If any song has the power to symbolize something as terrible as a war, then the song Lu Yehi, more than anything, has come to symbolize the Yom Kippur War. That is why it’s somewhat surprising to learn that this song was actually already in the works even before the war began. Naomi Shemer wanted to adapt John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s “Let It Be” to Hebrew, as reflected in the title, Lu Yehi, which is a direct translation.

During the first days of the war, Shemer wrote lyrics that expressed hope and prayers for the soldiers’ safe return home. At first, she used the melody of The Beatles’ original song but, influenced by her husband Mordechai Horowitz, Shemer decided to later compose an entirely new melody. “I won’t let you waste this song on a foreign tune. This is a Jewish war, and you should give it a Jewish tune,” he advised her.

If any song has the power to symbolize something as terrible as a war, then the song Lu Yehi, more than anything, has come to symbolize the Yom Kippur War. That is why it’s somewhat surprising to learn that this song was actually already in the works even before the war began. Naomi Shemer wanted to adapt John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s “Let It Be” to Hebrew, as reflected in the title, Lu Yehi, which is a direct translation.

During the first days of the war, Shemer wrote lyrics that expressed hope and prayers for the soldiers’ safe return home. At first, she used the melody of The Beatles’ original song but, influenced by her husband Mordechai Horowitz, Shemer decided to later compose an entirely new melody. “I won’t let you waste this song on a foreign tune. This is a Jewish war, and you should give it a Jewish tune,” he advised her.

If any song has the power to symbolize something as terrible as a war, then the song Lu Yehi, more than anything, has come to symbolize the Yom Kippur War. That is why it’s somewhat surprising to learn that this song was actually already in the works even before the war began. Naomi Shemer wanted to adapt John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s “Let It Be” to Hebrew, as reflected in the title, Lu Yehi, which is a direct translation.

During the first days of the war, Shemer wrote lyrics that expressed hope and prayers for the soldiers’ safe return home. At first, she used the melody of The Beatles’ original song but, influenced by her husband Mordechai Horowitz, Shemer decided to later compose an entirely new melody. “I won’t let you waste this song on a foreign tune. This is a Jewish war, and you should give it a Jewish tune,” he advised her.

And so, at the height of the war, Shemer composed an original melody and even sang the song on Israeli TV. This performance immediately made waves and took the people of Israel by storm. The song quickly spread to the soldiers as well, thanks to performances by Chava Alberstein and the HaGashash HaHiver trio.

And so, at the height of the war, Shemer composed an original melody and even sang the song on Israeli TV. This performance immediately made waves and took the people of Israel by storm. The song quickly spread to the soldiers as well, thanks to performances by Chava Alberstein and the HaGashash HaHiver trio.

And so, at the height of the war, Shemer composed an original melody and even sang the song on Israeli TV. This performance immediately made waves and took the people of Israel by storm. The song quickly spread to the soldiers as well, thanks to performances by Chava Alberstein and the HaGashash HaHiver trio.

