At the beginning of the 16th century, Venice became a major center for the early printing industry. Jews, however, were not allowed to own printing houses. Non-Jewish printing houses published Hebrew and Jewish works, hoping to make a profit by selling to Jewish customers. The renaissance culture of the period also encouraged Christian readers to return to ancient texts and sources - including works in Hebrew – and thus a market for texts printed in Hebrew emerged.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Venice became a major center for the early printing industry. Jews, however, were not allowed to own printing houses. Non-Jewish printing houses published Hebrew and Jewish works, hoping to make a profit by selling to Jewish customers. The renaissance culture of the period also encouraged Christian readers to return to ancient texts and sources - including works in Hebrew – and thus a market for texts printed in Hebrew emerged.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Venice became a major center for the early printing industry. Jews, however, were not allowed to own printing houses. Non-Jewish printing houses published Hebrew and Jewish works, hoping to make a profit by selling to Jewish customers. The renaissance culture of the period also encouraged Christian readers to return to ancient texts and sources - including works in Hebrew – and thus a market for texts printed in Hebrew emerged.

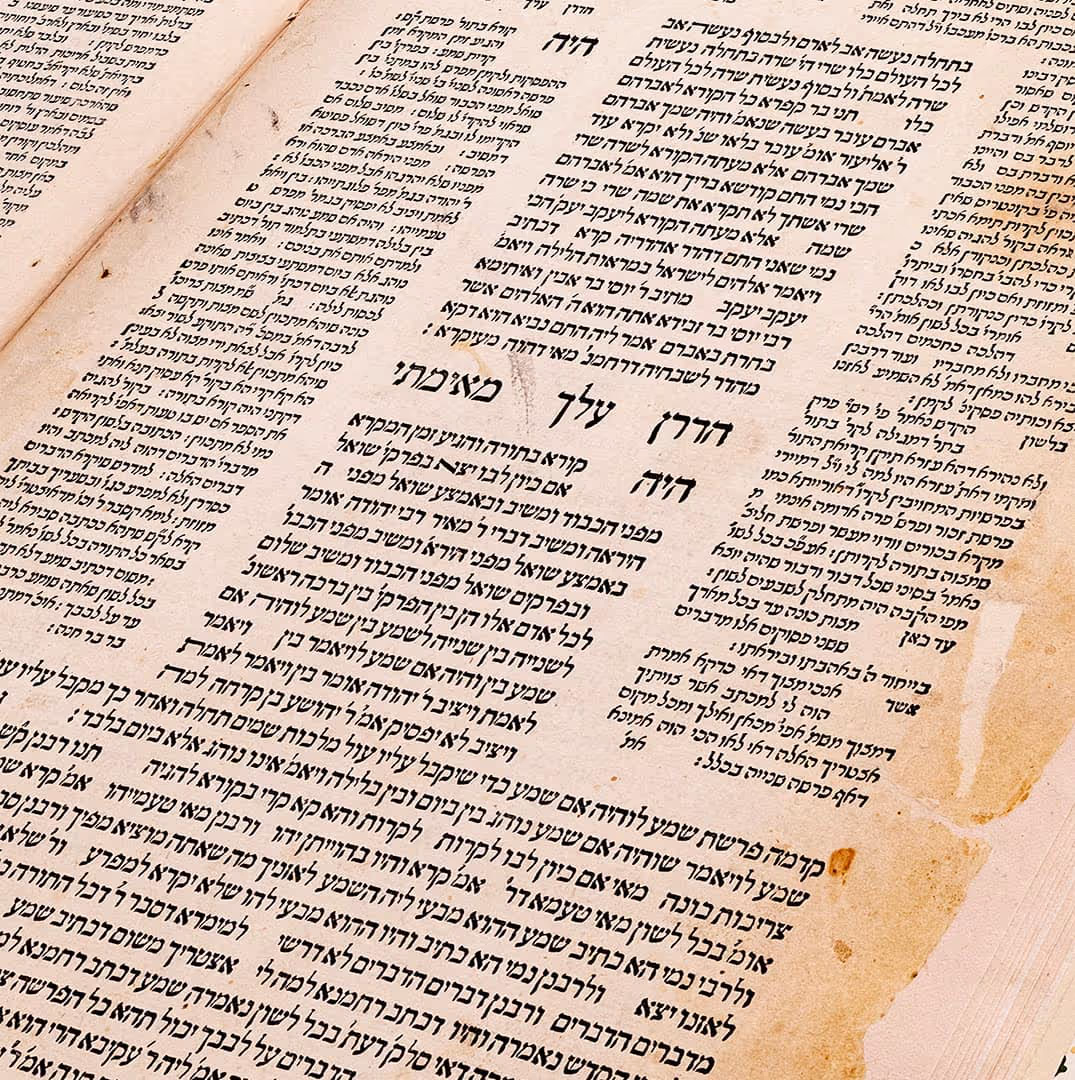

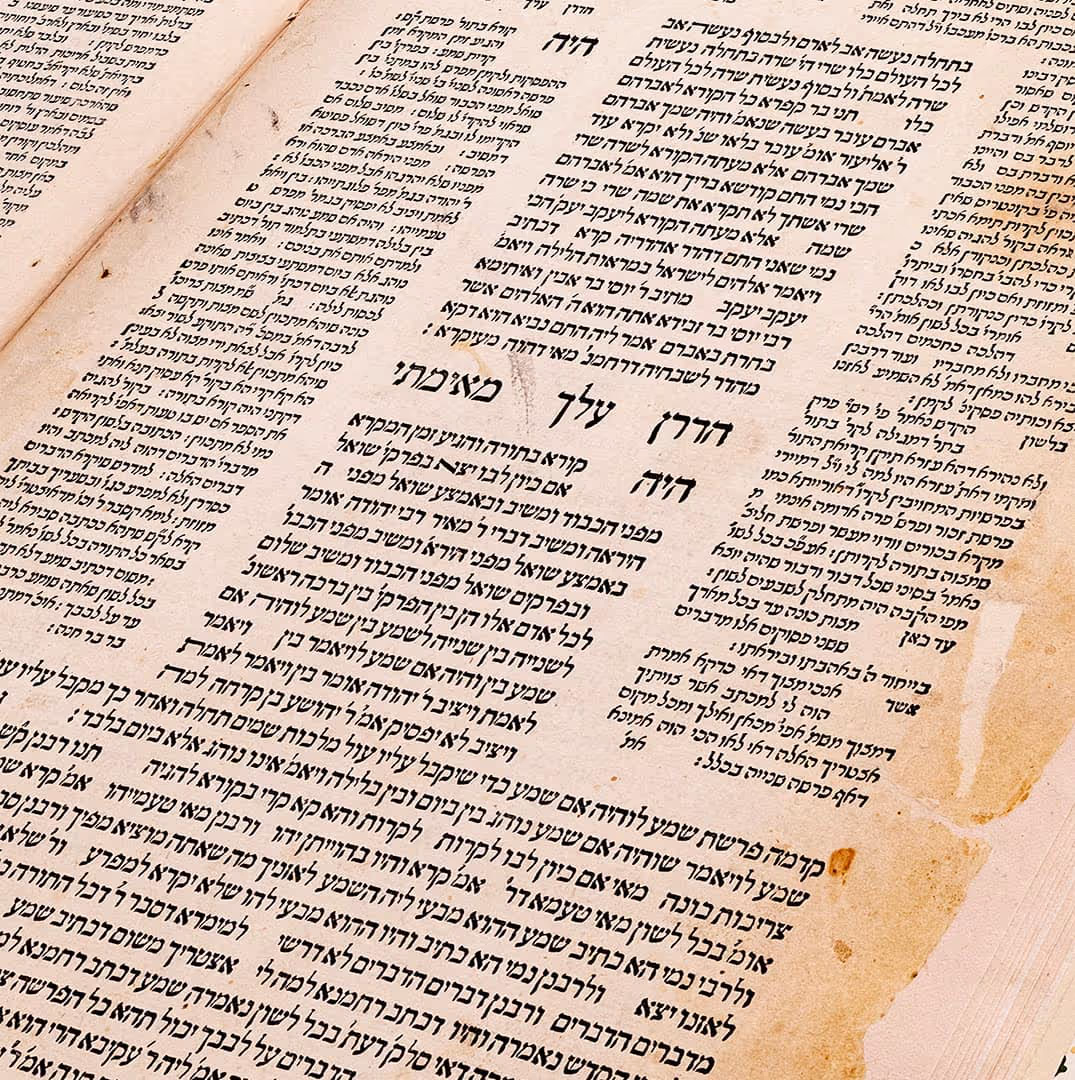

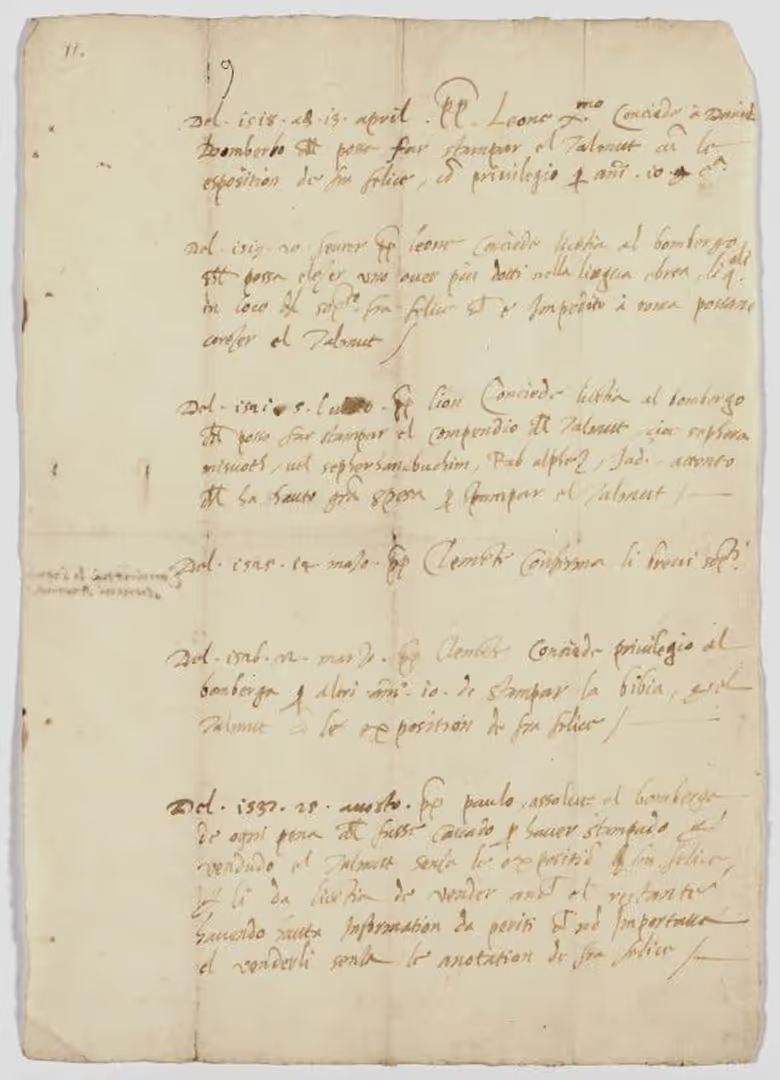

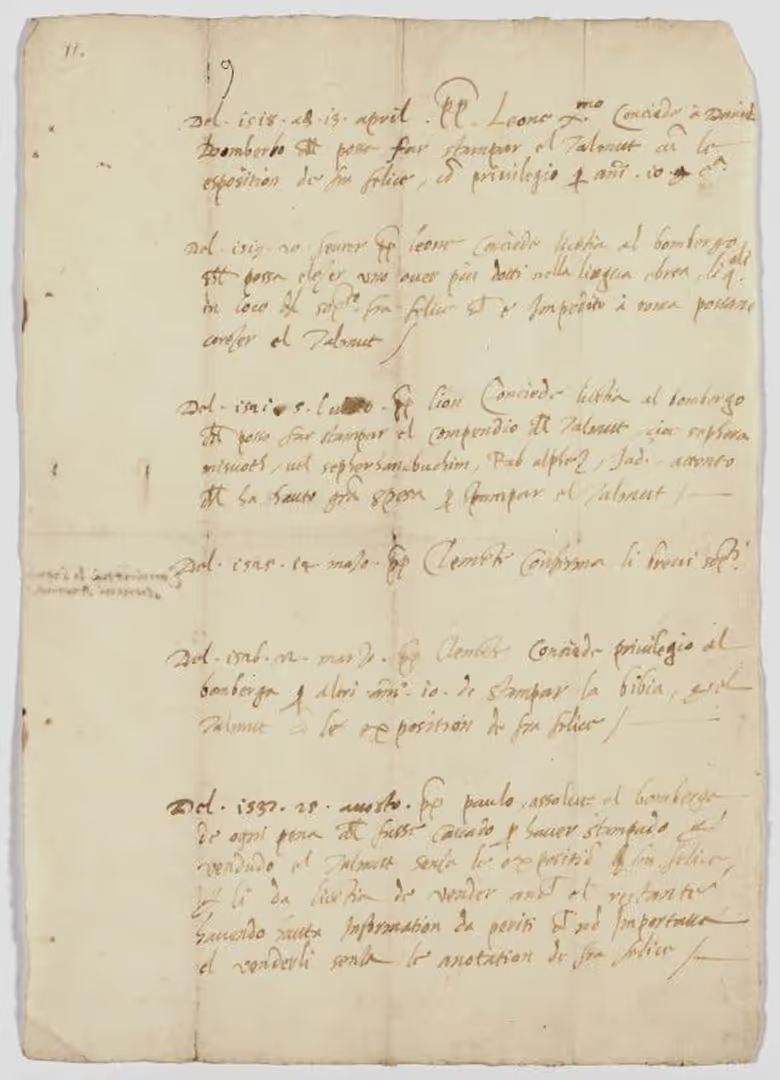

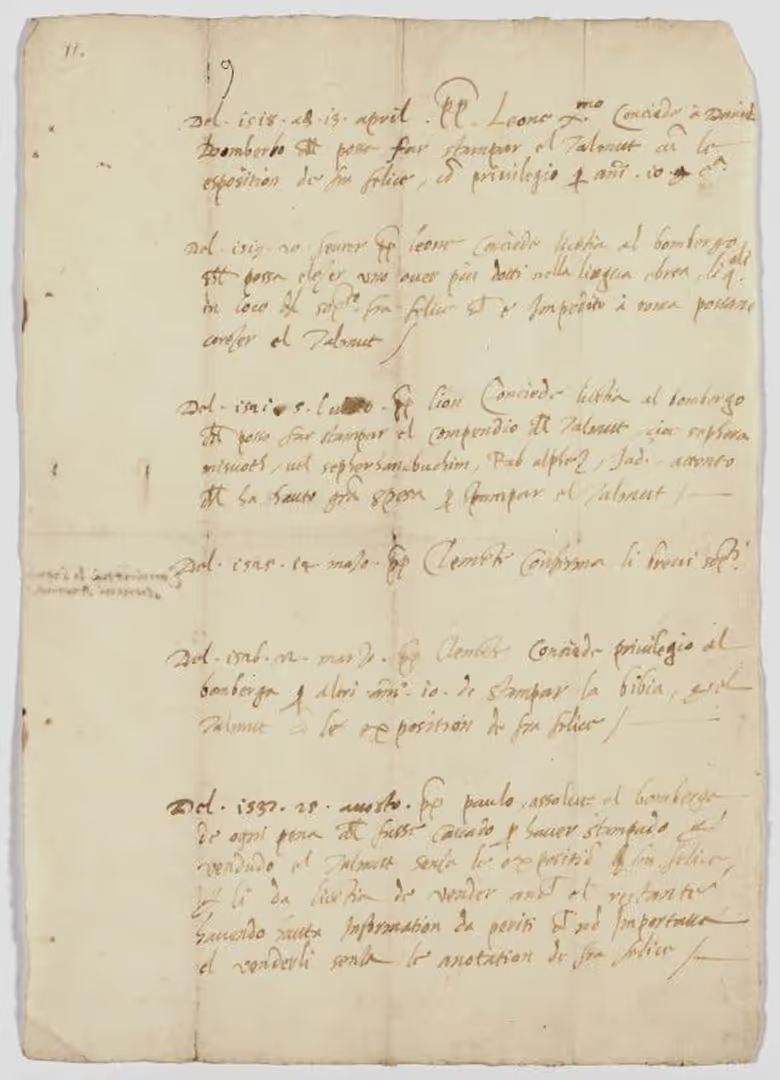

A document from the René Braginsky Collection tells the story behind the first printed edition of the complete Talmud, the Bomberg Talmud (1520-1523).

