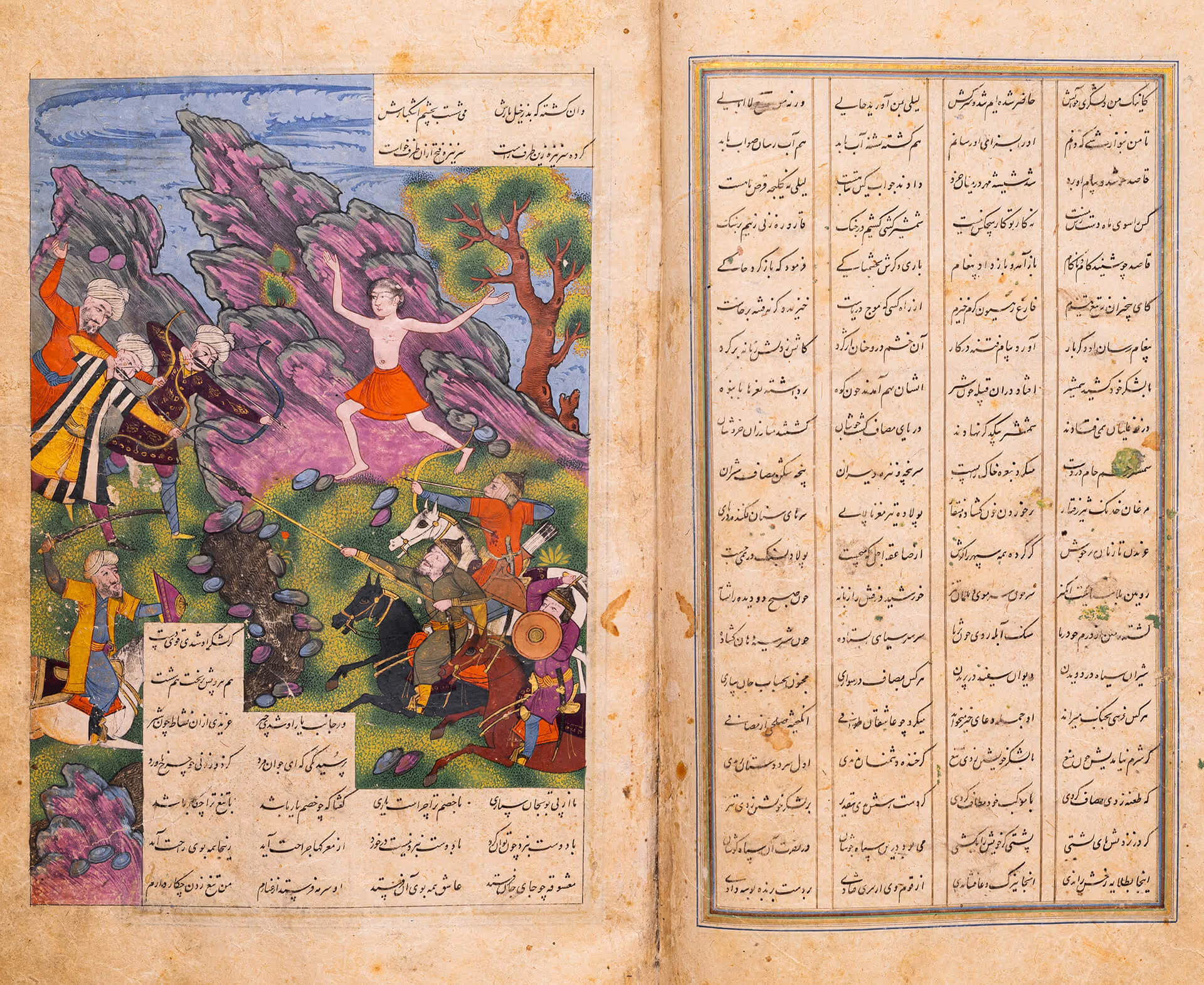

Another illustration, on Page 413, depicts an evil Greek who is holding a sword in one hand, as his other hand grasps the hair on the head of a priest who is kneeling down, with a ritual nesach goblet in his hand. The illustration apparently refers to Maccabees I, 1:45:

"He banned the regular practices of entirely burned offerings, sacrifices, and drink offerings in the sanctuary. He banned the observance of sabbaths and feast days"

Verse 57 continues: "If anyone was caught in possession of a copy of the covenant scroll or if anyone kept to the Law, that person was condemned to death by royal decree."