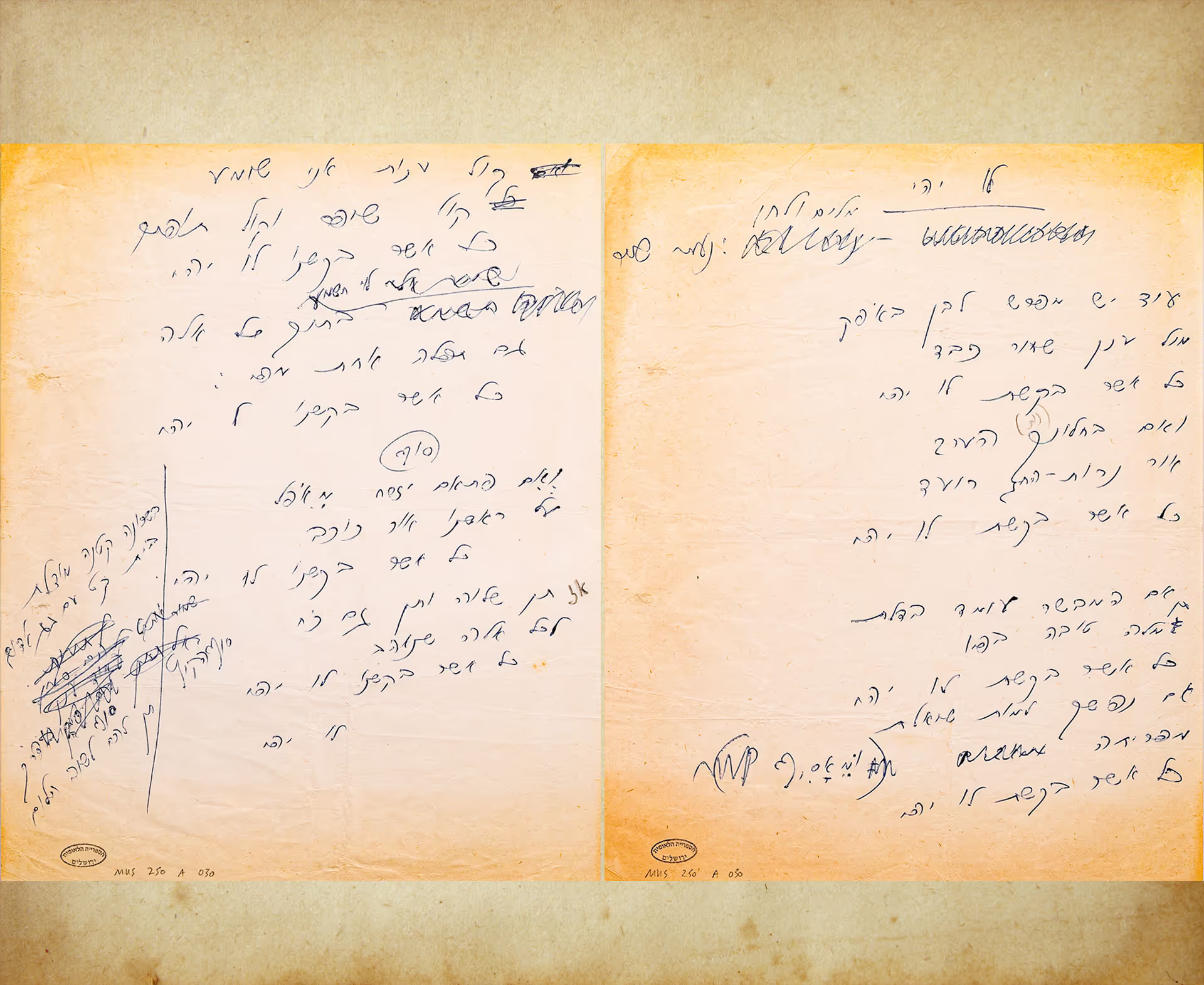

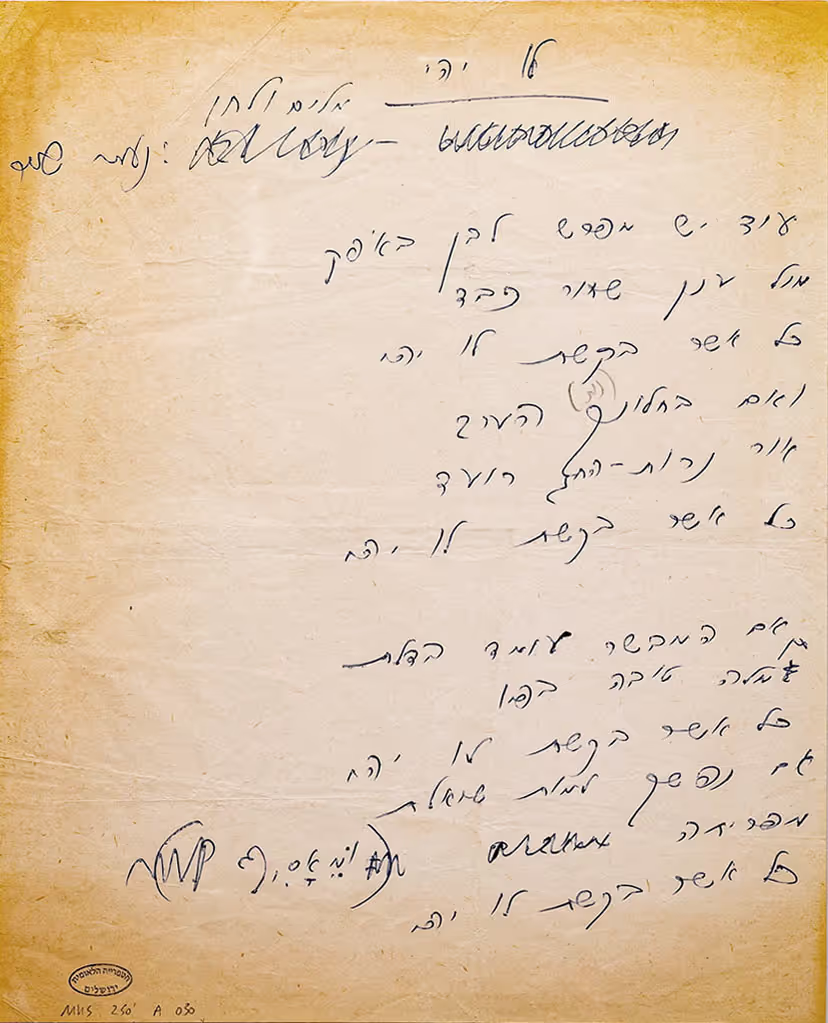

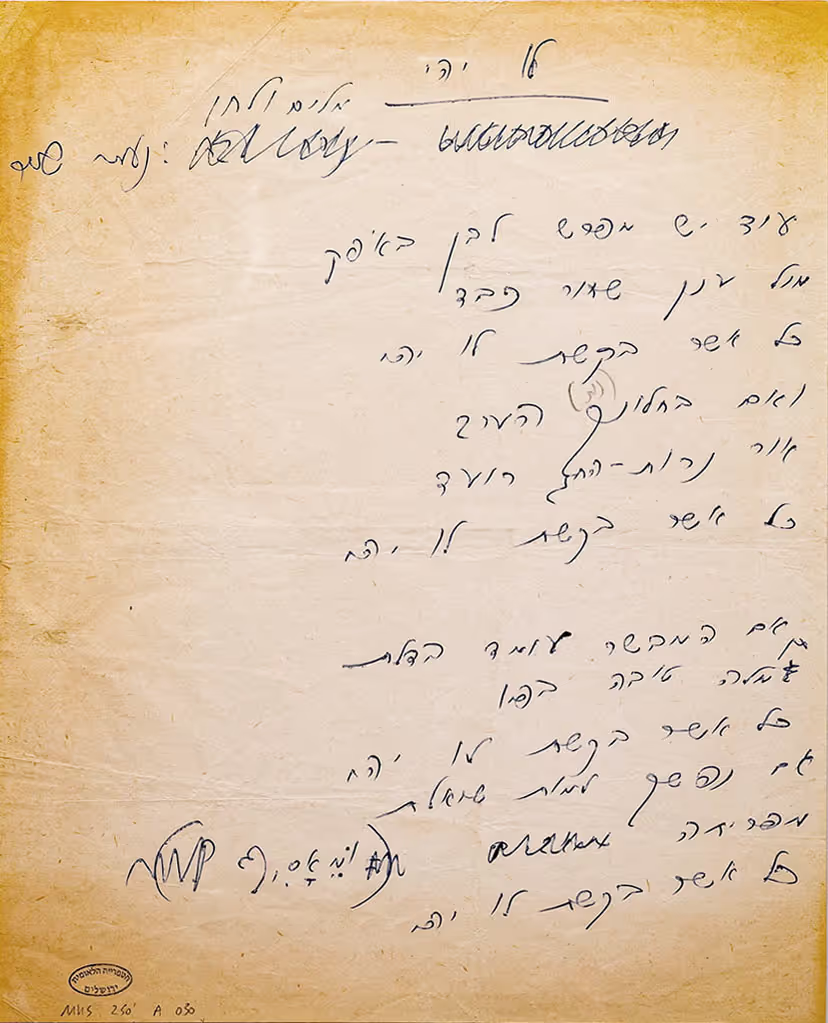

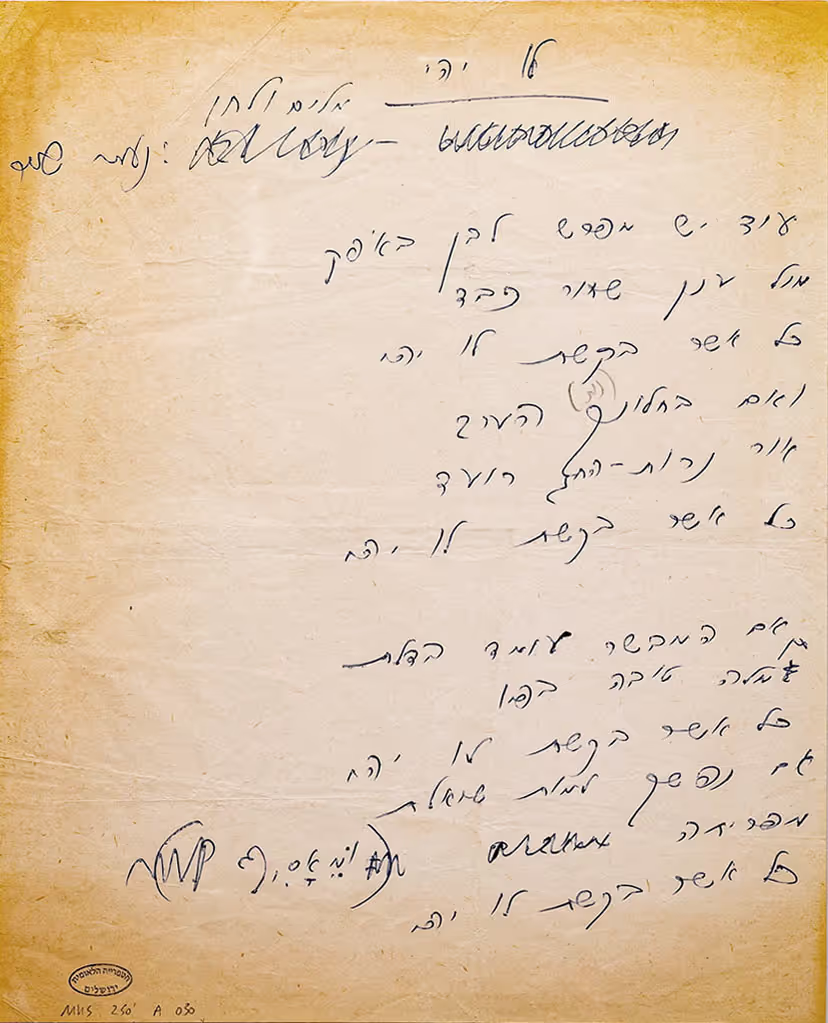

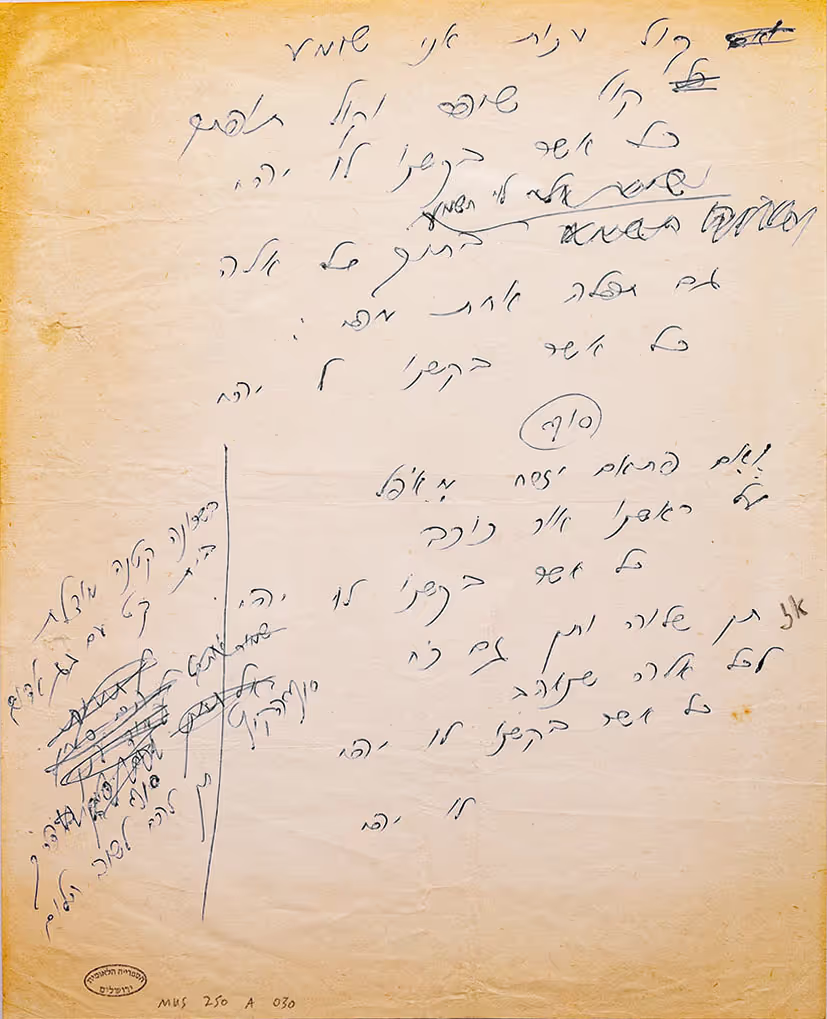

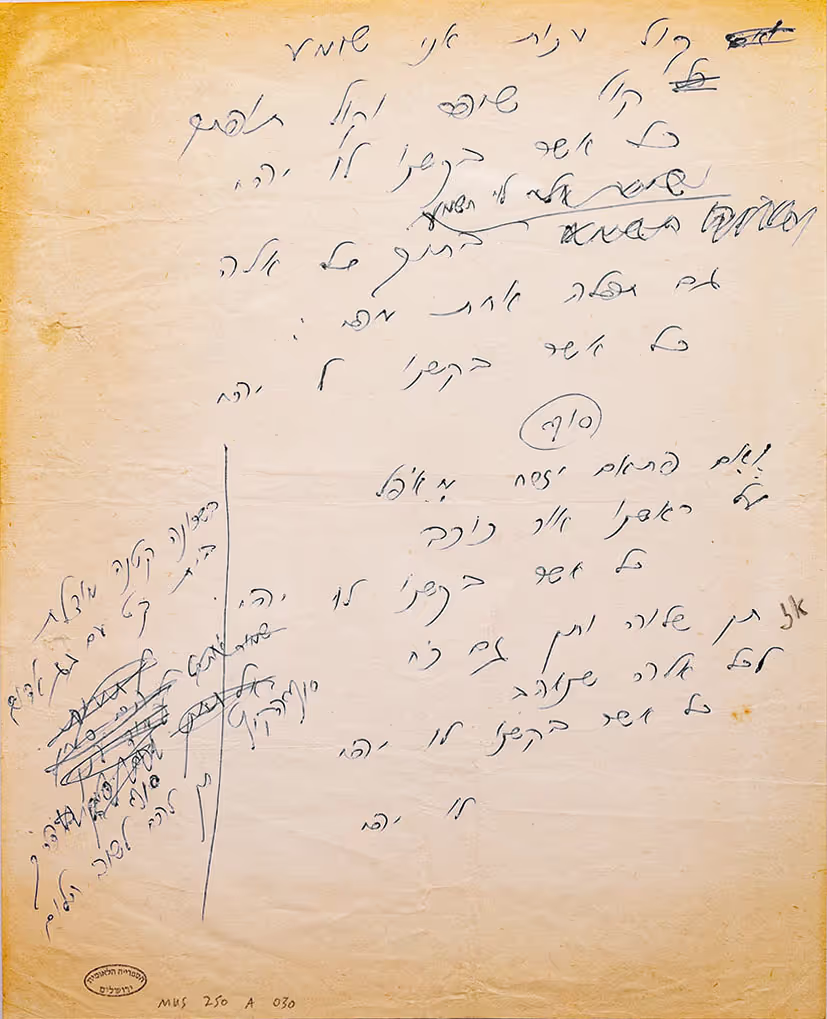

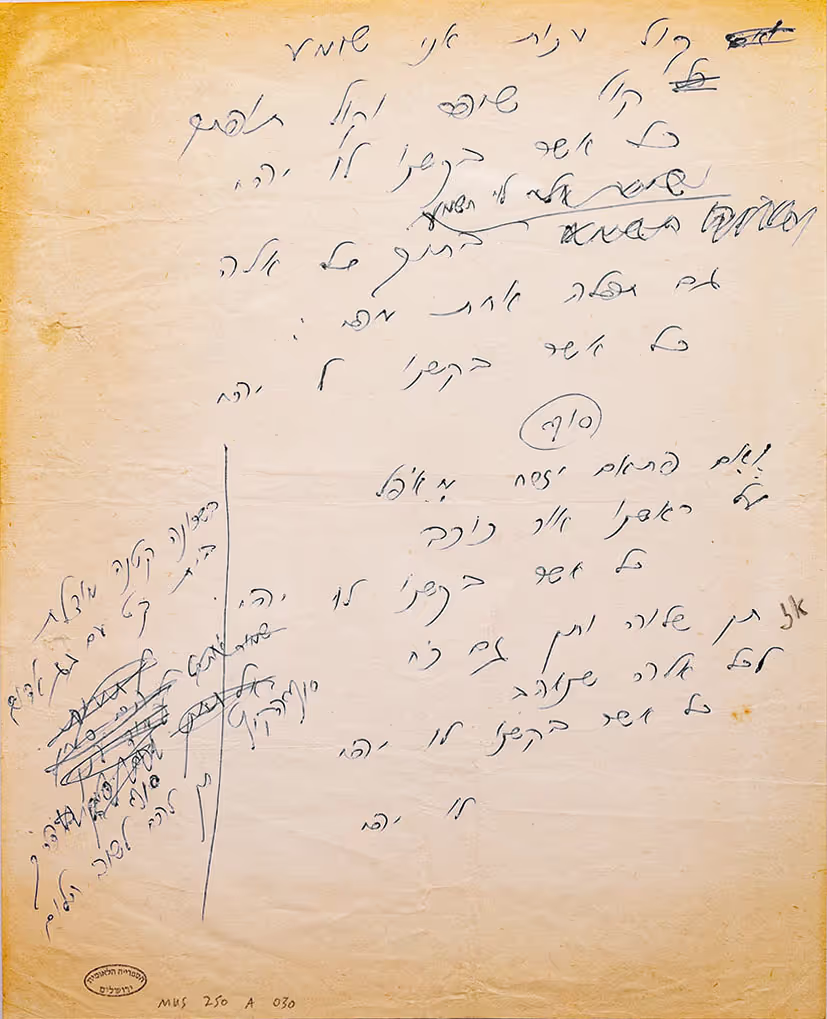

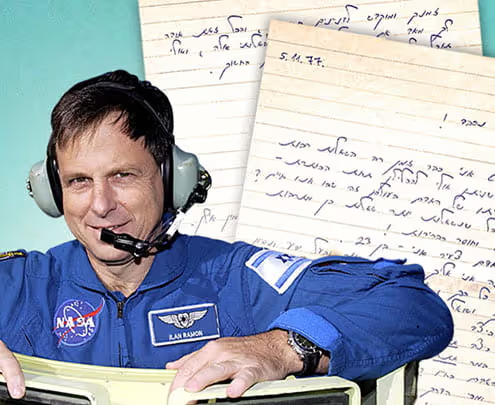

Shemer was quickly flooded with responses from the public. The song became something of a national prayer in Israel. The words and melody tugged hard at the heartstrings. Later, the National Library of Israel was endowed