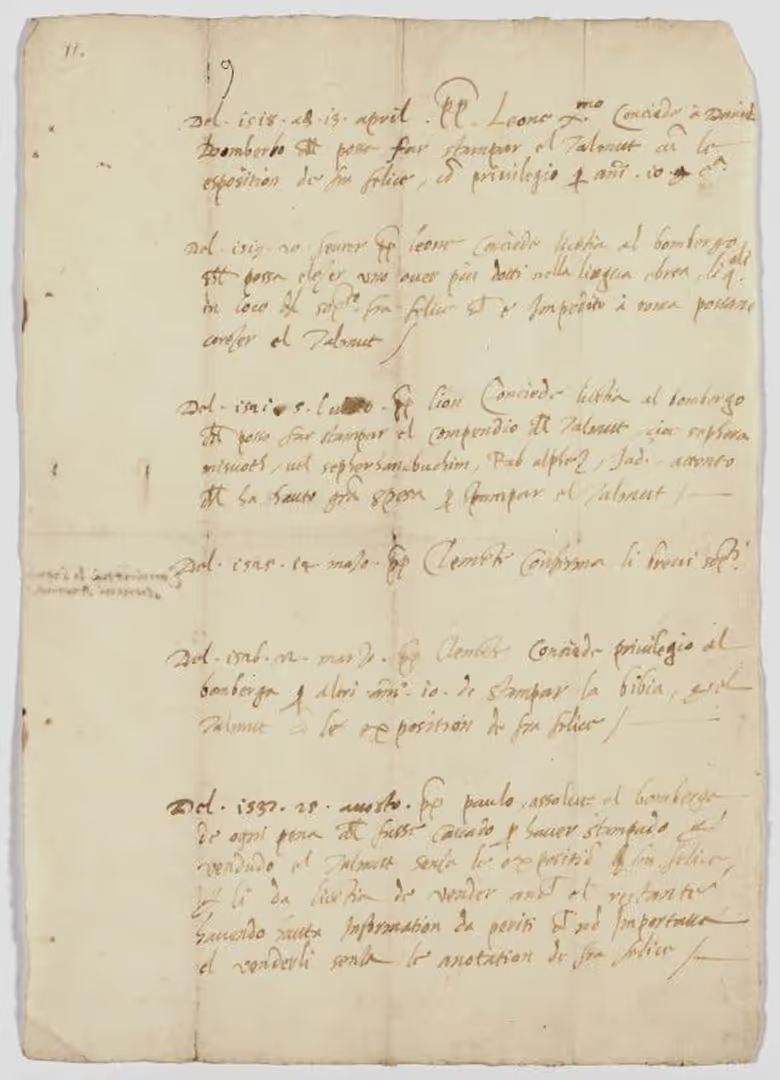

The document demonstrates that on April 13, 1518, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian printer, received the exclusive printing rights, along with an endorsement from Pope Leo X, to print this first edition of the Talmud in Venice.

There was, however, a catch. Bomberg was handed this privilege on the condition that the edition would be accompanied by the polemic work of the Jewish convert to Christianity, Felix Pratensis. Pratensis' work was aimed at refuting content opposed to the Christian faith, which appears in the Talmud.

A document from the René Braginsky Collection tells the story behind the first printed edition of the complete Talmud, the Bomberg Talmud (1520-1523).

The document demonstrates that on April 13, 1518, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian printer, received the exclusive printing rights, along with an endorsement from Pope Leo X, to print this first edition of the Talmud in Venice.

There was, however, a catch. Bomberg was handed this privilege on the condition that the edition would be accompanied by the polemic work of the Jewish convert to Christianity, Felix Pratensis. Pratensis' work was aimed at refuting content opposed to the Christian faith, which appears in the Talmud.

A document from the René Braginsky Collection tells the story behind the first printed edition of the complete Talmud, the Bomberg Talmud (1520-1523).

The document demonstrates that on April 13, 1518, Daniel Bomberg, a Christian printer, received the exclusive printing rights, along with an endorsement from Pope Leo X, to print this first edition of the Talmud in Venice.

There was, however, a catch. Bomberg was handed this privilege on the condition that the edition would be accompanied by the polemic work of the Jewish convert to Christianity, Felix Pratensis. Pratensis' work was aimed at refuting content opposed to the Christian faith, which appears in the Talmud.

Historical evidence, or the lack thereof, makes it difficult to trace Bomberg’s actions following this demand, but it is obvious that the experienced printer understood the consequences of pairing a Christian-apologist treatise with the Talmud would alienate potential buyers. It is likely that Bomberg asked his friend and Hebrew teacher, that very same convert, Felix Pratensis, to beg the Pope to cancel the condition.