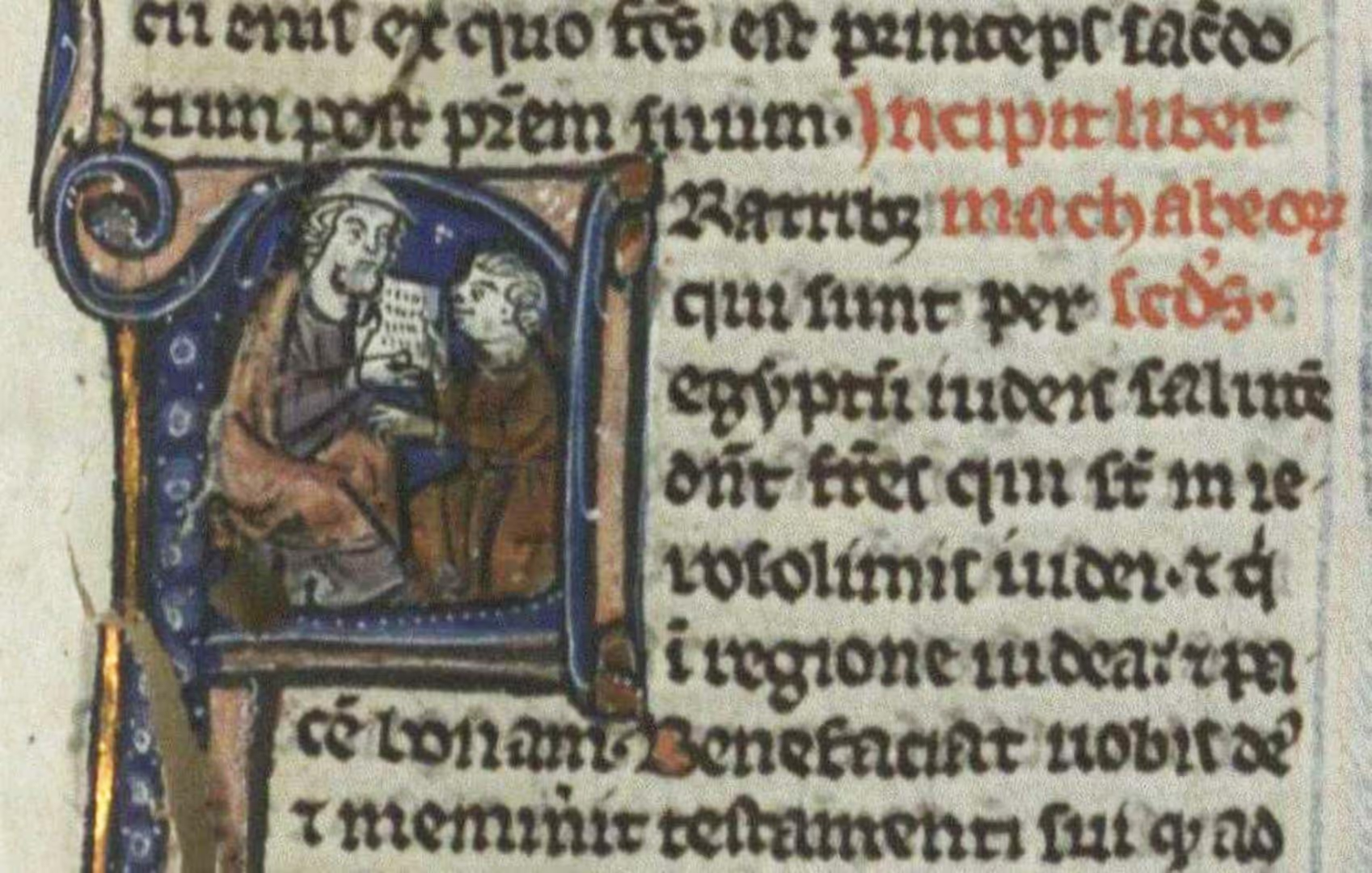

The illustrations of the Book of Maccabees II, on page 426, depict a Jew from Jerusalem who is seen handing letters to a messenger. In these letters, the Jews of Jerusalem tell the Jews of Alexandria about the holiday of Hanukkah, encouraging the latter to celebrate it. The letters were originally written in Hebrew, unlike the rest of the text in the Book of Maccabees II, and they were added to the book after it was written, in order to establish the Holiday of Hanukkah alongside the Day of Nicanor. The Day of Nicanor? Perhaps this holiday doesn't appear on your calendar, but this ancient Jewish festival did actually exist. It was marked on the 13th of Adar (which also happens to be the Fast of Esther), to commemorate the victory of the Judean army over Nicanor, a Seleucid general, as part of the Hasmonean Revolt in the year 161 BCE.