with Naomi Shemer’s personal archives, which included her handwritten lyrics to Lu Yehi as well as many letters she received from people of all walks of life. The letters express how Israelis were moved by the song and they include personal stories that show how Lu Yehi became a part of the Israeli cultural canon and a song that unified Israeli society during those particularly difficult days.

“A few weeks ago, we sat down as usual and spoke about them, about those who are not with us. Suddenly, in the background to this sad conversation, we heard your song and fell silent. We felt as if we had found the answer to what we were trying to express, let it be…let it be… and in fact, unashamed, we found ourselves shedding a tear…” Corporal Ilan Bachar wrote these words on behalf of soldiers from an armored corps reconnaissance unit toward the end of December 1973.

Two days after the ceasefire was announced, near the end of October, a soldier writes a letter to Shemer that states, “Naomi, it is hard to express in words how the heart feels about your song. ‘Let It Be’. Keep it up! Yours, An anonymous solder”

Shemer was quickly flooded with responses from the public. The song became something of a national prayer in Israel. The words and melody tugged hard at the heartstrings. Later, the National Library of Israel was endowed with Naomi Shemer’s personal archives, which included her handwritten lyrics to Lu Yehi as well as many letters she received from people of all walks of life. The letters express how Israelis were moved by the song and they include personal stories that show how Lu Yehi became a part of the Israeli cultural canon and a song that unified Israeli society during those particularly difficult days.

“A few weeks ago, we sat down as usual and spoke about them, about those who are not with us. Suddenly, in the background to this sad conversation, we heard your song and fell silent. We felt as if we had found the answer to what we were trying to express, let it be…let it be… and in fact, unashamed, we found ourselves shedding a tear…” Corporal Ilan Bachar wrote these words on behalf of soldiers from an armored corps reconnaissance unit toward the end of December 1973.