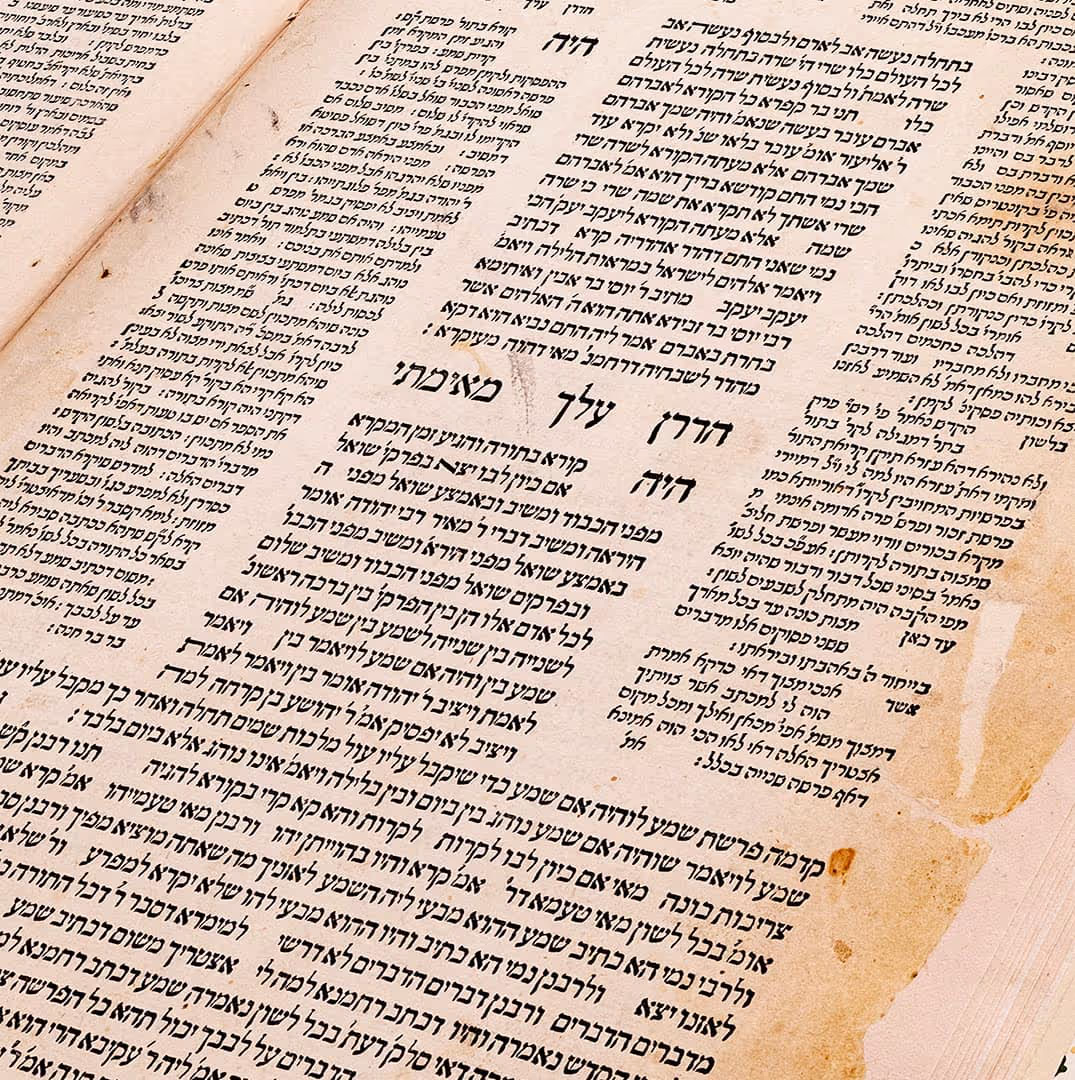

In a renewed license dated February 20, 1519, the Pope removed the requirement that the treatise be included, and instead Leo X allowed Bomberg to assign Christian Hebrew-readers to make certain amendments to the Talmud’s text.