Jerome’s translation was known as the Biblia Vulgata ("the Bible in common tongue") or “Vulgate”. It became the accepted version of the Bible in Europe in the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church even recognized it as the official translation of the Old Testament. Like the Septuagint translation, the Vulgate includes the books of the Maccabees – two books that were written in the 2nd century BCE but were not preserved in Jewish sources. We only have these books in their Greek version from the Septuagint and their Latin version from the Vulgate. All other known translations are derived from these sources.

The illustrations in the copy of the Vulgate that is in the National Library are interesting in and of themselves. For example, in an illustration that appears alongside Psalm 5, Jerome the translator is seen working at his desk, next to the lion that faithfully accompanied him after Jerome healed his wounded leg, according to Christian tradition.

Another illustration, on Page 413, depicts an evil Greek who is holding a sword in one hand, as his other hand grasps the hair on the head of a priest who is kneeling down, with a ritual nesach goblet in his hand. The illustration apparently refers to Maccabees I, 1:45:

"He banned the regular practices of entirely burned offerings, sacrifices, and drink offerings in the sanctuary. He banned the observance of sabbaths and feast days"

Verse 57 continues: "If anyone was caught in possession of a copy of the covenant scroll or if anyone kept to the Law, that person was condemned to death by royal decree."

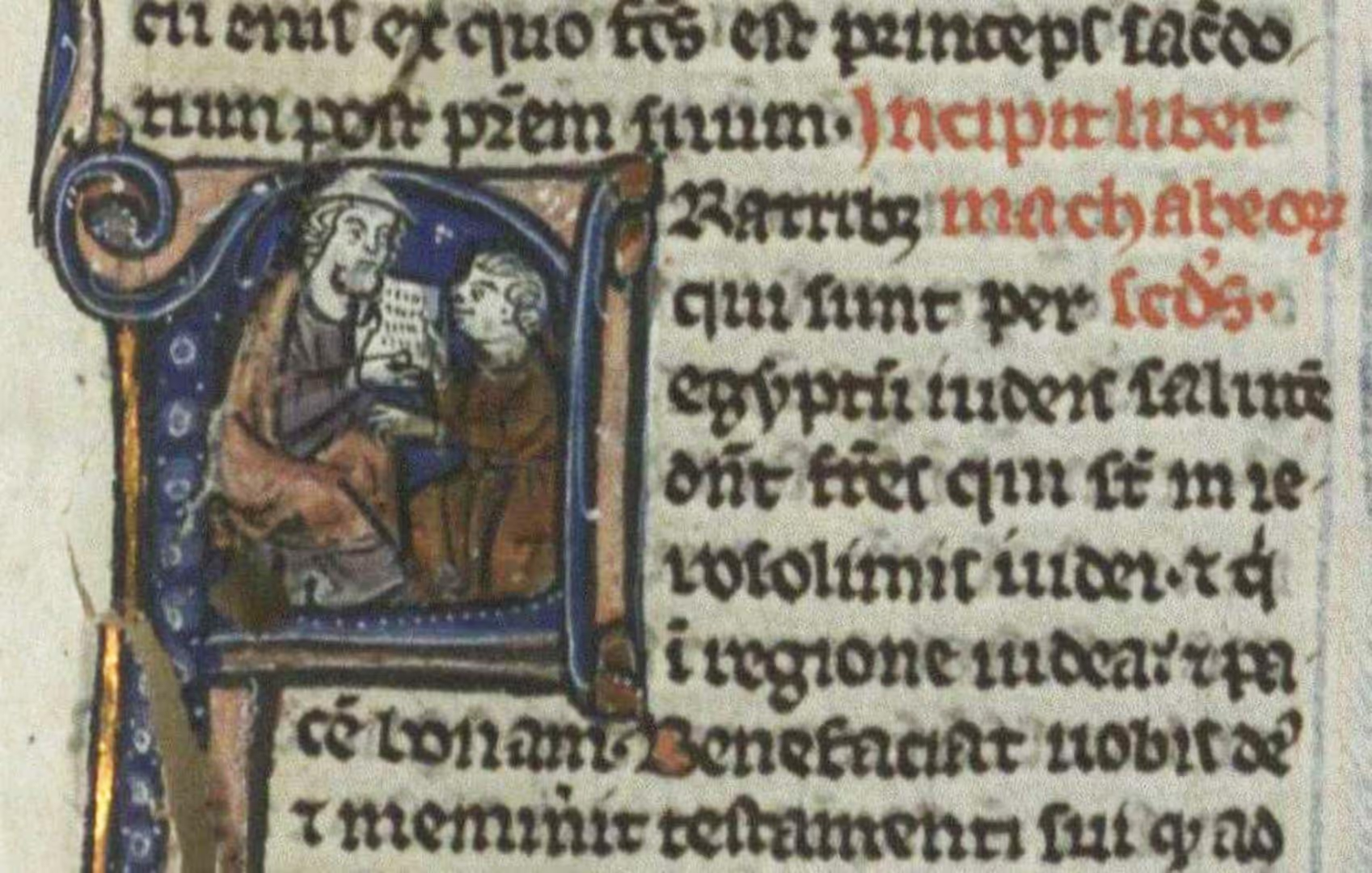

The illustrations of the Book of Maccabees II, on page 426, depict a Jew from Jerusalem who is seen handing letters to a messenger. In these letters, the Jews of Jerusalem tell the Jews of Alexandria about the holiday of Hanukkah, encouraging the latter to celebrate it. The letters were originally written in Hebrew, unlike the rest of the text in the Book of Maccabees II, and they were added to the book after it was written, in order to establish the Holiday of Hanukkah alongside the Day of Nicanor. The Day of Nicanor? Perhaps this holiday doesn't appear on your calendar, but this ancient Jewish festival did actually exist. It was marked on the 13th of Adar (which also happens to be the Fast of Esther), to commemorate the victory of the Judean army over Nicanor, a Seleucid general, as part of the Hasmonean Revolt in the year 161 BCE.