Two days after the ceasefire was announced, near the end of October, a soldier writes a letter to Shemer that states, “Naomi, it is hard to express in words how the heart feels about your song. ‘Let It Be’. Keep it up! Yours, An anonymous solder”

Shemer was quickly flooded with responses from the public. The song became something of a national prayer in Israel. The words and melody tugged hard at the heartstrings. Later, the National Library of Israel was endowed with Naomi Shemer’s personal archives, which included her handwritten lyrics to Lu Yehi as well as many letters she received from people of all walks of life. The letters express how Israelis were moved by the song and they include personal stories that show how Lu Yehi became a part of the Israeli cultural canon and a song that unified Israeli society during those particularly difficult days.

“A few weeks ago, we sat down as usual and spoke about them, about those who are not with us. Suddenly, in the background to this sad conversation, we heard your song and fell silent. We felt as if we had found the answer to what we were trying to express, let it be…let it be… and in fact, unashamed, we found ourselves shedding a tear…” Corporal Ilan Bachar wrote these words on behalf of soldiers from an armored corps reconnaissance unit toward the end of December 1973.

Two days after the ceasefire was announced, near the end of October, a soldier writes a letter to Shemer that states, “Naomi, it is hard to express in words how the heart feels about your song. ‘Let It Be’. Keep it up! Yours, An anonymous solder”

It wasn’t only soldiers who drew encouragement from this moving song. A representative of the Senesh family from Haifa wrote Shemer a touching letter in December that same year. He wrote to her that the song’s lyrics, “helped me get through the hardest thing I’d ever been through, the uncertainty. Until we got word that our son was being held in Egyptian captivity…this song of yours was like a prayer for me, a kind of prayer that helps a man of faith and calms him.”

On October 19, as the war was still being waged, Shiona Ravitzky wrote to Shemer about how moved the teachers and students were as soon as she brought Lu Yehi to the school where she taught. “We sing it like a prayer,” she proudly wrote.

It wasn’t only soldiers who drew encouragement from this moving song. A representative of the Senesh family from Haifa wrote Shemer a touching letter in December that same year. He wrote to her that the song’s lyrics, “helped me get through the hardest thing I’d ever been through, the uncertainty. Until we got word that our son was being held in Egyptian captivity…this song of yours was like a prayer for me, a kind of prayer that helps a man of faith and calms him.”

On October 19, as the war was still being waged, Shiona Ravitzky wrote to Shemer about how moved the teachers and students were as soon as she brought Lu Yehi to the school where she taught. “We sing it like a prayer,” she proudly wrote.

It wasn’t only soldiers who drew encouragement from this moving song. A representative of the Senesh family from Haifa wrote Shemer a touching letter in December that same year. He wrote to her that the song’s lyrics, “helped me get through the hardest thing I’d ever been through, the uncertainty. Until we got word that our son was being held in Egyptian captivity…this song of yours was like a prayer for me, a kind of prayer that helps a man of faith and calms him.”

On October 19, as the war was still being waged, Shiona Ravitzky wrote to Shemer about how moved the teachers and students were as soon as she brought Lu Yehi to the school where she taught. “We sing it like a prayer,” she proudly wrote.

In December 1973, Bracha Vardi, who lost her husband in the war, wrote to Shemer and told her that her eldest son now sang the song, which had "acquired a double meaning”. Vardi added: “In reading through a letter I wrote to my husband before I knew of his passing, I found that I had copied your song for him so that he too would know your prayer – our prayer, the prayer of the entire nation and the children. The letter was returned to me, as were all the other letters I sent to him, aside from one that managed to reach him, and our prayer - was lost in space.”

In December 1973, Bracha Vardi, who lost her husband in the war, wrote to Shemer and told her that her eldest son now sang the song, which had "acquired a double meaning”. Vardi added: “In reading through a letter I wrote to my husband before I knew of his passing, I found that I had copied your song for him so that he too would know your prayer – our prayer, the prayer of the entire nation and the children. The letter was returned to me, as were all the other letters I sent to him, aside from one that managed to reach him, and our prayer - was lost in space.”