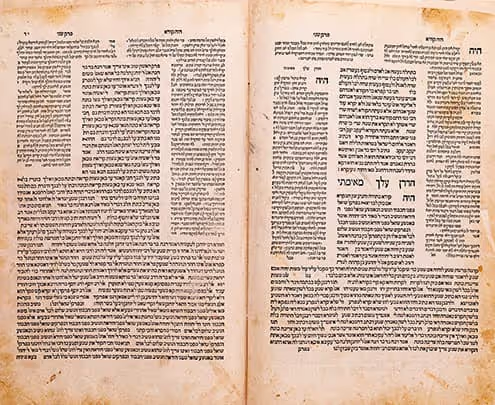

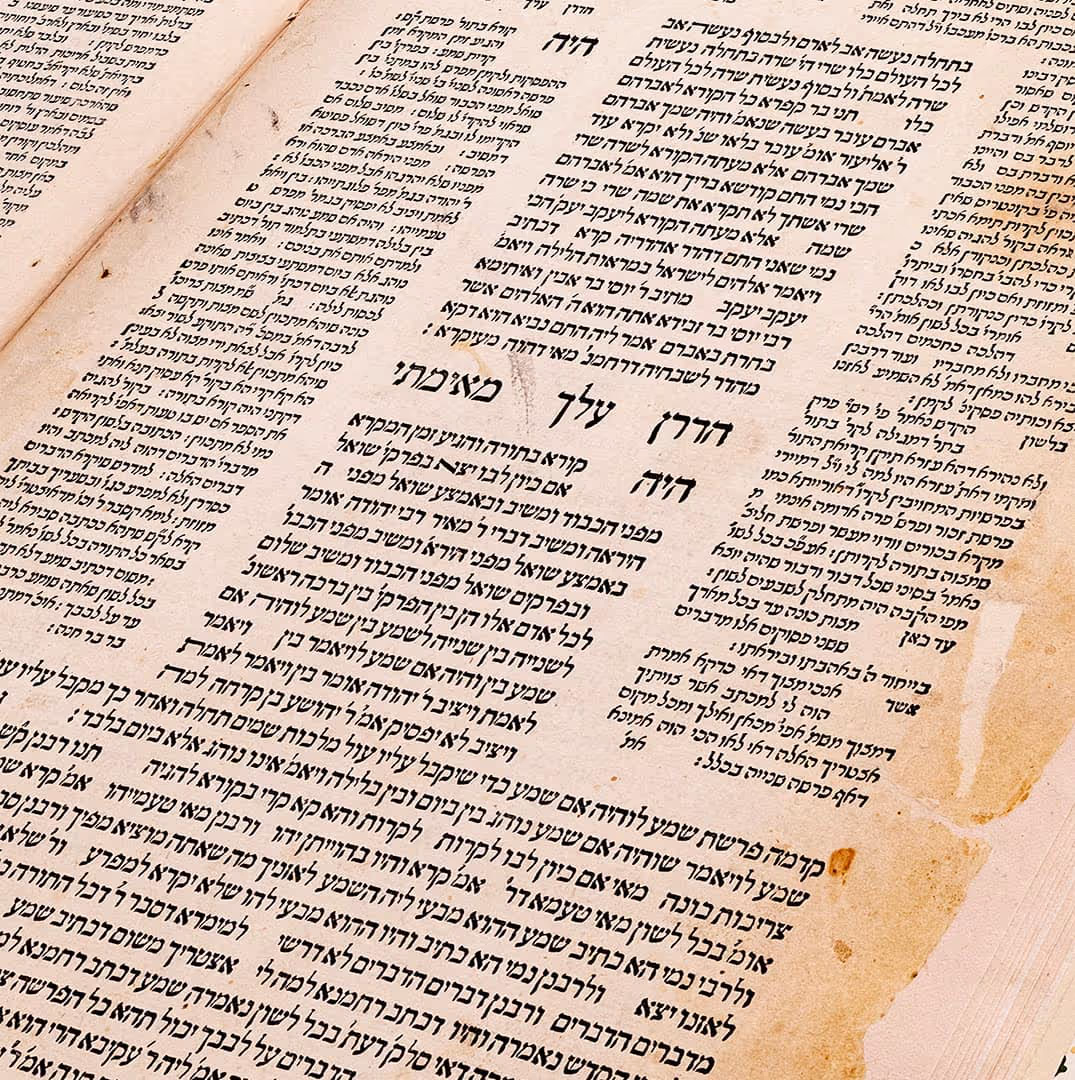

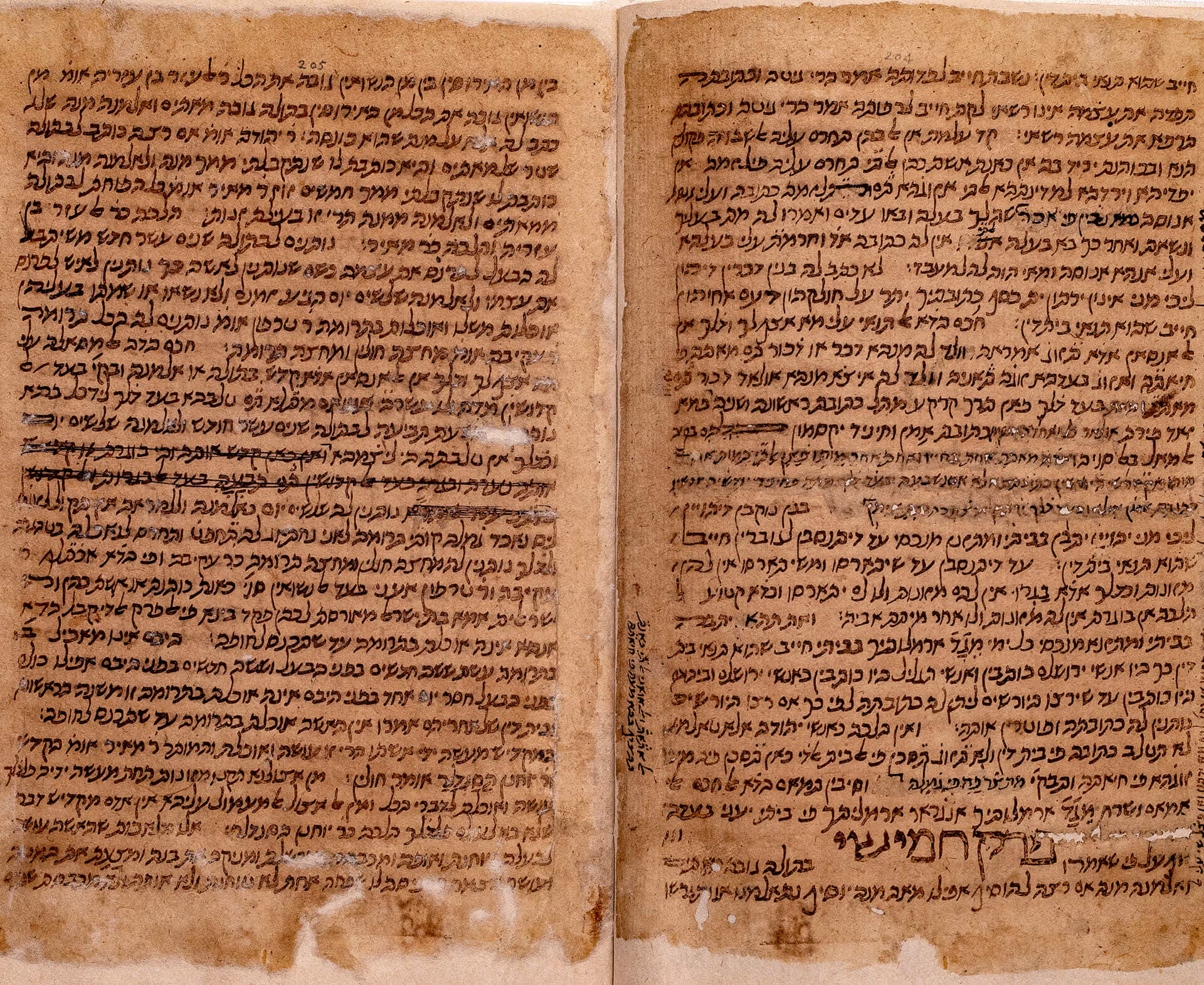

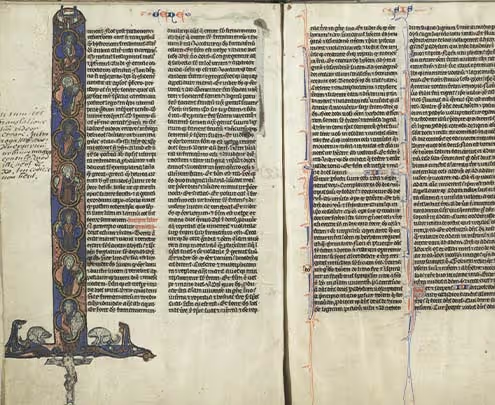

This saga would likely not have gotten any attention were it not for the fact that the Bomberg Talmud became a best-seller and took the Jewish world by storm. After the publication of this edition, the following printings of the Talmud consistently copied the Bomberg edition’s pagination and layout: the Talmudic text in the center, surrounded by Rashi’s commentary on the inside and that of the Tosafists on the outside.