Jerome’s translation was known as the Biblia Vulgata ("the Bible in common tongue") or “Vulgate”. It became the accepted version of the Bible in Europe in the Middle Ages. The Catholic Church even recognized it as the official translation of the Old Testament. Like the Septuagint translation, the Vulgate includes the books of the Maccabees – two books that were written in the 2nd century BCE but were not preserved in Jewish sources. We only have these books in their Greek version from the Septuagint and their Latin version from the Vulgate. All other known translations are derived from these sources.

The illustrations in the copy of the Vulgate that is in the National Library are interesting in and of themselves. For example, in an illustration that appears alongside Psalm 5, Jerome the translator is seen working at his desk, next to the lion that faithfully accompanied him after Jerome healed his wounded leg, according to Christian tradition.

Another illustration, on Page 413, depicts an evil Greek who is holding a sword in one hand, as his other hand grasps the hair on the head of a priest who is kneeling down, with a ritual nesach goblet in his hand. The illustration apparently refers to Maccabees I, 1:45:

"He banned the regular practices of entirely burned offerings, sacrifices, and drink offerings in the sanctuary. He banned the observance of sabbaths and feast days"

Verse 57 continues: "If anyone was caught in possession of a copy of the covenant scroll or if anyone kept to the Law, that person was condemned to death by royal decree."

The illustrations of the Book of Maccabees II, on page 426, depict a Jew from Jerusalem who is seen handing letters to a messenger. In these letters, the Jews of Jerusalem tell the Jews of Alexandria about the holiday of Hanukkah, encouraging the latter to celebrate it. The letters were originally written in Hebrew, unlike the rest of the text in the Book of Maccabees II, and they were added to the book after it was written, in order to establish the Holiday of Hanukkah alongside the Day of Nicanor. The Day of Nicanor? Perhaps this holiday doesn't appear on your calendar, but this ancient Jewish festival did actually exist. It was marked on the 13th of Adar (which also happens to be the Fast of Esther), to commemorate the victory of the Judean army over Nicanor, a Seleucid general, as part of the Hasmonean Revolt in the year 161 BCE.