In December 1973, Bracha Vardi, who lost her husband in the war, wrote to Shemer and told her that her eldest son now sang the song, which had "acquired a double meaning”. Vardi added: “In reading through a letter I wrote to my husband before I knew of his passing, I found that I had copied your song for him so that he too would know your prayer – our prayer, the prayer of the entire nation and the children. The letter was returned to me, as were all the other letters I sent to him, aside from one that managed to reach him, and our prayer - was lost in space.”

tab2img3=The lyrics to Lu Yehi in Naomi Shemer’s handwriting

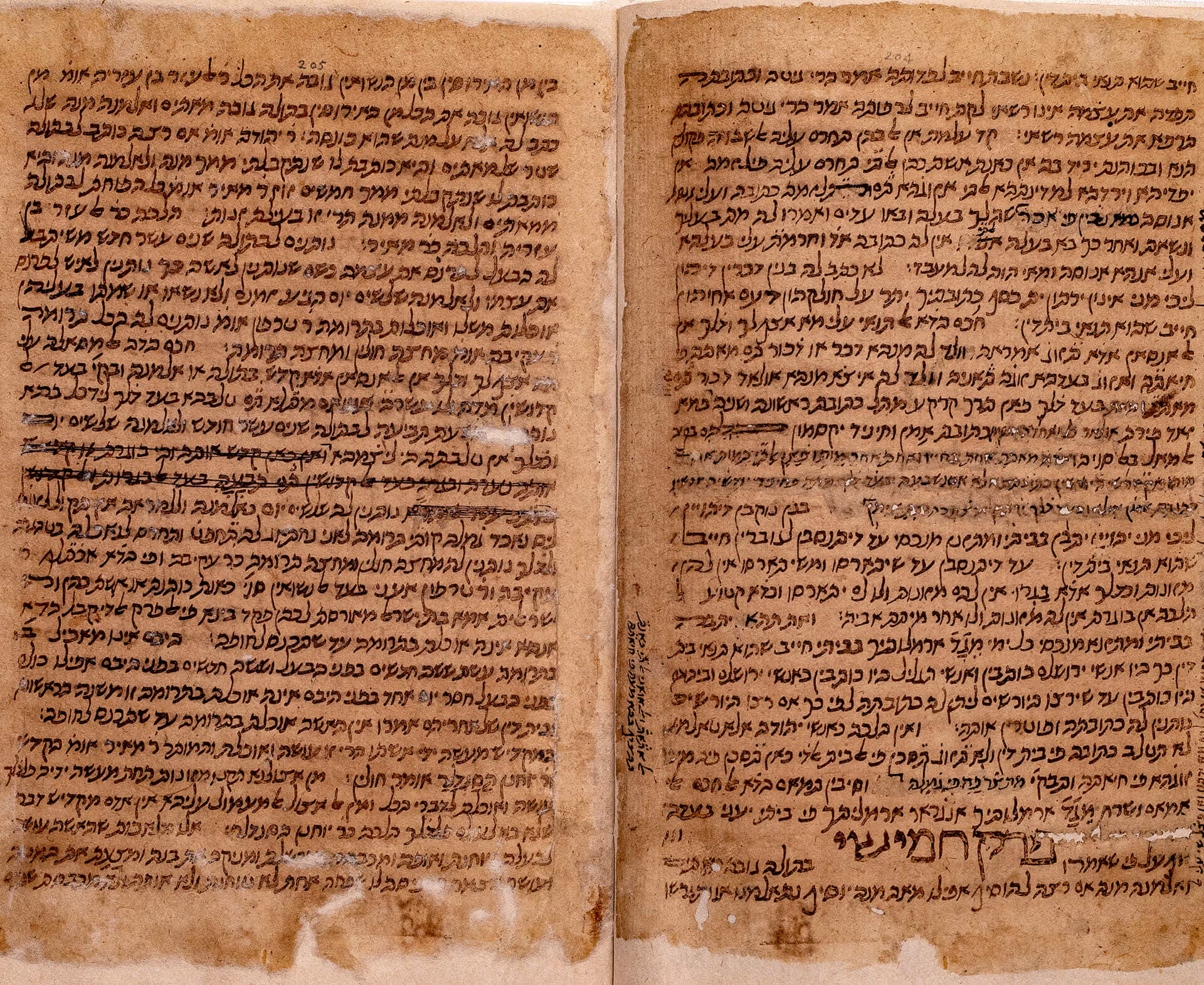

tab3img2=“We found ourselves shedding a tear.” From a letter by Corporal Ilan Bachar to Naomi Shemer

tab3img3=“It is hard to express in words how the heart feels about your song.” A letter sent from an anonymous soldier to Naomi Shemer

tab4img2=“These words banished all the nightmares from my mind.” A letter from the family of a soldier who was taken captive in Egypt

tab4img3=“The children really enjoy singing the song.” Teacher Shiona Ravitzky in a letter to Naomi Shemer

tab5img2=“And our prayer – was lost in space.” A letter written to Naomi Shemer by a war widow

.avif)

.svg)