Historical evidence, or the lack thereof, makes it difficult to trace Bomberg’s actions following this demand, but it is obvious that the experienced printer understood the consequences of pairing a Christian-apologist treatise with the Talmud would alienate potential buyers. It is likely that Bomberg asked his friend and Hebrew teacher, that very same convert, Felix Pratensis, to beg the Pope to cancel the condition.

In a renewed license dated February 20, 1519, the Pope removed the requirement that the treatise be included, and instead Leo X allowed Bomberg to assign Christian Hebrew-readers to make certain amendments to the Talmud’s text.

This saga would likely not have gotten any attention were it not for the fact that the Bomberg Talmud became a best-seller and took the Jewish world by storm. After the publication of this edition, the following printings of the Talmud consistently copied the Bomberg edition’s pagination and layout: the Talmudic text in the center, surrounded by Rashi’s commentary on the inside and that of the Tosafists on the outside.

Historical evidence, or the lack thereof, makes it difficult to trace Bomberg’s actions following this demand, but it is obvious that the experienced printer understood the consequences of pairing a Christian-apologist treatise with the Talmud would alienate potential buyers. It is likely that Bomberg asked his friend and Hebrew teacher, that very same convert, Felix Pratensis, to beg the Pope to cancel the condition.

In a renewed license dated February 20, 1519, the Pope removed the requirement that the treatise be included, and instead Leo X allowed Bomberg to assign Christian Hebrew-readers to make certain amendments to the Talmud’s text.

This saga would likely not have gotten any attention were it not for the fact that the Bomberg Talmud became a best-seller and took the Jewish world by storm. After the publication of this edition, the following printings of the Talmud consistently copied the Bomberg edition’s pagination and layout: the Talmudic text in the center, surrounded by Rashi’s commentary on the inside and that of the Tosafists on the outside.