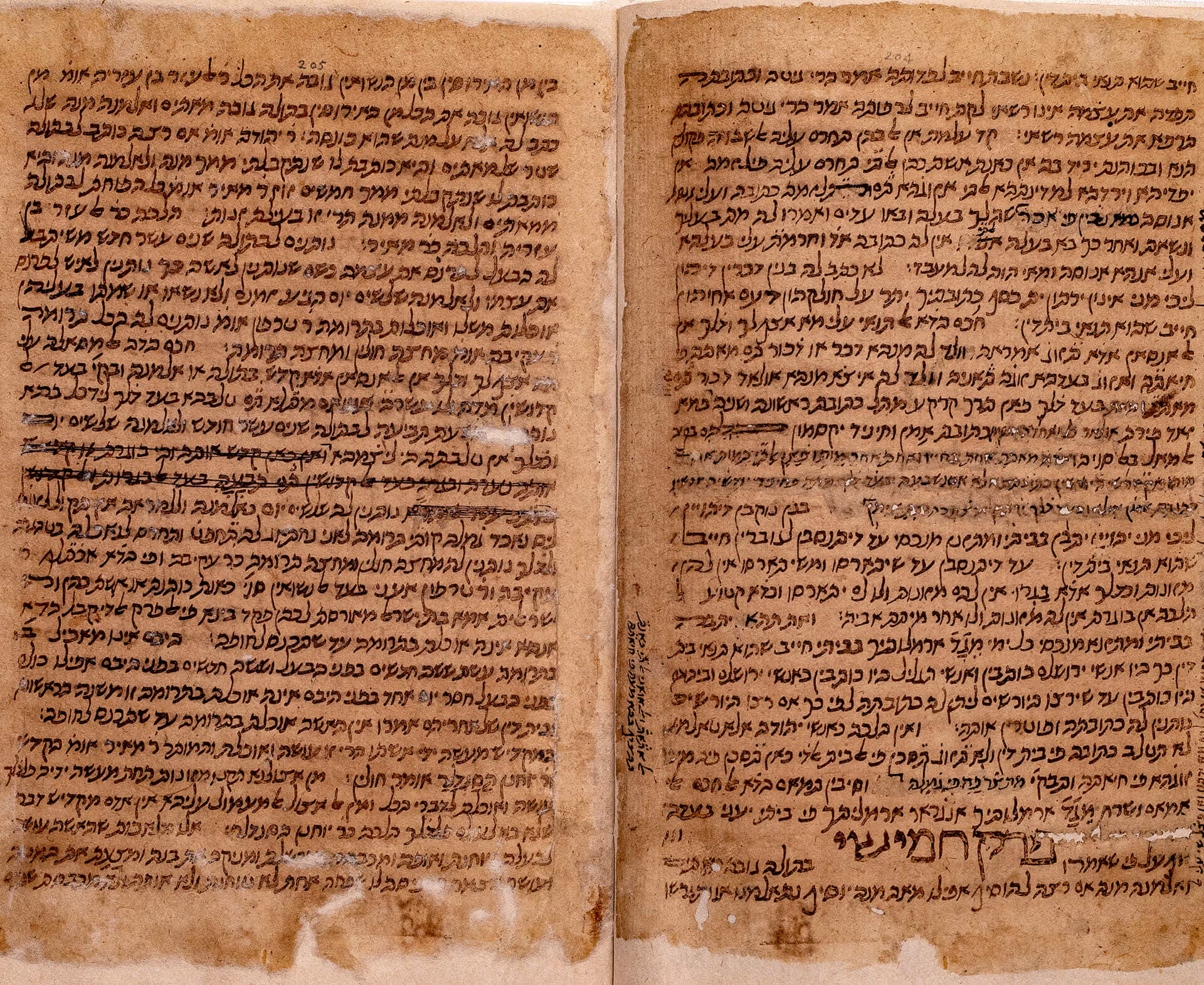

tab2img1=A two-page spread in the Vulgate

tab3img3=This illustration (apparently) depicts a Jerusalemite Jew handing over letters encouraging the Jews of Alexandria to celebrate Hanukkah. From the Vulgate, p. 426

.avif)

.svg)