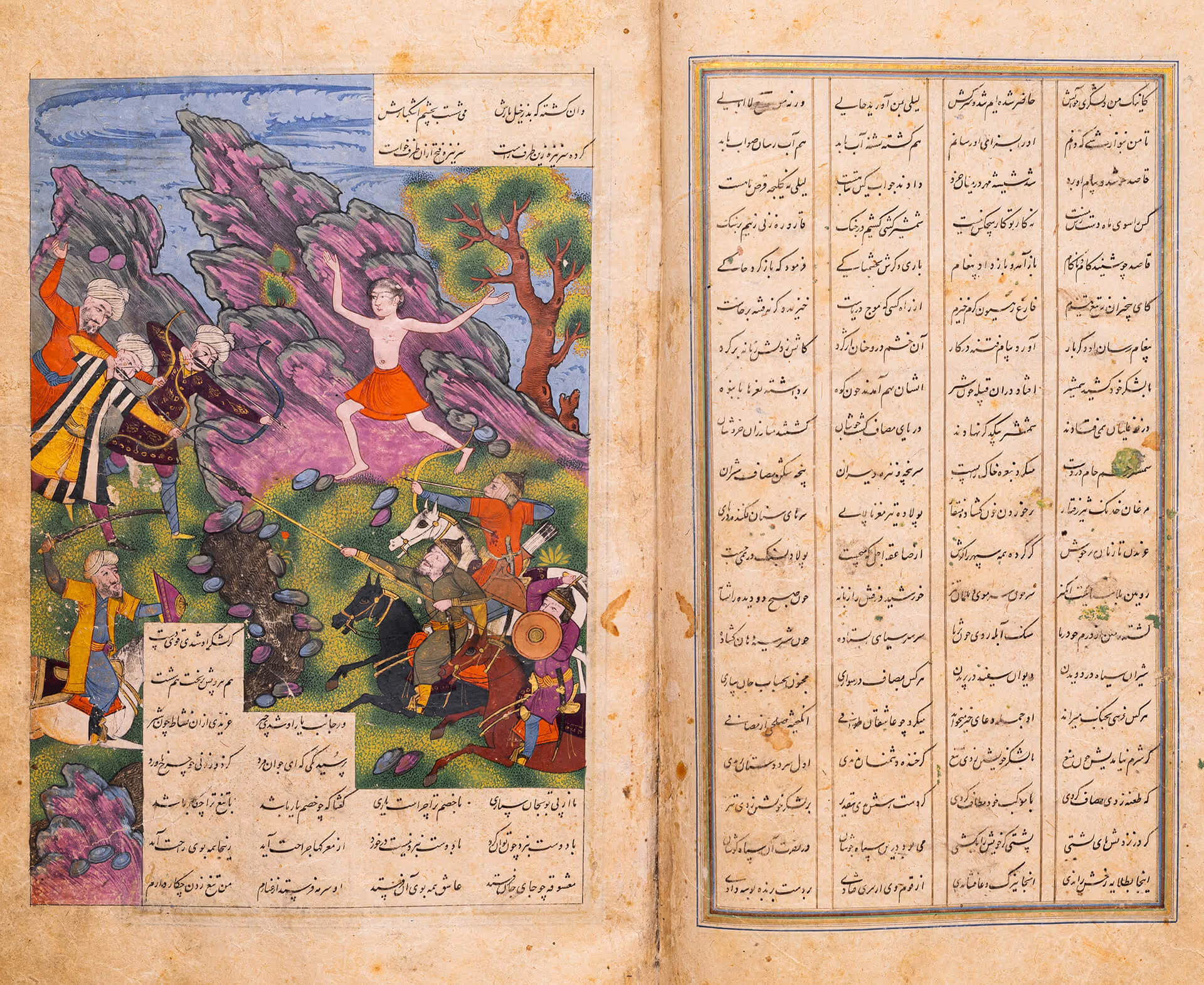

tab1img1=The Bomberg Talmud: Printed With the Pope's Approval

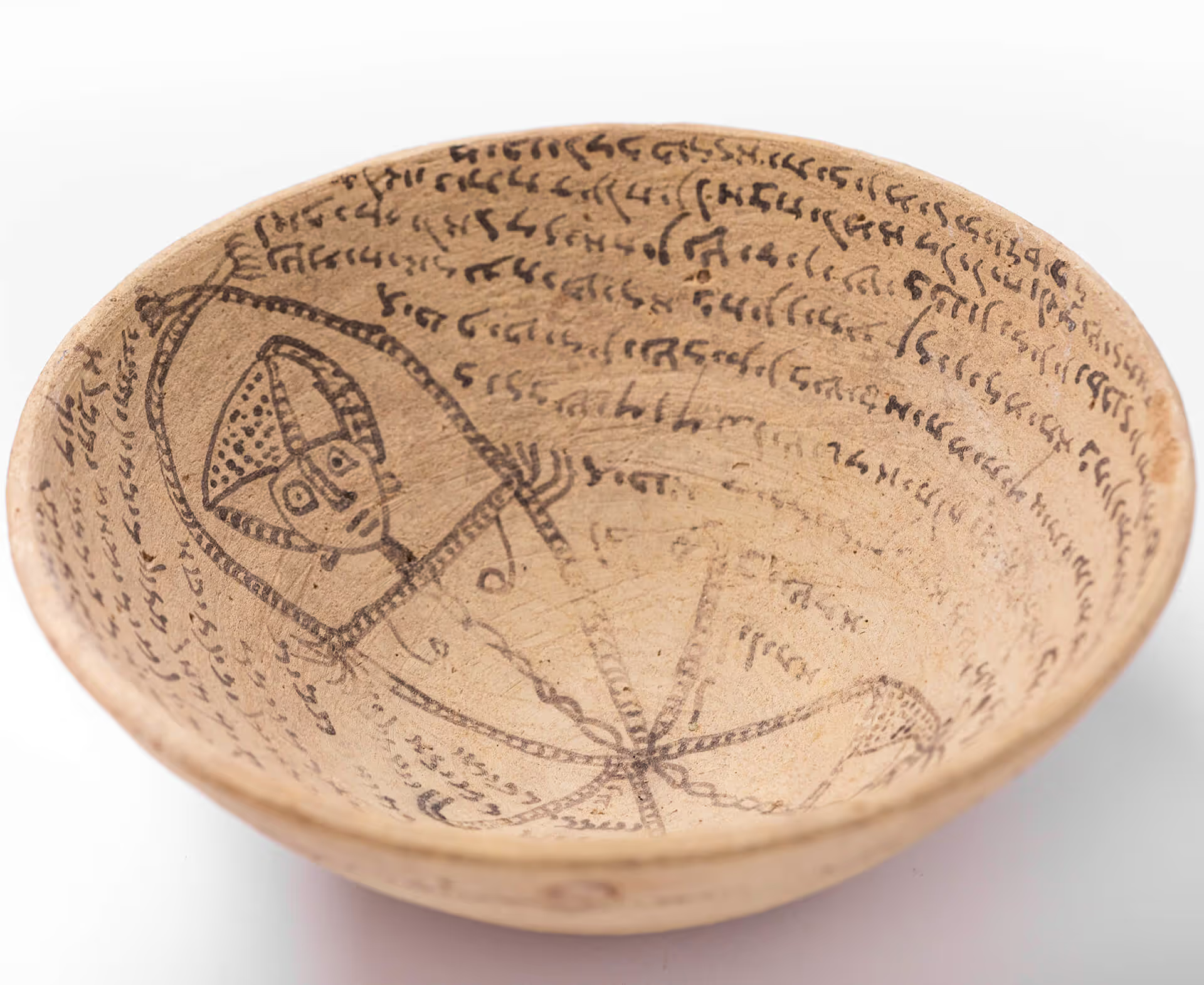

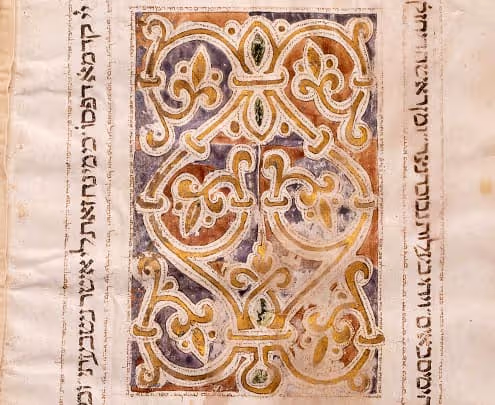

tab2img2=A 16th century Venetian document discussing rights and privileges for printing rabbinic literature, René Braginsky Collection, Zurich, BCB 283, photo: Ardon Bar-Hama

tab3img3=Portrait of Leo X, by Raphael

.avif)

.svg)